Reading the Sky — A Look Back at How We Met Winter Storms

As we brace for a winter storm forecast to be a blizzard, news alerts pulse and social media posts circulate snowfall projections in increasingly urgent tones. There is talk of wind gusts and whiteout conditions, of historic potential and travel advisories. We make the familiar run to the grocery store for bread and milk.

But harsh winter storms are not new to our small-town communities.

Long before radar loops and forecast models, families in Woodbridge and Bethany read the sky, watched the wind, and prepared accordingly. Today, as I ready my own home for the coming storm, I find myself thinking back to what my grand-aunt, Hazel Lounsbury Hoppe, recounted about winters past in her books Pebbles and Flowers and Bethany Yesterday: The One Room Schools, both devoted to preserving our local history.

Reading the Sky

In the days before high-tech forecasts and apps, the signal was physical — a weather vane fixed to a barn cupola raised by local hands, the color of the sky, and a practiced eye trained by seasons to know what a wind shifting east would bring. The infrastructure of prediction was as tangible as the buildings themselves — simple, visible, and human-scaled.

In Pebbles and Flowers, Hazel wrote:

“We managed to deal with the weather changes without today’s expert advice. I think the old Yankees would have scorned the weather charts and maps showing air currents and wind velocity and storms in the offing. Just about every farm in town displayed a weather vane on the roof of one of the barns, and the old-timers forecasted their own weather with this useful object by noting the changes in wind direction. I remember my father stepping outside and focusing his eyes on the sky and weather vane. He could tell when rain was coming, he could identify fair weather clouds, and he always knew that wind shifting to the east forecasted stormy weather.

Since agriculture was the main occupation during those years, forecasting the weather was a necessary skill, for Mother Nature played an essential role in the planting and harvesting seasons.”

Delivering Through the Winter Snow

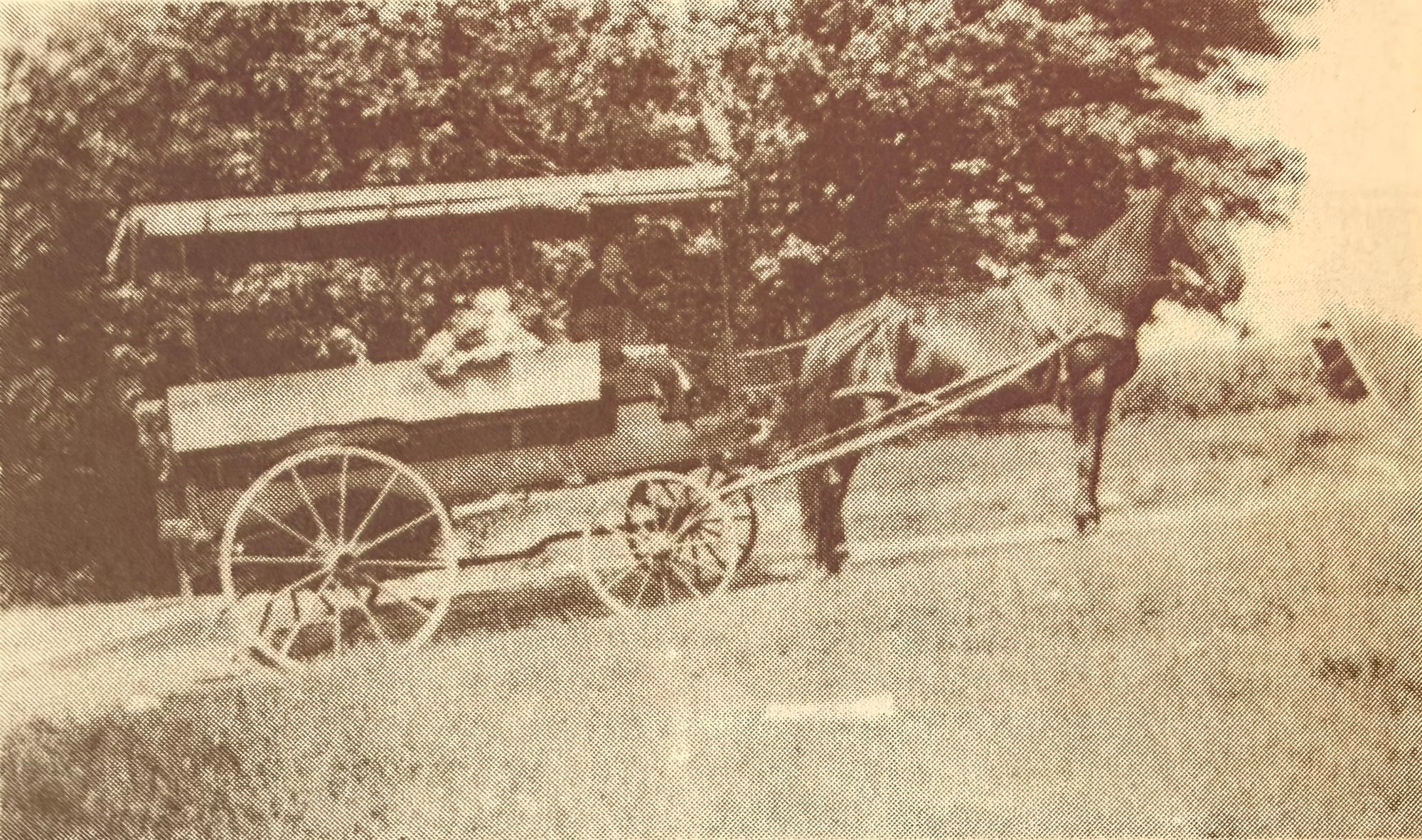

Today we head to the grocery store to stock up on staples before the storm. A century ago, people could count on their local farmers who continued to deliver milk door to door through winter weather. When snow made roads impassable for wagon wheels, the sled was hitched to the usual team of horses, and milk was delivered as always.

Again from the pages of Pebbles and Flowers, Hazel wrote:

“Winter snows brought out the sleighs and box sleds when the roads became impossible for the wheels to navigate. My mother had memories of those times around the turn of the century. Her father, Jerome Downs, operated a milk delivery service from the family farm, serving customers in New Haven homes. In those days the dairy farmer would carry tall cans of milk in the back of a sled, which consisted of a large box-like wooden body placed upon runners. The driver occupied the one seat up front and Mama and her sister would sit in the back among the milk cans and ride the route with their father. When grandfather arrived with the milk, the lady of the house would come out with a quart pitcher and grandpa would dip out the milk and pour it into the container. Unpasteurized, unhomogenized, plain old milk — life was so simple in those days.”

Horse-Drawn School Transportation

Long before yellow school buses, town transportation existed — it simply looked different. And this mode of getting children to school also adapted to meet the challenges of the harsh winters. The cold itself was remembered plainly.

In Bethany Yesterday: The One Room Schools Hazel wrote:

“By the early twenties, there was a definite trend toward the general transportation of school pupils; although the school bus had not come upon the scene, the horse and buggy was put to good use. ...

My mother and father transported children to Beecher School for a period of about two years, starting around the spring of 1925. We had a chestnut colored horse named Prince and a two-seated surrey with a fringe on top, and besides three of us Lounsbury’s, we carried the Harrison boys, and for a short time Dorothy Hewins Kusterer and Everett Keeler and our cousin, Jerry Downs.

...

When the weather was cold or rainy, the trip to school in the surrey was not very pleasant. There were black curtains made of a type of heavy oilcloth that snapped around the outside of the carriage, and even though the interior was gloomy, at least it was dry and a little warmer. In the bitterest of the cold weather, nothing kept us warm, not the long winter underwear tucked into our long stockings and down into our high shoes, nor the heavy buffalo robe which was a standard accessory. The buffalo robe was a family inheritance, and was evidently the skin of a real buffalo, grayish white long fur, perhaps six feet square, lined with red plaid woolen cloth. I can remember riding home from school in the open wagon on the coldest of January days, when the air was so sharp it was difficult to breathe, and we would have to take refuge with our heads under the buffalo robe. Even though the scratchy woolen lining was uncomfortable upon our faces, it was preferable to the biting wind on the outside.”

Getting Home Through the Snow

Winter travel — then as now — did not always go as planned. In Bethany Yesterday, Hazel recounted one snowy journey home from school that began like any other and ended memorably.

“Elbert N. Downs tells of a memorable trip home from school in the winter of his fourth grade at Beecher School. The snow had been falling during the day, so that when it was time for dismissal, it was evident that the roads were a bit slippery. The regular driver, feeling a bit under the weather, had sent his housekeeper in his place to pick up the children in the two-seated sleigh. All went well in the beginning of the journey, but as the sleigh filled with children came down Hatfield Hill Road in the vicinity of the dam at Bethany Lake, the vehicle slipped in the soft snow and turned over, tossing all the occupants abruptly into the snowbanks. The youngsters scrambled out of the snow, unharmed, but the housekeeper, a rather hefty woman, had fallen in such a way that she was injured. The children performed the necessary task of turning the sleigh upright, for they were accustomed to all sort of responsibility in those days. However, no matter how they tried, they could not help the unfortunate housekeeper back into the sleigh. It became a problem indeed. Luckily, along came the Tudor Baker on his route through town, and seeing the youngster’s plight, he stopped to help. With the aid of this good samaritan, the woman was lifted into the back of the sleigh, and young Ellie volunteered to drive the horse the rest of the way home.

Along they went, rounding the curve in the road at the eastern end of the lake, then onward due north and around the next curve. The steep hill ahead of them would crest and lead down another steep hill to Downs Road. As the horse got half-way up the hillside, his steps began to lag, for the filled sleigh was heavy, and the road underfoot treacherous. Ellie knew that this was the time to use the whip, just for a touch, to encourage the lagging animal. However, the light touch on the flank surprised old dobbin, and he gave a leap which, in turn, surprised all concerned, for as the sleigh jolted forward, out of the back of the vehicle catapulted the hefty housekeeper, once more to land in the snow filled road!

Young Ellie decided it was time to give up a losing battle, so, leaving the ill-fated woman reposing in the snow, he drove on homeward to find his father for aid in the perplexing situation. Our friend, the housekeeper, had to be carried into New Haven to the hospital where a broken bone was found and treated.”

As we wait for tonight’s storm to arrive, it is worth remembering that winter has long shaped life here — not with spectacle, but with steadiness. The wind shifts. The snow falls. And our small towns adjust, as they always have.