Mrs. Rice and her pond: a glimpse of the past through the trees

Traveling along Center Road just past the Woodbridge town center heading west, after passing the ballfields and children’s playground, you may glimpse what remains of the former home of Mrs. Rice. Her property is now owned by the Town and the house itself has been subsumed into the surrounding woods with only the remnants of a stone chimney, foundation, and patio remaining visible through the trees from the street. But while Mrs. Rice’s home has all but disappeared from sight, the legacy she left behind has not faded from memory — there are still some folks in Woodbridge who recall the days when the site once buzzed with life, especially in winter when it echoed with the sounds of children ice skating on the pond behind the house.

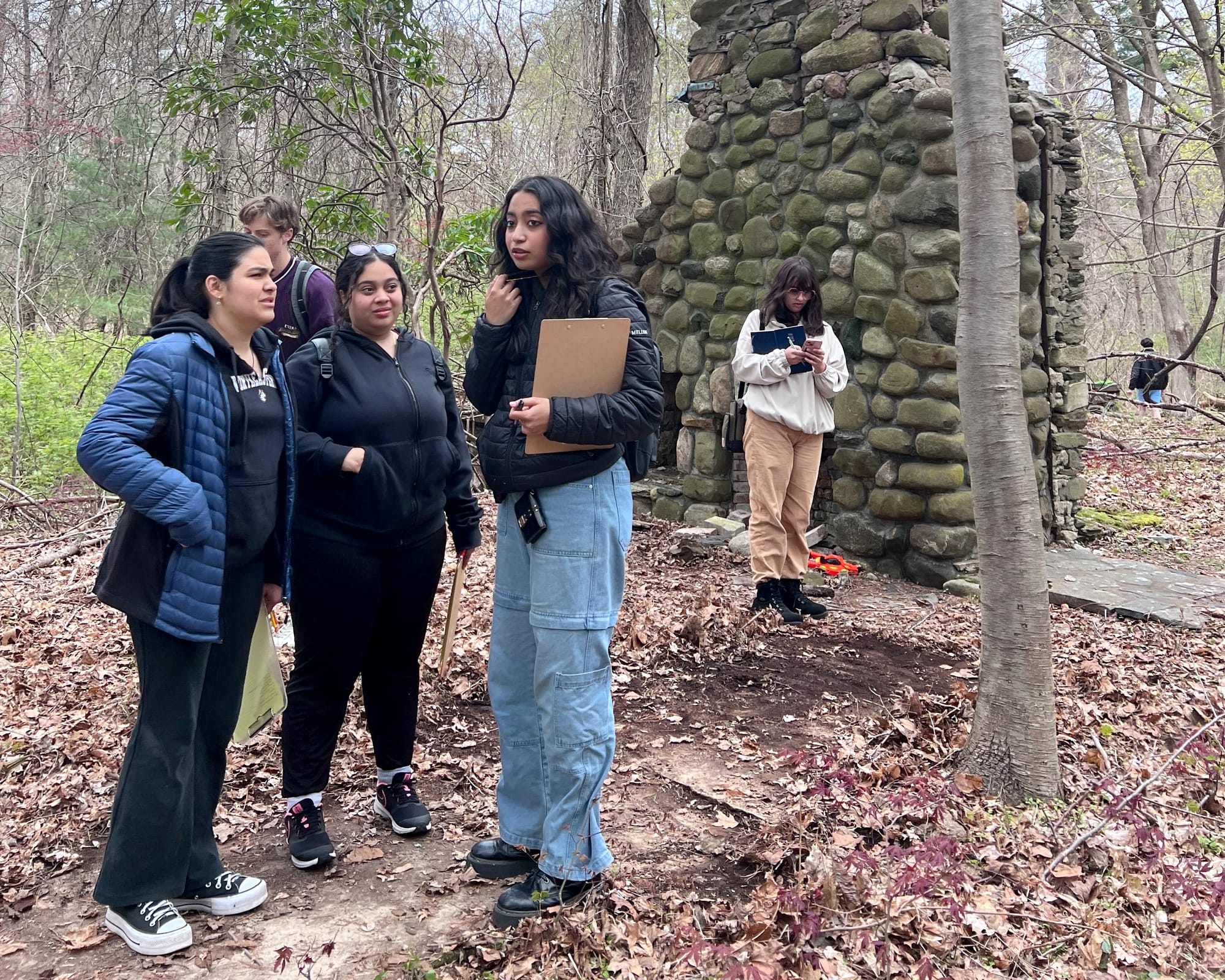

Mrs. Rice’s home was a modest dwelling but must have held a distinct charm. The house itself was crafted from a converted barn which was relocated from another site nearby. The fireplace and chimney stack rising through the trees, constructed with river rocks, and the remnants of the home’s former patio that once overlooked the pond on the property are just some of the clues that remain for students from Yale taking an introduction to archaeology class when they visited the site last spring. They were there to complete an assignment to interpret and date the remains of the house based on careful field notes of what they found on their visit.

Professor William Honeychurch, who leads these archaeological visits with his class, explained the students' process, saying “When we visit the Rice property, while we cannot excavate, we are mapping and analyzing the surface structures. I ask my students to date the site based on the materials they find—bricks, river rock, the remains of the fireplace. We treat it like detective work, piecing together the story of the house.”

Yale students and professor William Honeychurch visited the Rice property in April 2024 and discussed the site with the author and neighbor Jen Just, who displayed some of the items she has found in the vicinity.

During the most recent student visit, Jen Just who lives next door to the Rice property, brought out some objects she has found nearby over the years. Excavating and studying a midden — a term used to describe a refuse heap where people disposed of waste materials such as household tools, pottery shards, or other everyday items — helps piece together a fuller picture of the activities and culture of those who lived in the area. These items offered the students some valuable insights into the daily lives of past inhabitants.

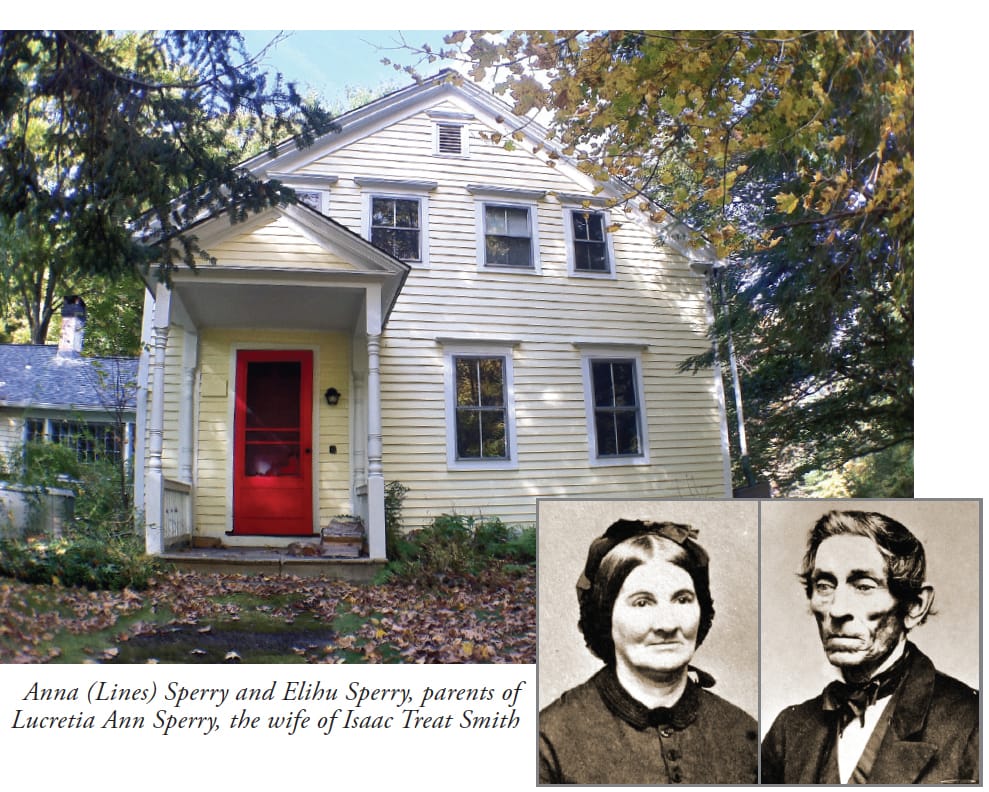

The history of the house next door at 157 Center Road, known as the Isaac Treat Smith house, is described in the Historic Woodbridge book and offers some background of the area before Mrs. Rice’s house came to occupy the land here:

“The first indication of a dwelling here appears on the 1868 map and it is identified as belonging to Isaac Treat Smith, probably part of the estate of his brother Lewis Smith (1807-1862) conveyed to him in 1863. That transaction also included the blacksmith shop across the road, identified as being near the “house of Isaac Smith.” Isaac and Lewis were sons of Daniel Treat Smith and his wife Rebecca Sperry. Their sister Eliza was the first wife of Bevil P. Smith (see #125). Isaac married Lucretia Ann Sperry, a daughter of Elihu Sperry (1800-1881) and his wife Anna Lines (1805-1880). By the time Isaac sold the property in 1888 and moved to New Haven, his holdings included a sawmill and it is possible that he was the one who first dammed the Wepawaug here for this purpose. Between 1888 and 1892 the house and sawmill were owned by J. Henry Taylor. He sold them in 1892 to George Dinfelder, who only stayed here two years. Among the early twentieth-century owners was the Fresenius (aka Fresnius) Ice Company of New Haven, which harvested pond ice here. The company sold off the house lot to Elmer Chase in 1930, but retained the rest of the property.”

The pond behind Mrs. Rice’s property which was once a winter skating area for local children is no longer there today because the dam that created it has been removed. But aerial photos from the 1930s reveal what the pond looked like in its heyday.

Further information about the Rice property can be found in the 1982 survey report issued by the Town of Woodbridge’s Commission for the Use of Publicly Owned Property (CUPOP), which recounts how the parcel came to be owned by the Town. It states: “The nine acre parcel of land at 149-153 Center Road, which included Rice's Pond, a house and other improvements was acquired by the Town in a Warranty Deed from Lillian P. Rice on April 27, 1967 for a purchase price of $55,000. In purchasing the property, the Town granted lifetime-use to Mrs. Rice on a portion of the property and provided that she would be relieved of paying taxes, possible sewer assessment, or insurance on the property, but would be responsible for keeping it ‘in a reasonable state of good repair.’ ... This arrangement terminated with the death of Mrs. Lillian P. Rice in June, 1979.”

The CUPOP survey goes on to describe the home that originally stood on this property:

“This house is a charming, wood-shingled, wooden frame house of a story and a half. Built in 1928 from the remains of an old ice house and barns on the site it has a balconied cathedral ceilinged living room, three to four bedrooms, kitchen, two baths, two fireplaces, two basements, an attic, an attached garage, flag stone front patio and back raised terrace, screened now by ever greens from the road, its view to the back looks over its terrace and lawns to the Pond behind. The house needs considerable and costly repairs to put it in first class shape.”

With the above background in mind, CUPOP went on to make a series of recommendations to the Board of Selectmen with regard to the property that shed light on the decision making process over the years:

1. In 1977 the Commission recommended that a survey be made of the Rice Property, for which the Town has no map, and consideration be given to prospective Town uses of the house, when, in the future, it will revert to the Town after Mrs. Rice's death.

2. In September of 1979, after Mrs. Rice's death earlier in the year, the Commission recommended that Town agencies and Commissions, particularly the Recreation Commission (with its neighboring Center Field) and Commission on the Aging, be asked if they had need or use for the house.

3. In June 10, 1980, considering that there were no immediate or long range developed plans for Town use of the house; that its necessary repairs and maintenance, and particularly its adaptation to public use, would be very, very costly; and that it is a charm ing house for private use (but questioning the wisdom of the Town keeping property for private rental), the Commission recommended that it be sold "as is" with a minimum conforming lot size, not to include any part of the Pond and offering as little disturbance as possible to the Hitchcock Memorial Park area. The Commission was anxious to keep all the Town's frontage on the Pond and as much of the general area as feasible.

4. In January of 1981, when asked to reconsider its recommend ation, the Commission felt there were no new factors to be weighed and reiterated its June of 1980 recommendation.

5. In September of 1981, when told the house needed immediate work to be safe for continued habitation, and recalling its real reluctance to give up any of the land bordering the Pond or disturb the Hitchcock Memorial Play area, the Commission recommended the Town keep all of the Rice Property and allow the house to be razed. Eventually, it was felt, the Pond might be dredged and the whole piece be well used by the Town.

6. Again on March 25th, 1985, when the Commission met to reconsider their earlier opinion, four members of the Commission voted (with one abstention and one member absent) to recommend that the structure be demolished, if possible saving the fireplace, well and septic field. We also discussed the possibility of making a terrace where the house now stands. The House was demolished per Board of Selectmen recommendation, Spring 1985.

But just who was this Mrs. Rice? Born Lillian Pauline Day in 1892 in Wells, Maine, she married John T. Cook with whom she had a son, Russell Crossland Cook, born in 1910. Lillian and John divorced and she then married a World War I veteran, Herbert Newton Rice, in 1921 and the couple settled in Woodbridge in 1928. Lillian, though not a formal educator, was said to have ‘taught school’ at her home — likely operating a nursery school (a precursor to the home-based daycare centers of today), while Herbert sold automobiles in the New Haven area.

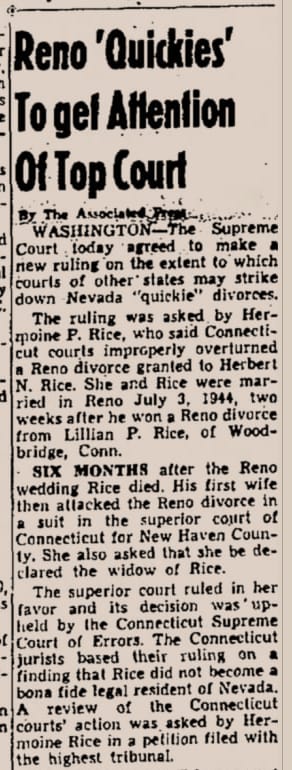

While Mrs. Rice's appearance in the above quoted town records tends to paint the picture of a quiet figure, living alone on the property after it has been conveyed to the Town, there's more to Lillian's story then first meets the eye. A newspaper clipping from 1948 informs us that Mrs. Rice was in fact the subject of a landmark U.S. Supreme Court case, Rice v. Rice, which revolved around the legality of the so-called 'quickie divorce' her husband Herbert obtained in Reno, Nevada shortly before his re-marriage and sudden death. The Court ruled in Lillian's favor finding that a Nevada divorce was not binding on other states if the person seeking the divorce did not have a bona fide residence in Nevada. As a result, Lillian was allowed to keep the house in Woodbridge on Center Road.

Lillian’s testimony during the trial paints a vivid picture of her life in Woodbridge and also adds details about the history of her property to the historical record. In one portion of the transcript she describes how an old barn, originally owned by Elmer Chase (mentioned above in the description of the neighboring Isaac Treat Smith house) on another plot of land, was acquired by her and her husband. She stated that they worked for Mr. Chase in exchange for the barn, which they later moved to the property so it could become their dwelling. Here is the exchange in her court testimony:

Q: How was that barn moved over to its present location on this property you are now occupying?

A: Mr. Rice and I hired some jacks and some rollers, and we jacked the four corners of the barn up and put the rollers under it, and with a truck that Mr. Rice had in his business, we pulled it across to its present location after Mr. Rice and I dug the cellar.

Q: Did I understand you to say that you and Mr. Rice dug the cellar?

A: Yes, indeed.

Q: You did some of the digging?

A: Yes, indeed.

Q: You did some of the work in moving the place, moving it over?

A: I drove the truck.

Q: After it was placed on the foundation in the cellar you had to dig, was the place remodeled?

A: Yes, it was remodeled.

Q: By whom?

A: By Mr. and Mrs. Rice.

Q: You did some of the work?

A: I did all the designing and all the planning and did most of the inside work with Mr. Rice.

Q: The inside work? You mean the decorating?

A: The decorating.

Q: And carpentry?

A: Yes.

During cross-examination, Lillian described her house in further detail as she explains that when her husband's automotive garage business was suspended, some equipment, tools, and materials were stored at their house, occupying space in the garage, cellar, and most rooms. This included typewriters, steel cabinets, parts, tools, a hoist, tires, and oil drums. She maintained that all this stored material not only indicated his intention to return to their home to reestablish his business, it also made it impossible for her to take in borders to help her financial situation since his death.

Q: You are still living in the place, the only place that Herbert N. Rice had in Connecticut when he died, that is true, isn’t it?

A: Yes.

Q: And you told us that he left an automobile there, didn’t you?

A: Yes.

Q: And you told us he left a lot of things that were in your garage, filing cabinets and various other things. You said they were all over the house.

A: They still are.

Q: Weren’t they all piled in the garage, right over the garage?

A: No, sir.

Q: What did they consist of?

A: They consisted of a typewriter and adding machine that is in my bedroom. There is a desk in one of my school rooms, and there is another desk that is on the balcony of my home, and there is a steel cabinet in another school room. There’s plenty of things you saw in my cellar. You saw all these things in my house, Mr. Morgan. You saw all the things that were in the garage. I would not attempt to name them because I don’t know the names of them, but it was oil cans and machinery of different kinds, a time clock, an oil burner, and tools of all sorts that would be used in the automobile business.

In a passage from the original divorce proceeding quoted in the subsequent case that ultimately went before the Supreme Court, we hear from Herbert himself. In this passage he is describing his marriage to Lillian as he attempts to dissolve it in Reno — and here, an incident involving the pond on the property in Woodbridge is recounted from his point of view:

Q: You had alleged in your complaint that since your marriage the defendant treated you with extreme cruelty which has seriously injured your health and destroyed your happiness and rendered further cohabitation unendurable and compelled you to separate. Is that true?

A: Yes.

Q: When did that cruelty start?

A: It started in 1924.

Q: And this continued to the time of your separation which took place when?

A: The day after Labor Day 1942.

Q: And you have lived separate and apart since that time?

A: Yes.

Q: Will you briefly explain to the Court what that cruelty consisted of?

A: She originally started out by accusing me of going out with every woman I came into contact with. I was an automobile salesman at the time, and my work took me from a man's office to his home, and I was constantly accused of running around with every one of my customers.

Q: On any occasion did she ever throw anything at you?

A: I would see every piece of silverware and every dish removed from the table and hurled at my head.

Q: On certain occasions, would she get up at night?

A: Yes. One occasion, she got up early in the morning and jumped in the pond, and it's not over five feet deep. There was no possibility of drowning in it, but I pulled her out and wrapped her in blankets; and after all those things, I would get up and go to work in the morning, thankful that it was morning so I could go to work.

Q: What effect, if any, did her treatment have upon your health and happiness?

A: It ruined my happiness and I commenced to lose sleep and I could not work and my work commenced to suffer. It made me very nervous and upset.

Q: And you actually gave up your business and moved away from that community on account of your wife's treatment of you?

A: Yes.

Q: There is no possibility of being reconciled with the defendant?

A: No.

Q: What is her business?

A: She runs a day school for pre- school age children.

Q: And she is financially independent?

A: Yes, and the last time I had a communication from her, she told me the school was a gold mine.

Q: There is no possibility of a reconciliation with the defendant?

A: None.

But this version of their marriage is not shared by Lillian, as she makes clear in her testimony. The Rice v. Rice decision in 1949 came at a time when divorce laws in the United States were undergoing significant scrutiny, particularly as women's rights began to evolve in the mid-20th century. In this way, the legal proceedings that surrounding Lillian offer us a window through which to view the changing role of women in our society at this time. While divorce proceedings then reflected the social norms of the time, Lillian’s independence and strength certainly shone through during the intense cross-examination she endured.

Q: You stated that you were running a school out at Woodbridge?

A: That's right.

Q: Are you a school teacher?

A: No sir.

Q: As I understand it you are running this school at Woodbridge?

A: Yes sir.

Q: You claim as I understand you that you are the widow of Herbert N. Rice?

A: Yes.

Q: When did you first learn that Herbert N. Rice was dead?

A: The first time Miss Malvina Pruneri called up the schoolhouse and asked Mr. Scholl to notify me of his death because she knew it would be such a shock and blow to me.

Q: Mrs. Rice when you were on the stand yesterday and telling your story about your married life were you trying to impress the court with the fact? Were you trying to give the court the impression that you and Mr. Rice had always gotten along beautifully from the time you were married right down to the time he left for Reno without your knowing anything about it?

A: I had no knowledge of his leaving for Reno and I did not try to impress the court with anything but the truth and the relations with my husband in my home. I said it was one of the happiest homes in Woodbridge and I think any one of my neighbors or friends can testify to that.

Lillian Rice’s stance in defiantly challenging the legality of the Reno divorce helps illustrate the era’s shift toward recognizing women’s rights within the institution of marriage. The case underscores how the legal system, while slow to change, was beginning to acknowledge the need for fairness in divorce laws and greater protection for women's autonomy within a strict legal framework. Although divorce was still stigmatized, cases like this laid the groundwork for future reforms in family law that would give women greater legal protections and more control over their personal lives. In pushing back against the legal boundaries and societal pressure placed on women in her time, Lillian Rice's plight reached the highest court in the land — and cemented her place in history as a trailblazer in America's evolving legal landscape.

~~~

Postscript to the community: Do you have memories of Mrs. Rice and the pond that once graced her property you would like to share? Did you know her? Do you know stories passed down through family, or recollections of skating on the pond? Please reach out by email. Your insights and knowledge can help paint a fuller picture of Woodbridge’s past, reminding us that local history is not just shaped by the headlines but also by the lived experiences of those who came before us. Through our community's collective memory, we can honor the complex history of figures like Lillian Rice and ensure their stories remain part of our town’s evolving narrative.