Friends of the 1897 Woodbridge and Seymour trolley line

“A Woodbridge man stated, the other day, that if a trolley line was in operation to Woodbridge there would be ten times the amount of building there has been and the number of houses would grow tenfold in a very short time.”

In the late 1890s, an effort was underway to build out the New Haven trolley line to extend along Whalley Avenue from Westville all the way up Amity Road to the corner of Seymour Road — and eventually from there into the town of Seymour itself. Known as 'the electric rail road' in the days before the invention of the automobile, street trolley lines were an important driver of development — and there was no shortage of ambition in The Hills of Woodbridge to connect the old town to this growing network of transportation. A news article in the New Haven Morning Journal and Courier on November 20, 1897 tells the tale:

New Haven Morning Journal and Courier

November 20, 1897

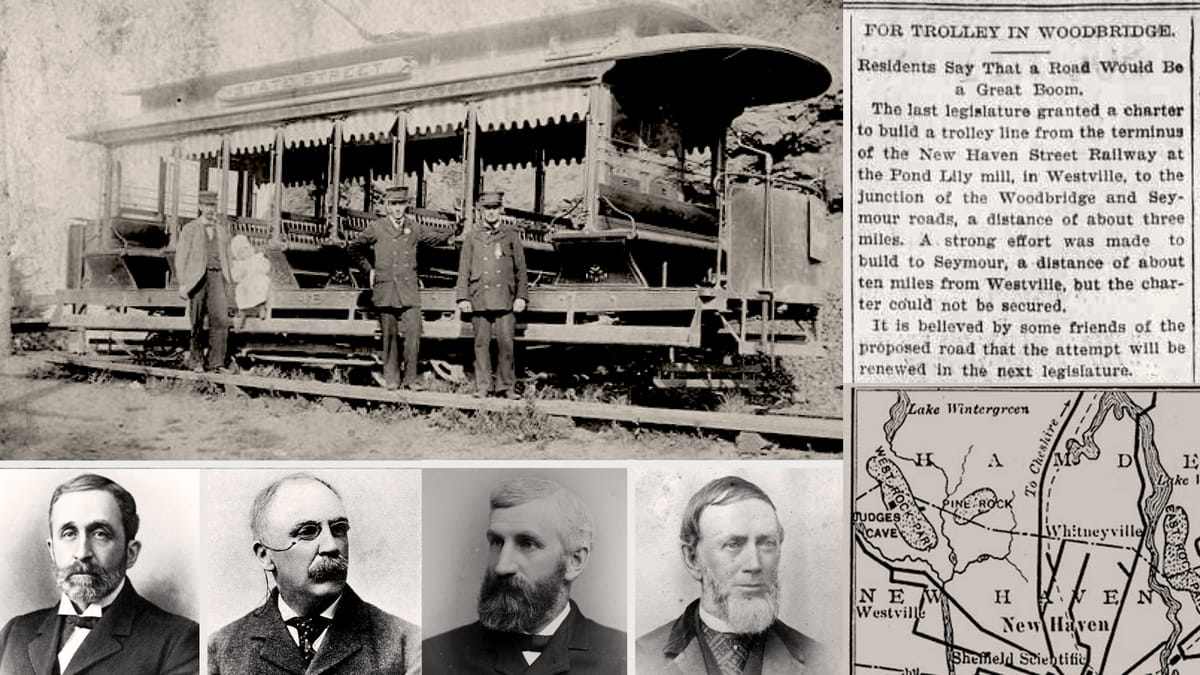

FOR TROLLEY IN WOODBRIDGE.

Residents Say That a Road Would Be a Great Boom.

The last legislature granted a charter to build a trolley line from the terminus of the New Haven Street Railway at the Pond Lily mill, in Westville, to the junction of the Woodbridge and Seymour roads, a distance of about three miles. A strong effort was made to build to Seymour, a distance of about ten miles from Westville, but the charter could not be secured.

It is believed by some friends of the proposed road that the attempt will be renewed in the next legislature. Considerable disappointment was expressed by people living along the proposed line when the petition for the charter failed before the last legislature, as their hearts were set upon the enterprise. They came to the conclusion that the project was not dead, however, but would be heard from again.

Since the petition was summarily disposed of, so far as Woodbridge and Seymour are concerned, there has been created a demand for the line to Woodbridge really greater than before, in view of the improvements in that town during the past summer, by a Mr. Andrews of Chicago, a well-to-do merchant, who has expended nearly $8,000 on the John Peck place, in Woodbridge, and has resided there through the summer and will remain until it is time to g0 south. Several other improvements have been made and the old town is really looking up.

A Woodbridge man stated, the other day, that if a trolley line was in operation to Woodbridge there would be ten times the amount of building there has been and the number of houses would grow tenfold in a very short time. Already a goodly number of New Haven families reside in Woodbridge during the summer, including the familles of M. F. Tyler, Judge A. Heaton Robertson, Dr. T. H. Russell and E. P. Arvine, and it is believed that the number would increase rapidly if a better system of communication was afforded.

Those interested in the Westville and Seymour line included T. H. Russell, E. P. Arvine. R. C. Newton and Dwight N. Clark. While the proposed company is not likely to build the three-mile section from the Pond Lily mill to the Seymour road at present, the securing of the charter is looked upon as a starter. The company is likely to go to the next legislature and make a big fight in favor of their pet scheme and, if they are successful, it is understood the line will be built very soon afterward.

The line from Westyille to Woodbridge would be about five miles in length, affording one of the finest suburban rides out of New Haven. Several years ago, a project was started to build a summer hotel on one of the highest Woodbridge hills. The scheme never materialized, but if the trolley road was built it would prove quite a little inducement to carry out the hotel project. Friends of the Woodbridge and Seymour trolley road have great faith in the next legislature. While opposition is to be expected, there is prospect that a big effort will be made to secure a charter for the new railroad.”

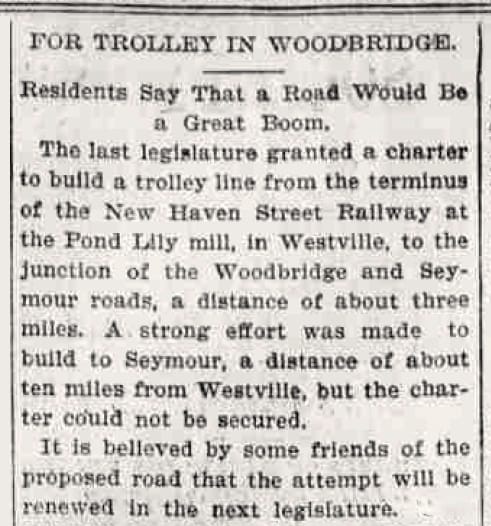

Let's round up this collection of 'Friends' – here we have, clockwise from top left: Thomas Hubbard Russell (1851-1916), Earliss Porter Arvine (1846-1914), Dwight Noyes Clark (1829-1922) and Rollin Clark Newton (1846-1933).

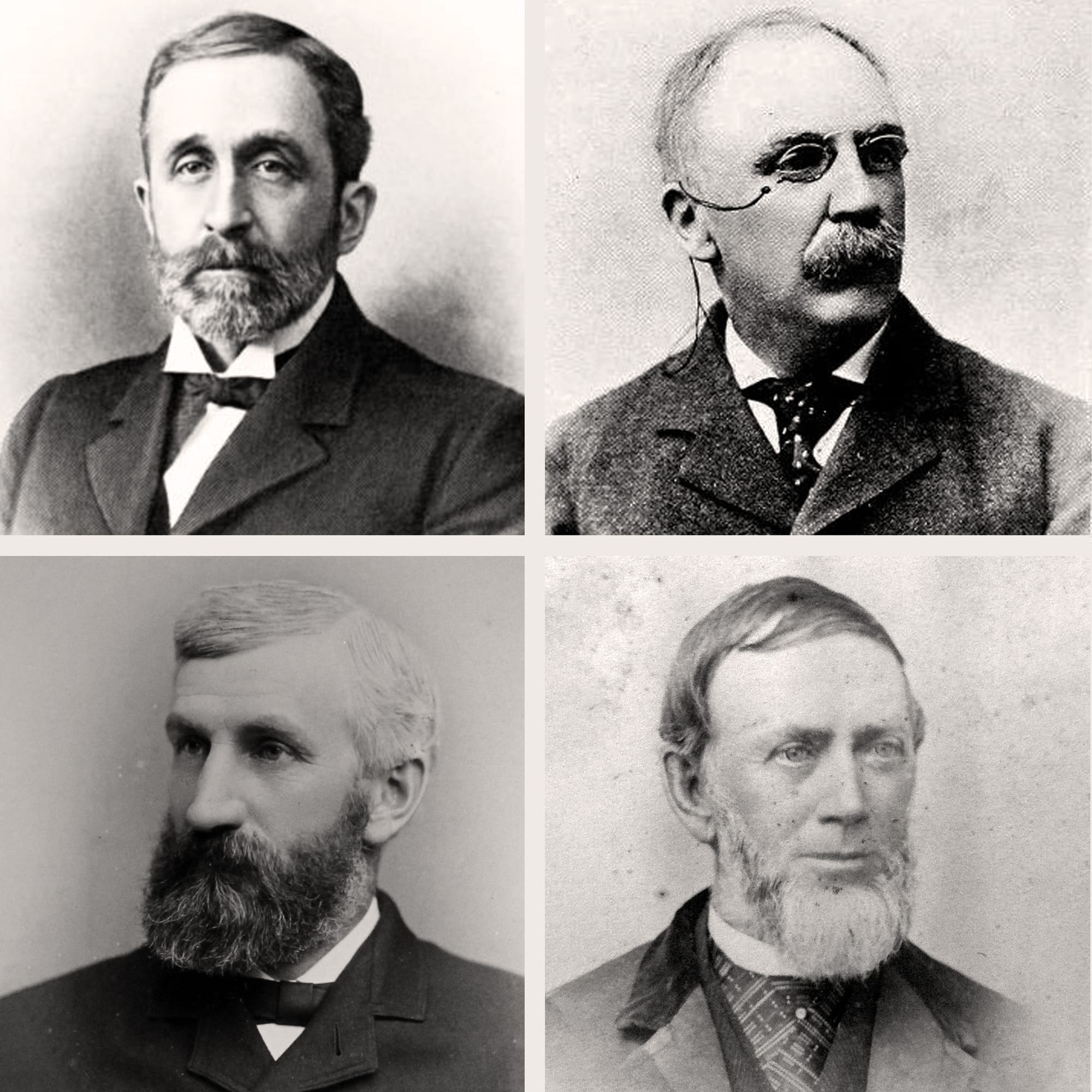

Let's also picture the trolleys of this time period, to a get a sense of the future held in the imaginations of this group of friends endeavoring to transform Woodbridge at the dawn of the century. From the website of the Shoreline Trolley Museum there's a wealth of detail about the New Haven-area trolley system, including a few old photos of trolleys from this era.

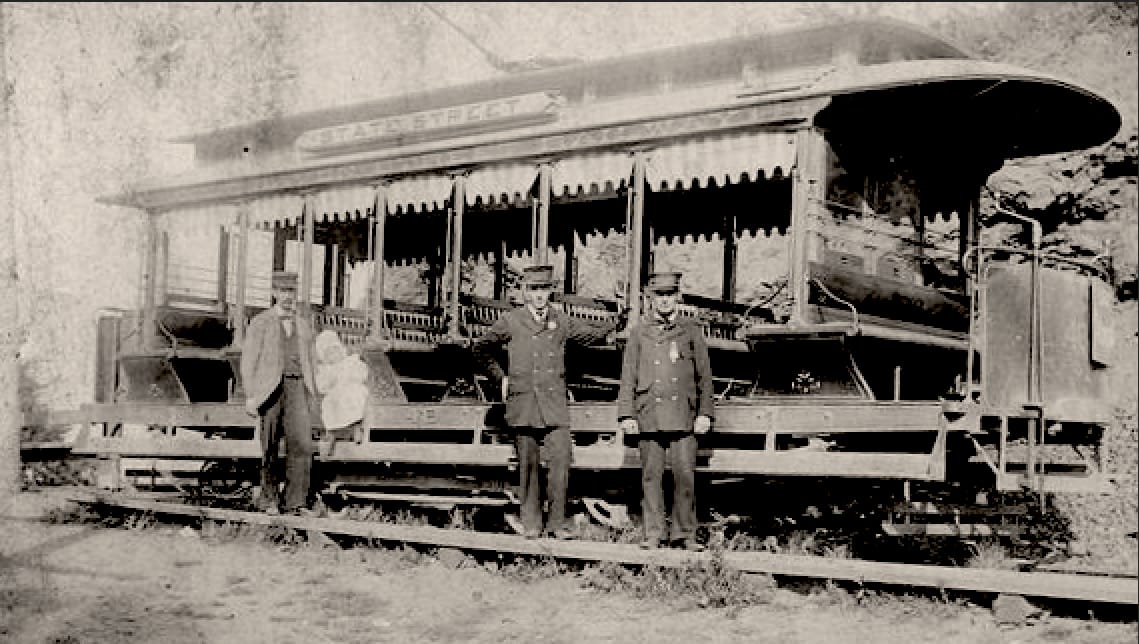

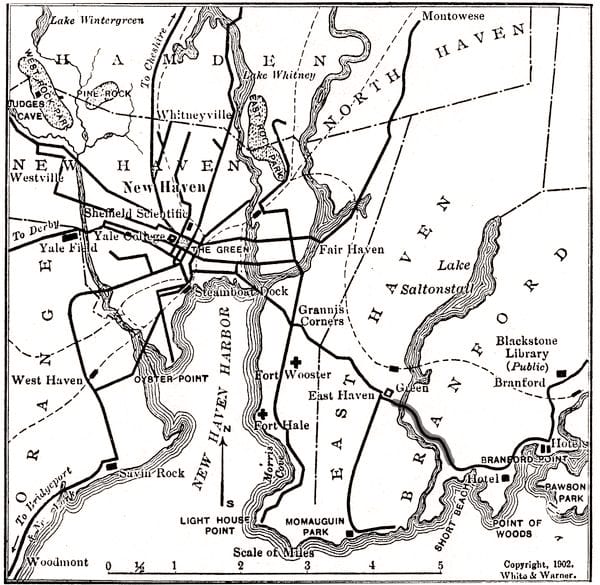

And here is a map from 1902 showing the various trolley lines in and around New Haven at about this time.

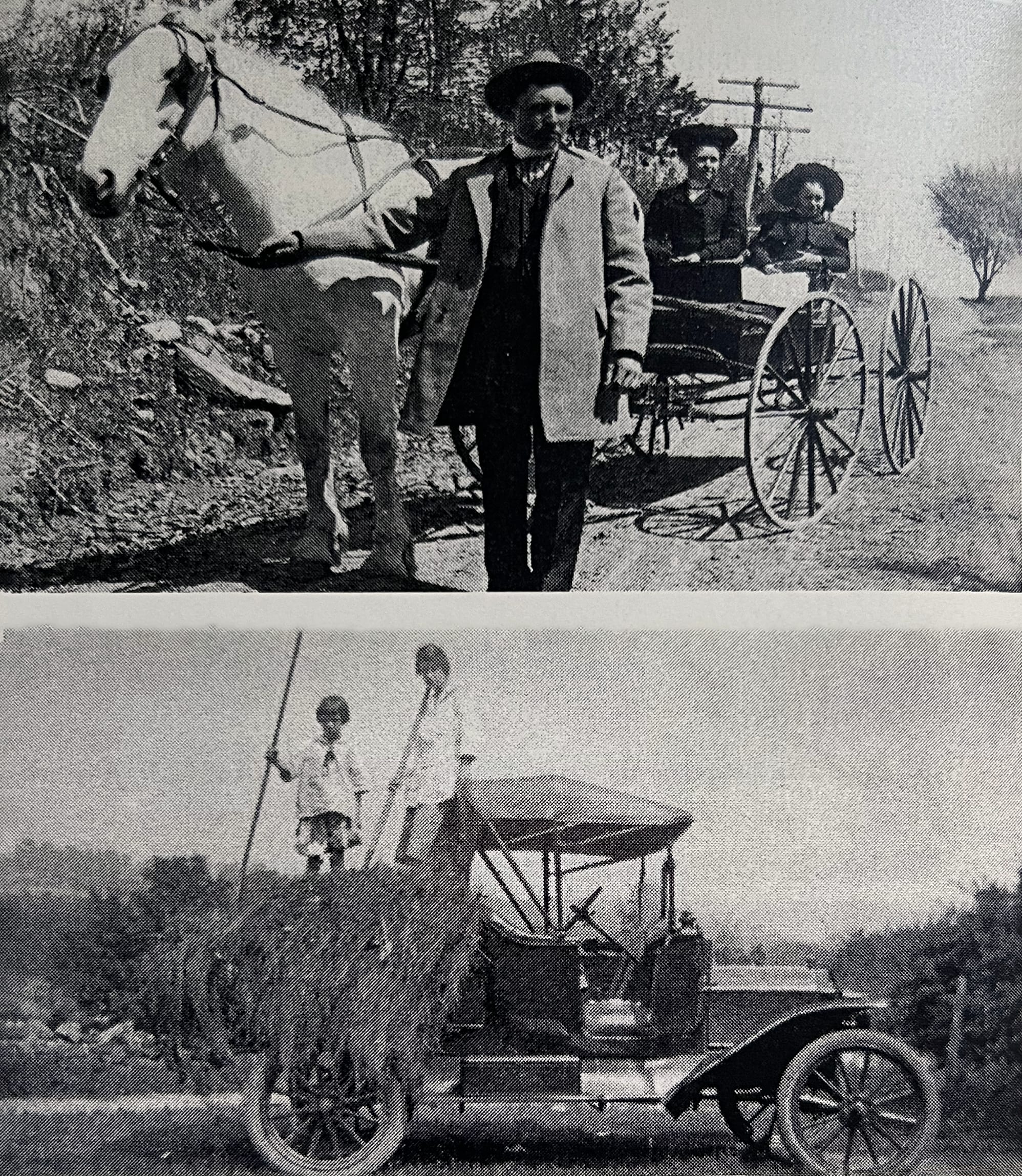

Let's step back a moment to capture what life was like in Woodbridge at this time. Hazel Lounsbury Hoppe (1918-2008) — the author's grand-aunt — describes her upbringing on a farm up the road from Woodbridge in the early decades of the 20th century in her book Bethany Pebbles & Flowers: Memories of Life in a Rural Connecticut Town, published in 1997.

“During those years around the turn of the century when horse and carriage were the preferred methods of travel, a stagecoach still ran twice weekly between Waterbury and New Haven. Meanwhile, out in Detroit, Henry Ford had been experimenting with a gasoline engine that would revolutionize the mode of travel for everyone. The day was soon to come when walking, the bicycle, and the faithful horse were all outdated.

In the month of April, in the year 1900, Tyler Davidson recorded in his journal, “First time that an automobile passed through the town, at least as far as we have knowledge.” No mention was made of where this earthshaking event occurred, but one of the main roads must have been the setting. The more general use of the automobile soon brought about the demise of the stagecoach as well. The last trip of that ancient vehicle through Bethany took place in the spring of 1907.

Thus began the slow transition from the old horse-and-buggy days to the days of the "flivver." Traditionally, the old-timers were reluctant to change habits that had served them well.”

Hazel also described her own family's experience in a conversation with her older sister Minnie Lounsbury Downs (1911-2003) recounted in her book, as they were discussing the days of the early automobiles: "Everyone else in Bethany was buying a car when we finally got our first horse," which the family named Prince.

“[We] were delighted to have Prince become a member of the family, especially since it was apparent that an automobile was not a choice for us in those days. My sisters recalled the pleasure that prevailed in our house on the morning that father brought home the horse and wagon.

"I remember how excited we were! It was Thanksgiving Day and we were having a terrible ice storm, but Pa went down and brought home Prince and the wagon anyway," Minnie told us.

From that day Prince became a loyal, hard-working member of our family. He pulled the wheels that transported us into the world outside our homestead area. He carried us down the turnpike to the trolley cars, which in turn took us down Whalley Avenue to the New Haven Green and the exciting stores filled with treasures, our ultimate happy destination. He carried us to Bethany Center on Sunday mornings, where we worshipped at the Episcopal Church while he rested in the sheds across Amity Road. He gave Mama the freedom to visit her many friends around town in those days when visiting was a large part of our social life. He pulled the surrey with the fringe on top in those years when my parents transported students to the one-room Beecher School during the mid-twenties. Last but not least, Prince pulled the plow that prepared the soil for the vegetable garden, and he pulled the farm wagon filled with hay to be stored in the barn.”

As described in the introductory essay of the 'Historic Woodbridge' book, when the effort to build out the trolley line up into the Woodbridge hills was thwarted by the geology of the landscape, time marched on and the automobile came to dominate as the chief economic driver of development in and around our community.

“By the turn of the century Woodbridge's isolation from the mainstream was becoming a decided asset. People were already starting to leave the cities for the haven of quiet rural towns and the concept of suburbia was born. The first streetcar suburbs began to blossom near Hartford and New Haven, Connecticut's largest cities. Both cities were congested and heavily industrialized; early signs of suburban development in their surrounding towns were already evident even before World War I. Because it was accessible by trolley, Hamden took an early lead in the New Haven area; its population had reached 23,373 by 1940, a five-fold increase over 1900. Although townspeople agitated for years for trolley service, Woodbridge's rugged terrain precluded the laying of tracks; the electric streetcars that had replaced the old horse cars came only as far as its southern border. Any substantial growth here depended on a newer form of transportation, the automobile, which brought seasonal dwellers, permanent residents, and even tourists to town. When autos came into common use after World War I, the population of Woodbridge doubled in the next two decades, reaching 2,262 in 1940. After the Merritt and Wilbur Cross parkways were completed, the latter along the town's southern border, Woodbridge joined the other burgeoning bedroom communities along these routes. As many other places discovered in the massive suburbanization that took place after World War II, however, suburban growth was a mixed blessing which strained town resources.”