A world at war, 80 years ago — Commemorating local service

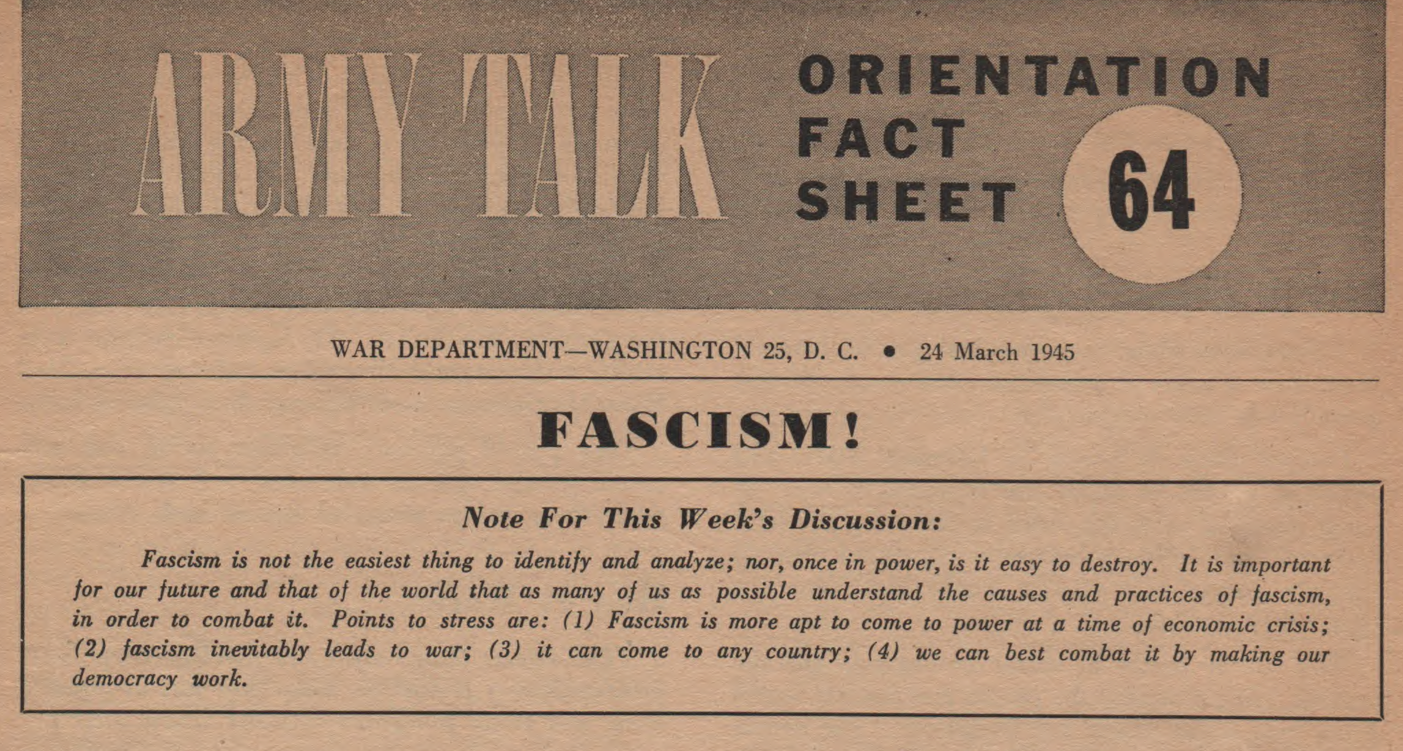

During the Spring of 1945 — 80 years ago — as the Allies closed in on victory, U.S. military leadership released an edition of Army Talk, Orientation Fact Sheet 64, with the simple title, “Fascism!” The pamphlet was part of a series created by the army during World War II to educate and inform soldiers, offering discussion topics, current events, and morale-boosting essays; it was printed and distributed in the field through Army units and designed to spark conversation and critical thinking among troops. The March 1945 edition of Army Talk was intended to remind soldiers what they were fighting against in plain terms. It described fascism as “the antithesis of democracy,” a system that thrived on “lies, oppression, and violence.” It urged soldiers to recognize that defeating fascism was not just about winning battles — it was about defending the core principles of truth, freedom, and justice.

But in addition to remembering what the fight was about, understanding more about the local people who sacrificed so much during WWII helps us understand that fascism was not an abstract threat — it was something that required young people from small towns like ours to risk and sometimes give their lives to stop.

Although it may not seem that long ago in the sweep of history, many of those who lived through World War II are no longer with us. Yet what they experienced — and what they remembered — has not been lost. Thanks to the care and dedication of Woodbridge neighbors like Edee Dahlin Lockyer (1934-2017), who began a project to preserve WWII-era local records and personal stories more than two decades ago, the legacy of that time remains close at hand. Through her work and that of others’ we are able to look back, name names, and reflect on the lives shaped by the war — both those who returned, and those who did not.

Among her many contributions to our community over decades, Edee undertook this remarkable project in 2001 to ensure that every World War II veteran from Woodbridge would be remembered as the community approached the re-dedication of the Woodbridge World War II memorial on November 11, 2001. In her own words in the preface to her research she described her project:

"In early September of 2001, I set out to compile a list of the names that appeared on The Honor Roll. I am personally aware of many of the people who had served, so I started with a list from memory. My next step was to walk through the three cemeteries located in town. The final step was to do research at The Town Clerk's Office. The resources I used were the record book of veterans names, discharges filed with the Town Clerk, and tax records from 1942, 1943 and 1945. In with the records of discharges filed, I found lists of people serving in 1942, 1943 and 1944 and a list of Veterans of World War Two. With the information I had already found I verified the list and have made a new copy."

LET US NOT FORGET

Edee Lockyer

October 30, 2001

Edee's work to commemorate WWII lives on in the binder of research she created, now housed at Town Hall. It remains one of the most comprehensive records of Woodbridge’s wartime service, including that of the 10 men who did not survive, and is a reminder that the history of great events is often preserved by those who care enough to remember. A collection of memorials on the Find-a-Grave website is another resource that commemorates the service of those from Woodbridge and Bethany during WWII. Here are some of the stories of those who did not return:

The final resting place of William Garry Smith near Omaha Beach in France.

Technician Fifth Grade William Garry Smith, born on July 2, 1916, and raised on Overlook Road in Woodbridge, served with the 53rd Armored Infantry Battalion of the 4th Armored Division, a unit known for its speed, strength, and pivotal role in the liberation of France. While he did not land on D-Day itself, William came ashore at Utah Beach on July 11, 1944, as part of the Allied effort to expand the beachhead and break through entrenched German defenses. Just weeks later, during the rapid push through Brittany, William was killed in action on August 4, 1944, in the Morbihan region of western France. He was 28 years old. Buried at the Normandy American Cemetery in Colleville-sur-Mer, his grave lies not far from the cliffs above Omaha Beach—an enduring symbol of the cost of freedom and the men who carried its banner forward.

Seaman Anthony S. Dzikas of Baldwin Road in Woodbridge was lost at sea on May 28, 1945, when the USS Drexler, a destroyer on radar picket duty, was sunk by kamikaze attacks off the coast of Okinawa. The attack came during the final major battle of the Pacific war and resulted in heavy loss of life. Dzikas was one of more than 150 sailors who perished in the attack. His name is engraved among those lost at sea on both a memorial in Okinawa, Japan as well as another memorial in Honolulu, Hawaii —a solemn reminder of the risks faced not only in battle, but in protecting the broader mission of the fleet during one of the war's most critical operations.

William T. Gilbert Jr. is memorialized with a cenotaph marker in the family plot at Eastside Cemetery in Woodbridge and also in the Netherlands.

First Lieutenant William Thurston Gilbert Jr. of Rimmon Road in Woodbridge served as a fighter pilot with the 362nd Fighter Squadron, piloting the iconic P-51 Mustang. On December 24, 1944—Christmas Eve—he was engaged in a fierce dogfight over Germany when his plane was hit and engulfed in flames. Despite his injuries, he downed an enemy plane before bailing out. Tragically, his parachute became entangled in a tree, and he did not survive the descent. He is buried at the Netherlands American Cemetery in Margraten, Holland. His courage in the skies exemplifies the bravery and sacrifice of young airmen who risked — and gave —their lives to defeat tyranny.

Bernard C. Johns of Amity Road in Woodbridge also served in the U.S. military during World War II and was killed in action. While the details of his death during the war are not readily available, he is remembered for his service, courage, and ultimate sacrifice along with the others who served from Woodbridge.

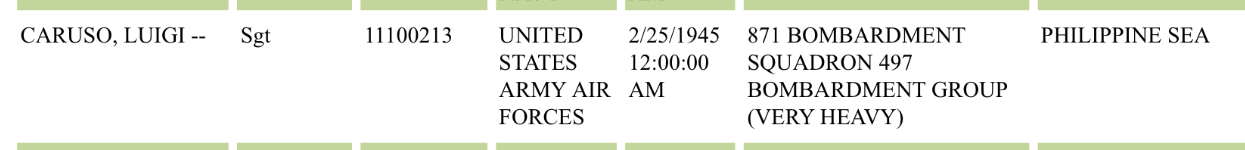

Louis Caruso of Merritt Avenue in Woodbridge also served during World War II. While detailed records of his service and the circumstances of his death are limited, he is listed among the town’s honored war dead. Like so many young men of his generation, Caruso answered the call to serve at a time of great global uncertainty. His name is included among those who made the ultimate sacrifice, and his service continues to be remembered with honor and gratitude.

Update: After seeing an article on April 18, 2025 published in the New Haven Register about an East Hartford native, I was able to search an online database and found Louis Caruso listed as Luigi Caruso. According to the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency, the following details about Caruso are available:

With this new information I was able to also locate a memorial on Find-A-Grave for this soldier and I have added it now to the collection of World War II soldiers from Woodbridge and Bethany. According to the memorial for Sgt. Luigi Caruso:

Luigi served as a Sergeant & Tail Gunner on B-29 "Ponderous Peg" (#42-63431), 871st Bomber Squadron, 497th Bomber Group, Very Heavy, U.S. Army Air Force during World War II.

He resided in New Haven County, Connecticut prior to the war. He enlisted in the Army on October 7, 1942 in Hartford, Connecticut. He was noted, at the time of his enlistment, as being employed as a Sales Clerk and also as Married.

Luigi was declared Missing In Action (MIA) when his B-29, while on a bombing mission to Tokyo, collided with B-29 (42-24803) and crashed during the war. He was awarded the Air Medal and the Purple Heart. His remains were not recovered.

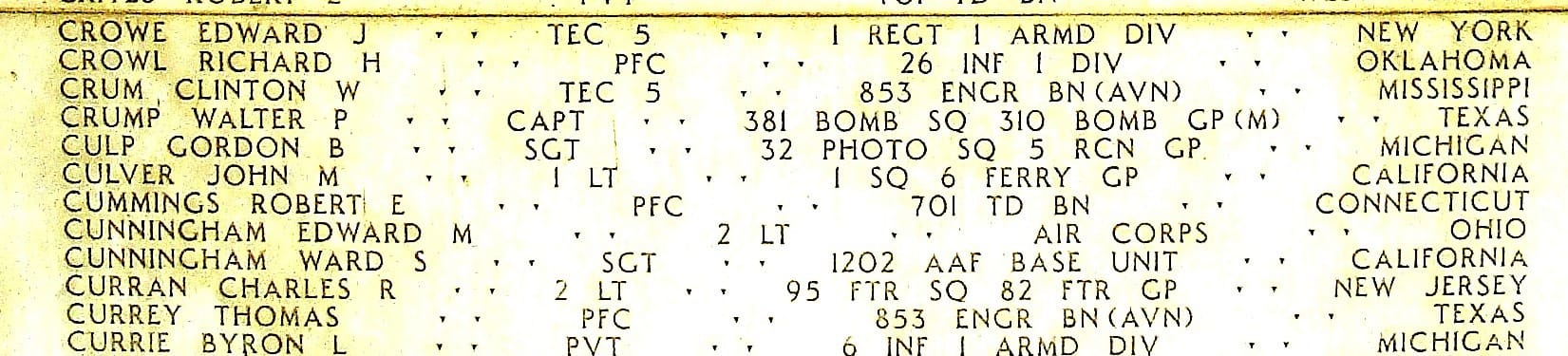

Private First Class Robert E. Cummings of Beecher Road in Woodbridge gave his life in one of the earliest and most critical campaigns of World War II: the fight for control of North Africa. Serving with the U.S. Army, he was killed in action on February 14, 1943, during the intense engagements of the Tunisian Campaign, as Allied forces battled to push Axis troops from the continent. Though the specific circumstances of his death are not known, the date suggests he fell during the buildup to the Battle of Kasserine Pass, one of the most fiercely contested early battles involving American ground forces. He was 28 years old. PFC Cummings is memorialized on the Tablets of the Missing at the North Africa American Cemetery in Carthage, Tunisia — a lasting tribute to those whose final resting places remain unknown, but whose sacrifice shaped the course of the war and the world to come.

The final resting place of Walter Charles Goodrich in France.

Sergeant Walter Charles Goodrich, born on December 24, 1922, in East Haven, Connecticut, was a resident of Walker Lane in Woodbridge during his youth. He served in the 179th Infantry Regiment of the 45th Infantry Division during World War II. On January 10, 1945, at the age of 22, Sgt. Goodrich was killed in action in France. He is interred at the Epinal American Cemetery and Memorial in Dinozé, France, which honors American soldiers who lost their lives during the liberation of France. The 45th Infantry Division, known as the 'Thunderbirds,' was actively engaged in the European Theater, participating in significant campaigns across Sicily, Italy, France, and Germany. While specific details of Sgt. Goodrich's service are limited, his sacrifice during this critical period underscores his dedication and bravery.

Frederick Walter Halloway, Jr. is commemorated at both Eastside Cemetery in Woodbridge, CT and at the military cemetery in Cambridge, England.

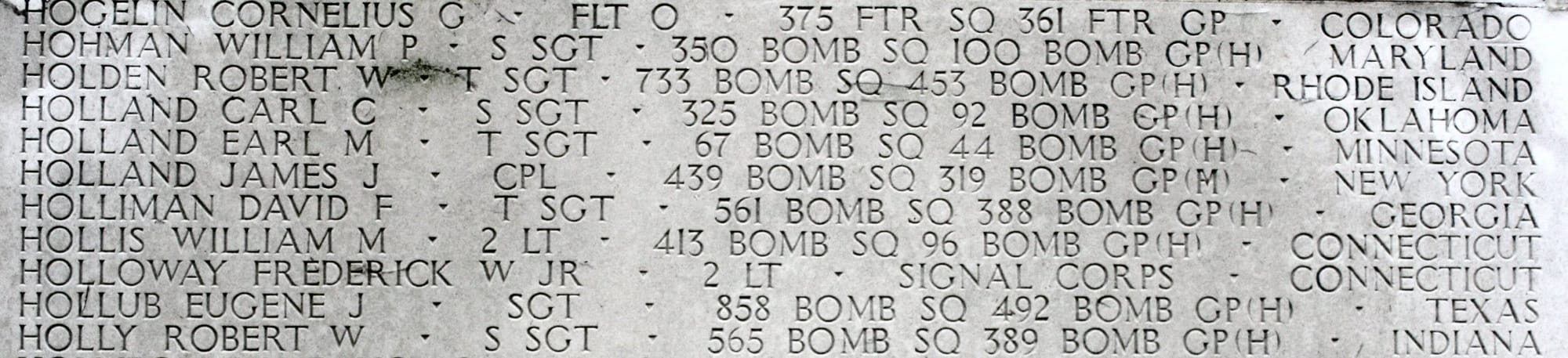

Seaman Second Class Frederick Walter Holloway Jr., a resident of Seymour Road in Woodbridge, was lost at sea on February 7, 1943. Although the exact circumstances of his loss remain unclear, the date and memorial location suggest he may have been involved in a naval operation during the height of the Battle of the Atlantic. He is memorialized at the Cambridge American Cemetery in England, where many who were lost at sea or had no known grave are honored. His name lives on among those whose final resting places are unknown, but whose contributions to the war effort were vital and courageous.

Henry Baldwin Sattig is commemorated at this military cemetery in the Philippines.

First Lieutenant Henry Baldwin Sattig, born May 7, 1917, and raised on North Race Brook Road in Woodbridge, served in the India-China Wing of the Air Transport Command in the U.S. Army Air Forces. He flew critical supply missions over the Himalayas — routes known as 'The Hump' — to support Chinese forces and Allied efforts against Japan. On January 19, 1946, months after the war had officially ended, Lt. Sattig was declared missing in action. He is commemorated on the Tablets of the Missing at the Manila American Cemetery in the Philippines. His service stands as a testament to the quiet heroism of those who risked their lives not in battle, but in the sustained effort to win the war from the air.

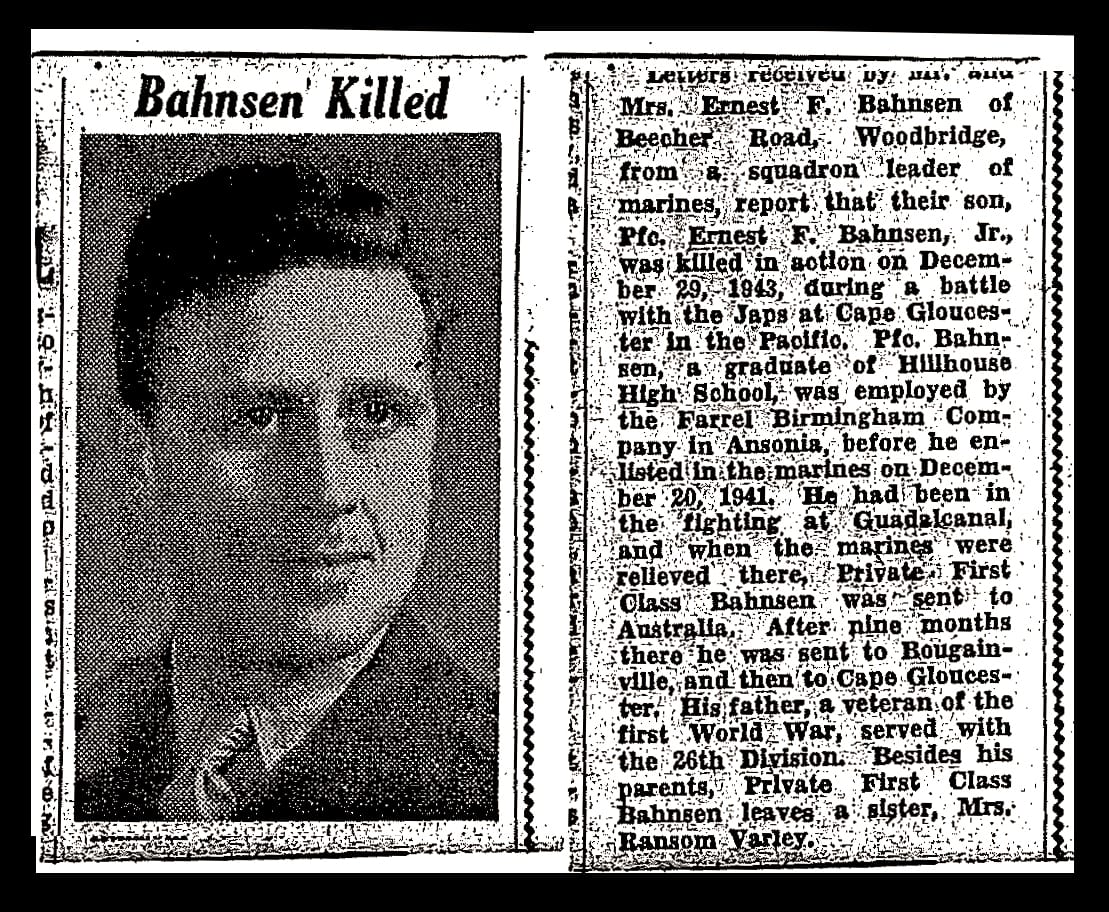

Private First Class Ernest Frederick Bahnsen Jr., of Beecher Road in Woodbridge, enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps on January 10, 1942. He served with the 1st Marine Regiment, 1st Marine Division, one of the most storied units in the Pacific Theater. On December 29, 1943, PFC Bahnsen was killed in action during the Battle of Cape Gloucester on New Britain Island in what is now Papua New Guinea. He was posthumously awarded the Purple Heart. His life and service remind us of the fierce and costly island battles waged in the Pacific, where Marines faced intense combat in jungle terrain far from home.

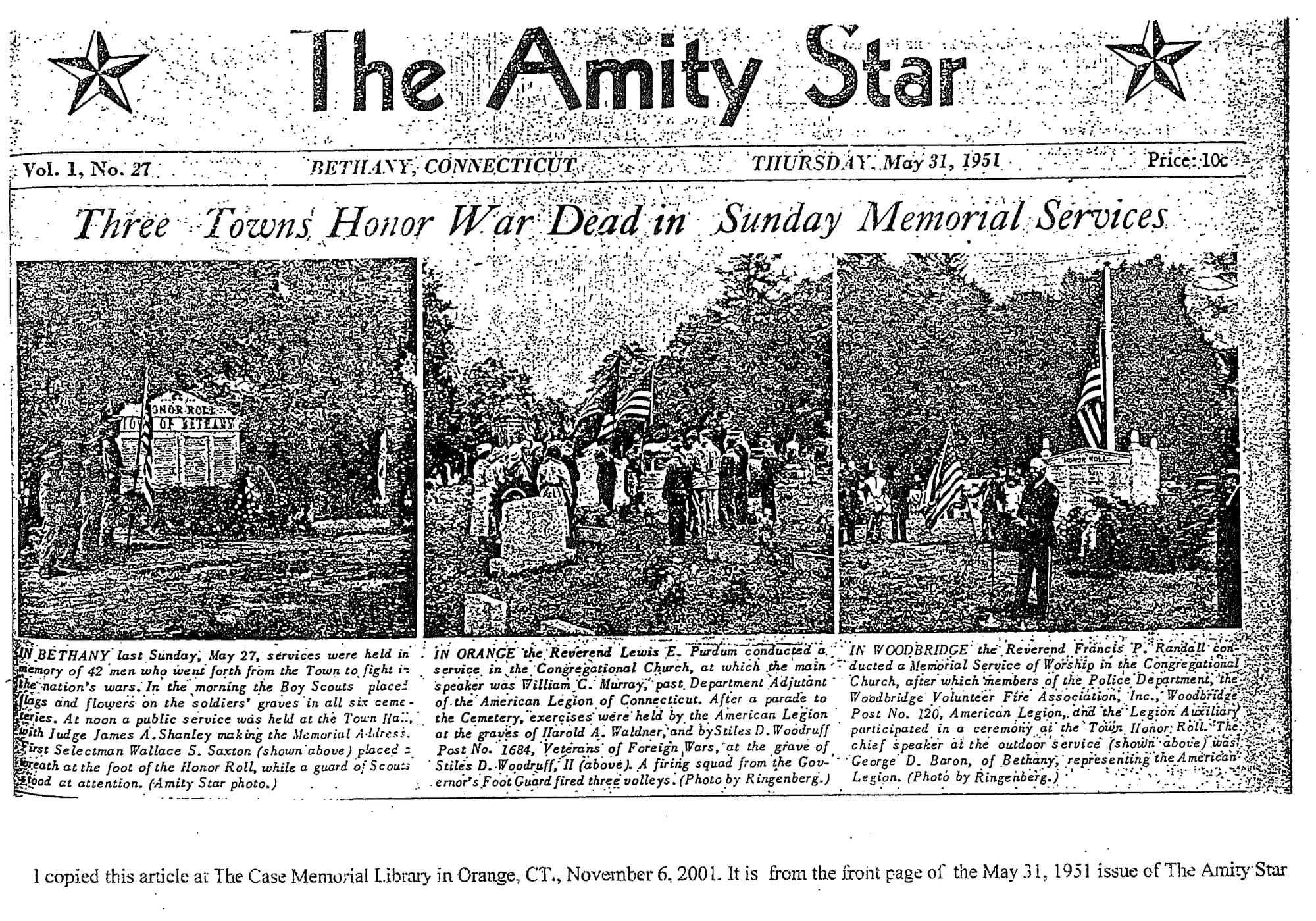

While many of these stories come from Woodbridge, our neighboring town of Bethany also sent its sons and daughters to serve during World War II. Their names are preserved on monuments that stand quietly in the center of town and in Veterans Memorial Park, honoring those who left rural New England for distant battlefields and never came home. Among these local stories is that of the Hoppe family, whose experience of wartime service and loss offers a poignant window into the cost of war — and the strength of those left behind.

Wall of Honor and WWII Memorial Marker in Bethany, CT.

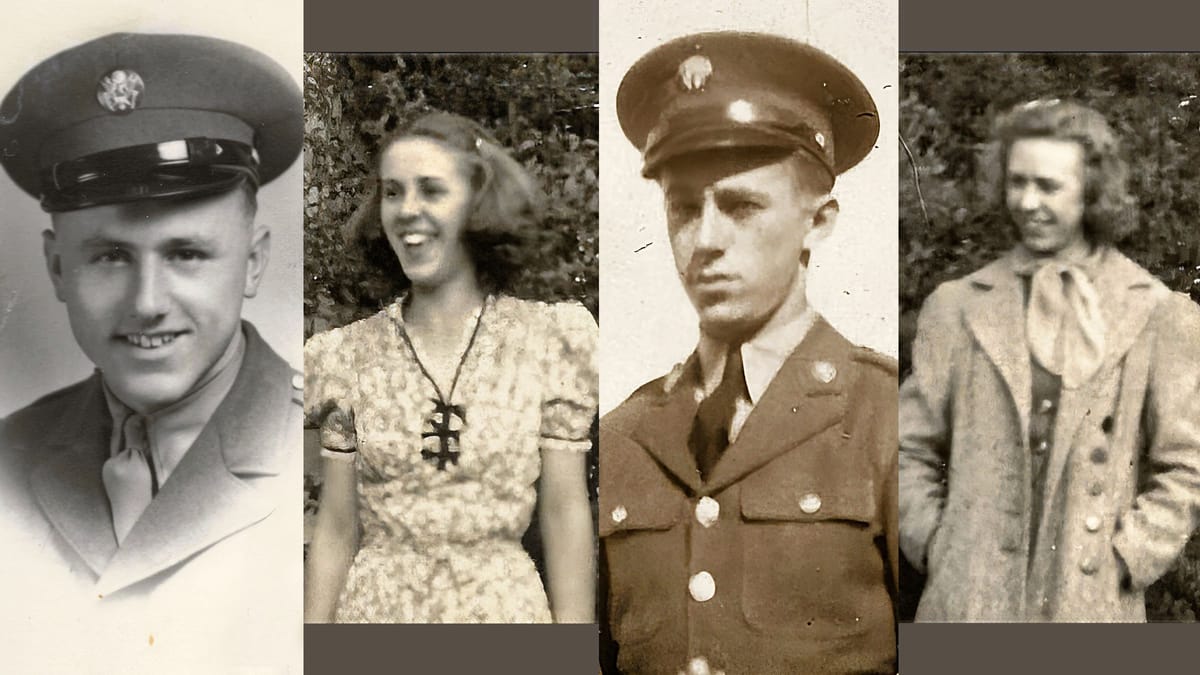

Edmund Hoppe (1892-1964) who emigrated to America from Poland, and his wife Anna Gerber Hoppe (1891-1971) raised their six children in Bethany. Three of this couple's four sons served, and one never returned. Corporal Franklyn R. Hoppe, born in 1922, enlisted in the Army Air Corps and became a gunner with the 8th Bomber Squadron, 3rd Bomber Group, Light, flying A-24 dive bombers in the Pacific Theater. On a mission to attack Japanese ships near New Guinea, Franklyn’s plane was hit by enemy flak and crash-landed in the jungle. He and his pilot were both injured but survived the crash. Friendly local villagers led them to Australian spotters nearby. A radio message on July 30, 1942, reported that the crew was safe—but the transmission abruptly ended and was never resumed. It is believed that Franklyn and the others were captured and executed by Japanese forces, possibly on August 8, 1942. He was just 20 years old. Franklyn was posthumously awarded the Purple Heart, and after the war his remains were returned to the U.S. and reburied in 1950.

Franklyn’s older brother, Edward Edmund Hoppe, also served. He returned home after his service but died not long after the war ended, in 1946 at age 31. A third brother, Harris Kenneth Hoppe, born in 1923, served in the U.S. Army Air Forces, rising to the rank of Master Sergeant. He survived the war and lived to an advanced age. During the war, the family’s losses extended beyond the battlefield. Their sister Mildred Eleanor Hoppe, just 23 years old, was engaged to a local soldier named Albert J. Spencer during the war. On December 10, 1943, while Albert was home on leave, he and Mildred were involved in a serious car accident on the Litchfield Turnpike. Mildred was ejected from the automobile and died instantly as result of head injuries, while Albert survived. He went on to marry Mildred's sister Lillian Hazel Hoppe after the war.

Another of the Hoppe siblings, William Frederic Hoppe, did not serve in the military due to his employment with Sealtest Dairy, which was considered part of the nation's essential civilian workforce, ensuring the steady production and distribution of food during wartime. His role supported the home front effort — an equally vital part of sustaining troops overseas and civilians at home. Before the war he married Hazel Lounsbury (my grandmother's sister). Hazel went on to author several books — and with her writing, also help preserve the stories of Bethany for future generations. Through Hazel’s books and William’s quiet ties to a family marked by extraordinary sacrifice, the Hoppe legacy lives on in the collective memory of the town.

Today, eighty years after these wartime sacrifices, the Army Talk pamphlet series is no longer how we engage with the great questions of democracy. Instead, viral videos, social media posts, and online platforms have become the tools for education and public reflection. But the study of fascism — and the responsibility of citizenship — remains as urgent as ever. Historian Timothy Snyder, in his book On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons from the Twentieth Century, continues the work once carried out in field tents and mess halls: helping citizens understand the threats to freedom and the habits that sustain democracy. Just last month, actor John Lithgow gave voice to Snyder’s lessons in a recorded reading, now available to watch and share online. It is a timely reflection, given this anniversary year, and a fitting way to honor those whose sacrifices secured the freedoms we will forever be called upon to uphold.