Oriented in a moving world: Reflecting on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and a Sperry family legacy

What does it mean to be free? And how do we ensure that freedom endures?

These are questions the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) was created to help answer.

“By 1945, six years of war had left many scars. There was widespread conviction that the war and its horrors had been caused, in large measure, by disregard and contempt for human rights. Society began to think and worry about man, about you and me, our human dignity, our rights. On the 10th of December, 1948, the United Nations General Assembly proclaimed the Universal Declaration of Human Rights as a standard of achievement to be pursued by all peoples and nations.”

The UDHR named rights—clearly, boldly, and without national limitation. Among them:

“The right to life, liberty, and the security of person. The right to freedom from arbitrary arrest. The right to fair trial. To freedom of movement and residence. To social security. To work. To education. To a nationality. To freedom of worship. To freedom of expression. The right of peaceful assembly. The right to hold public office. To seek and be granted asylum. To own property. To freedom from cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment.”

These and many more are the rights proclaimed in the Declaration, along with Articles 1 and 2, which set the tone for this landmark document:

Article 1: “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.”

Article 2: “Everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration, without distinction of any kind.”

To commemorate Human Rights Day in 1973, the 25th since the proclamation of the Declaration, United Nations radio presented a show titled, Born Equal and Free. It was described as a review of “the concepts and ideals which inspired this document, and of the successes and failures of the continuing endeavor to make it a truly effective instrument for lifting men everywhere to a higher standard of life and greater enjoyment of freedom.”

The radio broadcast sets the context: “History records many noble strivings towards the goal of freedom, justice, and peace. There have been many great declarations. Magna Carta in the year 1215. The Bill of Rights, 1689. The American Declaration of Independence, 1776. The French Declaration of the Rights of Man, 1789. Historic forward steps, but confined to specific countries and peoples. In 1948, the authors of the new document were agreed. The Declaration must be for all peoples.”

In April 1945, as World War II neared its end, President Franklin D. Roosevelt died suddenly, leaving a grieving nation and a world uncertain about what might follow. Just weeks later, on May 8, the war in Europe ended with Germany’s surrender. That summer, the United States dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in early August, leading to Japan’s surrender on August 15 and the official close of the war.

Amid both relief and horror, the United Nations Charter was signed on June 26, 1945, signaling the world’s intention to rebuild through peace and cooperation. But tensions were already rising between wartime allies, and the first Nuremberg Trials had begun that fall to reckon with atrocities committed during the Holocaust. Against this backdrop, the United Nations General Assembly convened for the first time in January 1946, and by spring, the newly formed Commission on Human Rights held its initial meetings. In just under a year, the world had gone from total war to an effort to define universal peace — and Eleanor Roosevelt, recently widowed and newly appointed, stepped into history as the chair of that commission, a role no woman had ever held before on the world stage.

As described in another UN radio production — 1949's Let Freedom Ring — the Universal Declaration, drafted by an international committee, was profoundly influenced by FDR’s 1941 State of the Union address, now known as the Four Freedoms speech. Delivered nearly a year before the United States entered World War II, Roosevelt outlined a vision of a world founded on four essential human freedoms: freedom of speech and expression, freedom of worship, freedom from want, and freedom from fear. These ideals would go on to shape the Atlantic Charter, the founding principles of the United Nations, and ultimately the Universal Declaration itself. In its preamble and thirty articles, the UDHR did something remarkable: it gave enduring form to principles that had long been expressed in revolutions, constitutions, and moral philosophies — but never before as a shared global commitment.

Images of the interim headquarters of the United Nations at Lake Success in the former Sperry Gyroscope facility, and a group of Japanese women looking at a Universal Declaration of Human Rights poster during their visit at U.N. interim headquarters in Lake Success (images courtesy of the UN media archive).

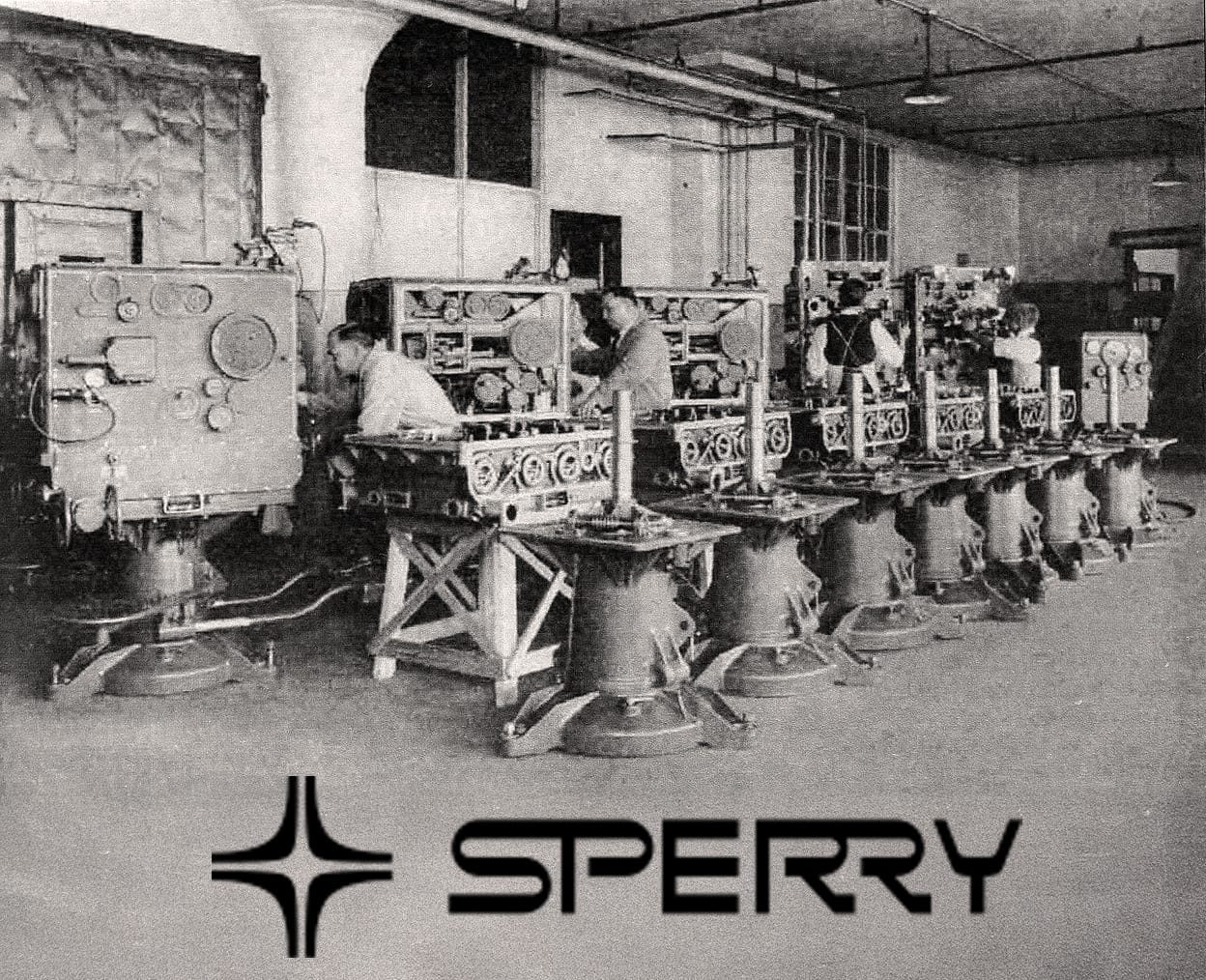

While browsing the UN’s media archive for historical images of the UDHR this week, I stumbled across a detail I had never known before: it turns out that the temporary headquarters of the United Nations, where the Declaration was first drafted and debated, was not located in one of the marble buildings or diplomatic enclaves we might associate with the UN today, but in a repurposed industrial facility — the former Sperry Gyroscope Company building in Lake Success, New York.

When the United Nations was established in 1945, it had no permanent home. While New York City was quickly chosen as the preferred location, it would take several years for the land to be secured and the new headquarters to be constructed along the East River. In the meantime, the UN needed a facility large enough to house its growing staff and operations. The former Sperry Gyroscope Company plant was selected because it was spacious, secure, and already outfitted with extensive communication infrastructure — thanks to its wartime role in producing precision guidance equipment. From 1946 to 1951, the building served as the UN’s temporary headquarters, hosting early General Assembly sessions, Security Council meetings, and the drafting of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

The symbolism was striking: a wartime manufacturing site converted into a place where the world would try to articulate peace. And more striking still, the Sperry family from Woodbridge’s early history is also the origin of this inventive branch of the Sperry family. Elmer Ambrose Sperry, inventor and founder of the company that developed gyroscopic guidance systems for naval and aerial warfare, was a direct descendant of Richard and Dennis Sperry, the 17th-century settlers who sheltered fugitive judges in a cave on West Rock.

The family’s story arcs across centuries — from colonial resistance to revolutionary technology — and somehow also touches the birthplace of modern human rights. Discovering this connection felt like a circle closing in real time.

Elmer Sperry was affected by motion, by instability, and instead of resisting it, he invented a way to respond to it — to remain oriented in a moving world. That’s not just a technical achievement; it’s a deeply human one. It resonates with the core aim of the UDHR and its moral gyroscope: not to eliminate motion, but to remain grounded in something durable while the world turns.

Elmer Sperry's family connection to Woodbridge (click to enlarge) and a photograph of his grandparents who relocated to NY from CT, Ambrose Lewis Sperry and Mary Brown Corwin Sperry (image courtesy of Sperry Romig).

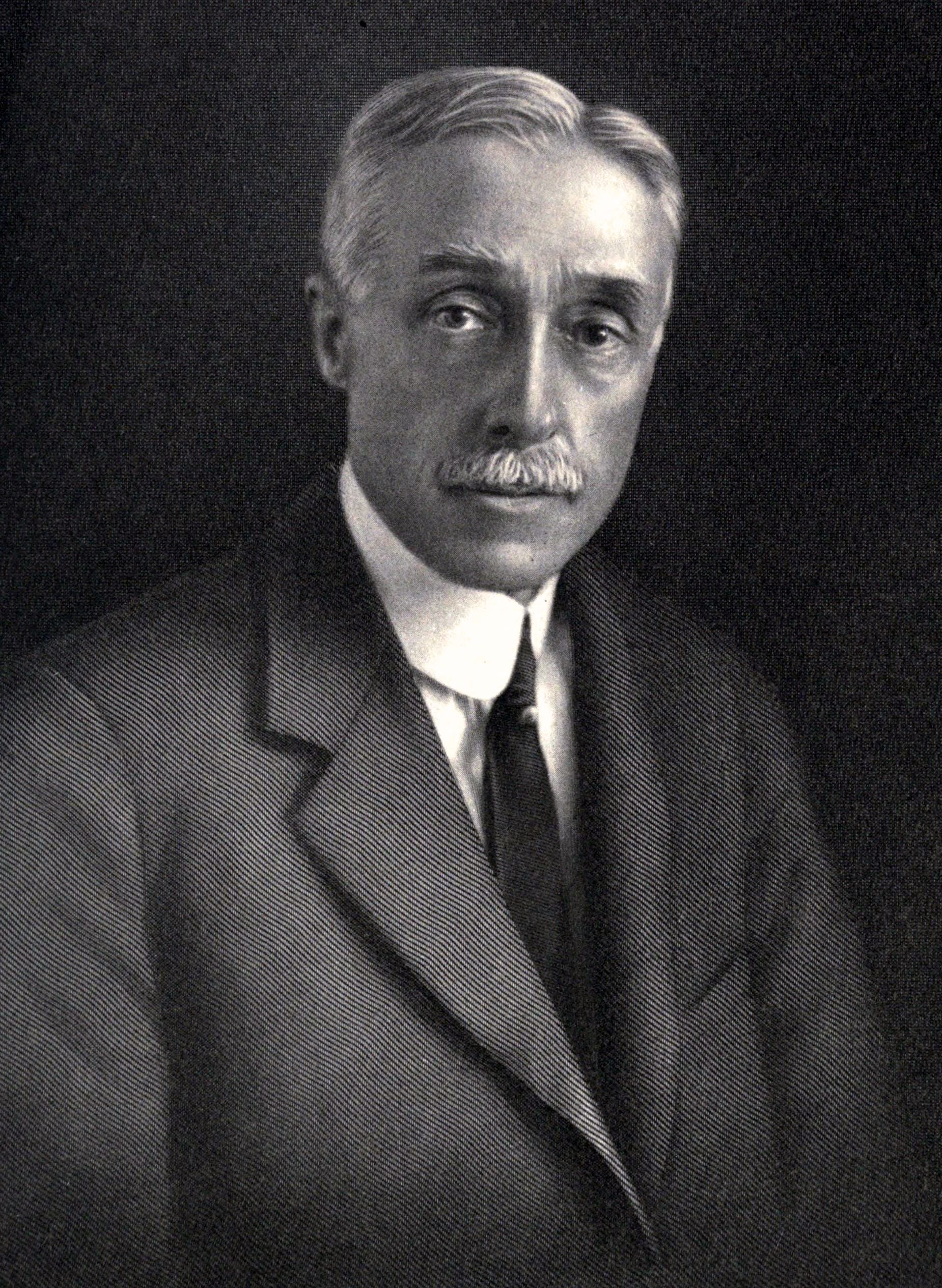

Elmer Ambrose Sperry (1860-1930) was born in Cincinnatus in upstate New York, under somber circumstances — his mother, Mary Burst Sperry, died the day after his birth. He was raised by his father Stephen DeCatur Sperry (1825-1889), and from an early age showed a remarkable talent for mechanics and innovation—traits shared by many in the Sperry family. His paternal grandparents, Ambrose Lewis Sperry and Mary Brown Corwin Sperry, had moved from Connecticut to the fertile farmland of upstate New York in the early 19th century, establishing a new branch of the family tree that Elmer would later make well-known.

After studies at the State Normal School in Cortland and a year at Cornell University, Elmer moved to Chicago and, by the age of 20, had founded the Sperry Electric Company. His early inventions improved safety in coal mines and efficiency in electric railways, and he played a formative role in the development of electric automobiles and portable lead-acid batteries. In 1896, he drove one of his electric cars through the streets of Paris — the first American-made car to do so.

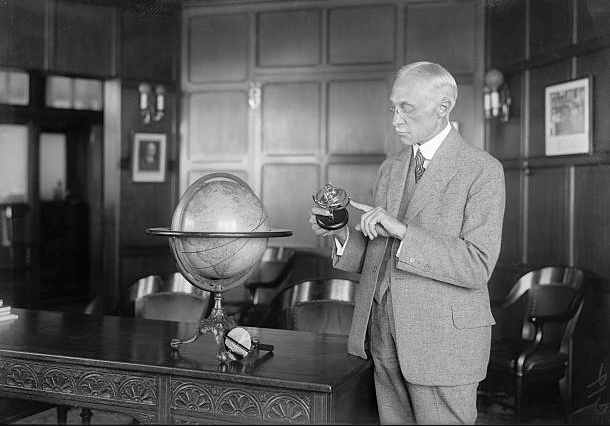

Elmer Ambrose Sperry (images in the public domain).

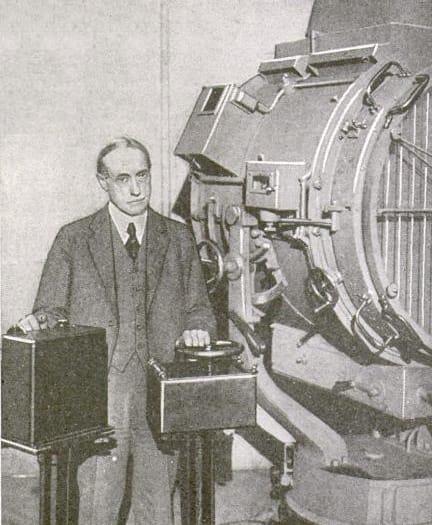

Sperry’s defining breakthrough came not from industry, but from seasickness. After an uncomfortable Atlantic crossing in 1898, he began experimenting with gyroscopes to stabilize ships at sea. His early designs used internal sensors to counteract rolling waves — a precursor to modern automatic stabilization systems. In 1911, the U.S. Navy began integrating Sperry’s gyroscopic stabilizer into its ships. Though the technology was too costly to deploy widely, Sperry's work forever changed how we think about guidance, balance, and motion.

Elmer's legacy was carried forward by his son, Lawrence Burst Sperry (1892-1923), a brilliant inventor in his own right. By his early twenties, Lawrence had already developed the first practical autopilot system for airplanes, a breakthrough that earned him international acclaim and the prestigious Aero Club of France award. His innovations in aircraft stability and safety helped lay the foundation for modern flight control systems. But his life was tragically short. In 1923, while piloting a flight over the English Channel in poor weather, Lawrence’s plane disappeared. His body was later found in the water. He was just 31 years old. Though his career was brief, the tools he created for navigating turbulence — both literal and technological — continue to guide us today.

Elmer's son, Laurence Burst Sperry (images in the public domain)

By 1955, the Sperry Corporation had merged with Remington Rand to form Sperry Rand, expanding into computing and office technology. The company developed early commercial computers, including the UNIVAC, and played a competitive role alongside IBM during the early decades of the digital age. In 1986, Sperry was acquired by the Burroughs Corporation, and the two were combined to form Unisys, the global information technology company that still exists today. Though the Sperry name faded from corporate signage, its legacy still guides both machines and ideas.

From an old Woodbridge family name tied to motion and balance to a global document charting human dignity, the threads between past and present continue to reveal themselves. Perhaps this is more than a coincidence of locations and surnames — perhaps it’s a quiet reminder that the ideals behind the UDHR were always meant to be both universal and personal. Not distant abstractions, but commitments to live by.

Even now, news headlines echo the very injustices this Declaration sought to prevent: the persecution of minorities, the silencing of speech, political imprisonment without trial, refugees denied refuge. Looking back to the 1940s from where we stand today, the UDHR doesn’t feel like a closed chapter — it reads like a message addressed to us, written not to decorate the past, but to instruct the present. And it seems to ask something of us still.

We are currently in the 77th year since the UDHR was proclaimed. But as the 1973 radio broadcast stated “…we are still too far from a world in which human rights are universally observed by individuals and protected by governments. …Human rights, in the words of the Universal Declaration, are inherent. They are vested in and belong to the nature of man. No external authority — no government, however benevolent — can grant and assure these rights."

The broadcast concludes by quoting Mahatma Gandhi: "The true source of rights is duty. If we all discharge our duties, rights will not be far to seek. If, leaving duties unperformed, we run after rights, they will escape us like a will-o'-the-wisp. The more we pursue them, the farther will they fly."