Uncovering some Amity history: How we arrived at a 7-4-2 regional school board

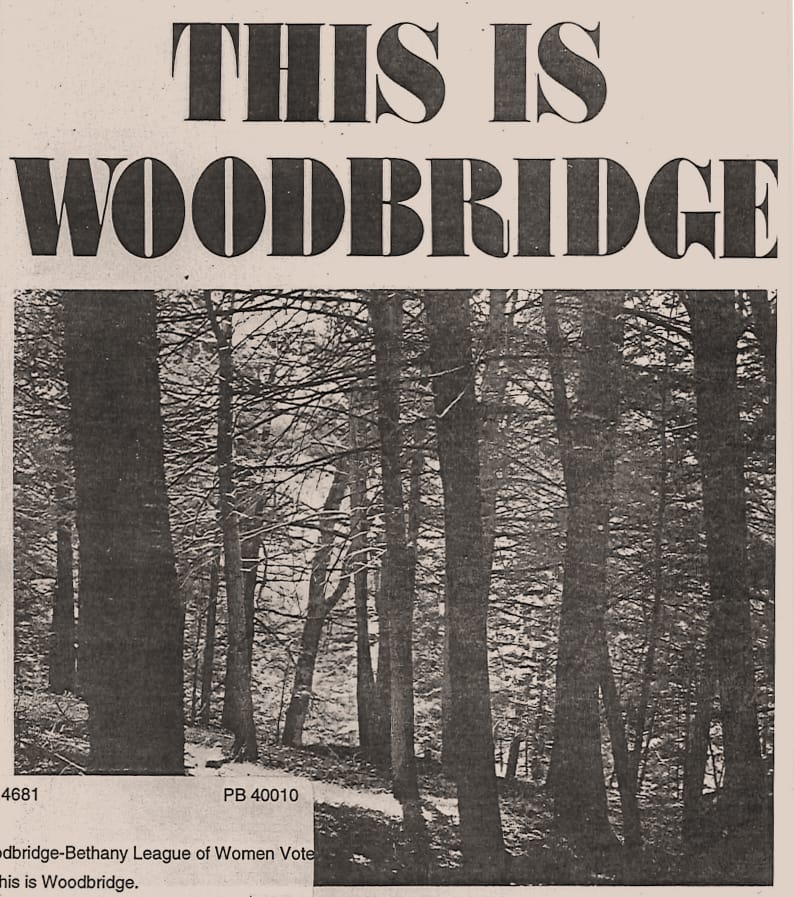

A few weeks ago, as I paged through a folder of town history original source materials gathered over the years, I came across a copy of our local League of Women Voters's 1973 booklet, This is Woodbridge. Acting as a kind of time capsule, it provided a view of our little town more than fifty years ago — and among its pages overviewing town governance and civic life, it offered a surprising detail regarding the early-1970s structure of the Amity Regional School District.

The 1973 booklet revealed that at that time the Region 5 Board of Education was a nine-member board, composed of three members each from the towns of the district: Orange, Woodbridge, and Bethany. Digging into the past a bit further, it became apparent that this simple, equal structure had persisted since the district's founding. While the 1973 publication provided this helpful benchmark, it also raised the key question: if the original board structure was equal, when and why did it change?

I had a personal interest in this question as I served as a member of the Amity Regional Board of Education from 2014 to 2021. Despite that experience, I was not aware of the details of how the Board came to operate under the current 7-4-2 structure — seven members from Orange, four from Woodbridge, and two from Bethany.

So the discovery of the clues from 1973 set me on a journey through town records in the Town Clerk's vault, other League of Women Voters artifacts, and eventually to court documents. I found pieces of the puzzle that together tell a remarkable story of how the Amity Board came to be shaped by both democratic ideals and federal mandates. And the history of this transformation may be relevant today as our towns consider new questions of cost, governance, and collaboration.

In an earlier summary of a circa 1954 publication, titled Bethany Is Your Town, the League of Women Voters documented the formation of the Amity Regional School District. At the time, the district was described as being brand new — created in response to New Haven's decision to stop accepting out-of-town junior high students. The League's summary conveys the urgency and ambition of the moment, as well as the inter-town cooperation that made the district possible. Their words remain a valuable primary source for understanding the origins of Amity, and the central role it once played in supervising education in the three towns' elementary grades as well. After a recounting of elementary grades in Bethany, the League noted:

“The problem of providing junior and senior high school education still remained to be solved, since New Haven notified the town that Bethany children could not be accommodated in the Junior High Schools after September of 1953. In 1950 studies were begun with Woodbridge and Orange for a Regional High School. A Regional Board with three representatives from each town was established on March 6, 1953, following the approval of the Regional District by separate referendums in the three towns. The junior unit opened in September of 1954, and the senior unit will be ready for September of 1955. The Regional Board voted to accept responsibility for grades seven through twelve as of September, 1954.

The present superintendent was supplied by the State at the request of the Regional Board, and he is supervisor not only of the Regional School but also of the elementary schools of the three towns. The budget of the Regional School is set up by the Regional Board after a public hearing and may not be changed by the separate towns.”

This early Amity chapter of the League of Women Voters played a vital role in informing citizens and fostering productive civic deliberation on issues just like this. It’s no exaggeration to say that they helped shape the very framework of regional education in our area. While the League's visibility has diminished in recent years, the civic values it embodied remain as relevant as ever — perhaps even overdue for revival, should a new generation of residents wish to take up that mantle. (As an aside: if you're interested in learning more, or getting involved with the league, please visit the LWV-Amity page — a small group of us recently gathered for lunch and as always, we would welcome newcomers and 'old timers' alike.)

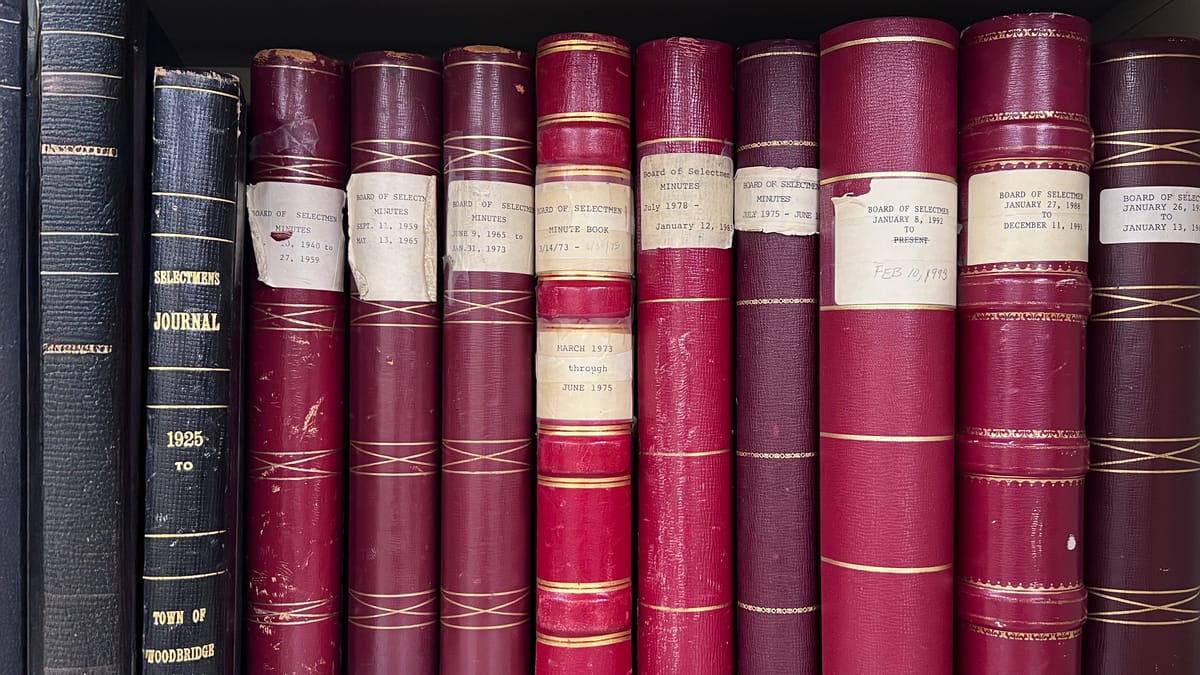

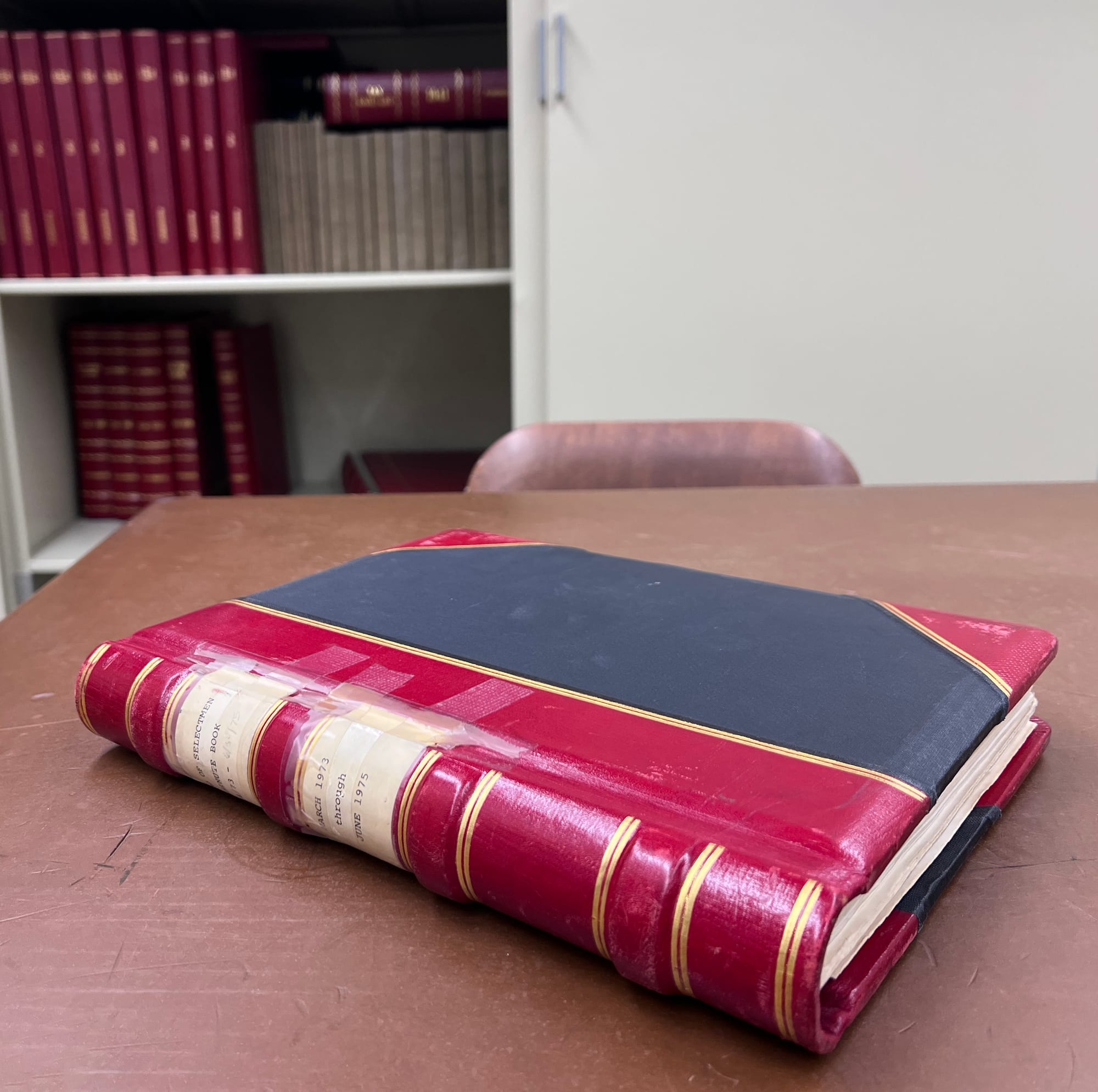

Earlier this week when I stopped by the Town Clerk's vault in the lower level of Woodbridge Town Hall, I was looking for unrelated archival materials. But while browsing bound volumes of Selectmen’s meeting minutes from the mid-1970s, I stumbled upon details of what seemed to be rather intense debates surrounding Amity board representation.

As I turned through the pages of the record book I had selected from the middle of the top shelf of Selectmen's Records of this era, events from 1973 through 1975 unfolded before me. This began as routine mention of the appointment process for the regional board members (in a nutshell, it seems a nominating committee appointed by the Selectmen chose a candidate whose name was then voted upon by the Selectmen to be presented at the Annual Town Meeting for formal action to appoint). This soon escalated into discussion of legal action, governance debates, and efforts to rebalance power within the Amity Regional School District.

I pulled out my phone and snapped photos of a few pages... which quickly turned into a set of 35 images capturing details related to the Amity Regional District. Paging through this collection, here's a summary of what I found:

1973-1975: Amity matters before the Board of Selectmen

On March 21, 1973, the Woodbridge Board of Selectmen appointed a four-member Nominating Committee — Russell B. Stoddard (R), Virginia S. Goodrich (R), Jerome L. Weinstein (Unaffiliated), and Edward B. Winnick (D) — to select a candidate for the Amity Regional Board of Education. Their recommendation was due by May 15, 1973, as required under Section 8-16 of the Town Charter.

On May 5, First Selectman Ralph Capecelatro of Orange submitted a letter referencing a study on the Amity School District. The letter was acknowledged at the May 9 meeting but did not trigger any immediate action. Shortly after, on May 14, Virginia Goodrich resigned from the Nominating Committee, and Carol Hart was appointed in her place.

By May 21, political momentum had shifted. The Selectman noted that the Governor would soon sign a bill authorizing the election of regional school board representatives. The Board then unanimously voted to request the Amity Board of Education move its Annual Meeting to the first Tuesday in May to align with the proposed election date. A letter from Orange First Selectman later supported this change on July 18, as acknowledged in the August 8 meeting.

As the calendar page turned to 1974, the question of governance intensified. On March 14, a new Nominating Committee — Joseph Calistro (R), Edward Winnick (D), and Jerome Weinstein (U) — was appointed to propose a Board candidate by May 14, with a vote to follow at the Annual Town Meeting on June 3, 1974. But this time, legal guidance was sought and received at the March 25 meeting, affirming that such elections could be validated by legislative action if needed.

~~~

I would later learn that between these meetings, a lawsuit had been filed by residents of Orange challenging the equal representation structure of the Amity Regional Board — arguing it violated the "one person, one vote" principle under the Equal Protection Clause. The U.S. District Court agreed, declaring the apportionment unconstitutional due to vote dilution in Orange. This decision was affirmed by the Second Circuit Court of Appeals. But more on this lawsuit, later.

~~~

Tensions appeared to come to a head on April 24, 1974, when the Board of Selectmen voted to authorize Town Counsel to intervene in Civil Action N-74-75, John E. Baker et al. vs. Regional High School District #5 et al., marking Woodbridge’s formal entry into a lawsuit involving all three Amity towns.

The political atmosphere grew more serious in the Spring of 1974. At the regular May 9 meeting after Leonard Lohne was named the Woodbridge candidate for the Regional Board — evidently following the usual appointment process — the Board turned its attention to a letter it received from the Democratic Town Committee urging that the relationship of the Town of Woodbridge to the Amity Regional District be examined. The Selectmen called for a Special Meeting to take place May 22 and at this meeting, the Board of Selectmen passed the following resolution, establishing a committee to consider restructuring or exiting the district:

RESOLUTION — SPECIAL STUDY COMMITTEE RE: REGIONAL SCHOOL SYSTEM AMITY DISTRICT #5

RESOLVED THAT: There is hereby created a special study committee consisting of Nine (9) members to be appointed by and serve at the pleasure of the Board of Selectmen, having the following purposes and duties:

1. To prepare a report to be submitted in writing to the Board of Selectmen of all the feasible alternatives to Amity Regional District No. 5, as presently constituted, available to the Town of Woodbridge to satisfy its statutory obligations to educate its grades 7–12 resident pupils.

2. Said alternatives shall include but not be limited to:

a. The dissolution of the District;

b. The creation of a District consisting of Bethany and Woodbridge;

c. The withdrawal of one or more grades;

d. The amendment of the present plan of the District in which Orange has a majority of the members of the Board of Education;

e. The amendment set forth in (d) supra, with a change in assessing the net expenses against the Grand List of the member Towns combined in lieu of a cost per pupil basis.

3. To report with respect to each alternative:

a. The cost of education to Woodbridge;

b. The cost of implementation of the plan, including dissolution under the statutes;

c. The effect upon the curriculum and the quality of education;

d. The legal procedures required, including but not limited to amendment under Section 10–47c and Legislative amendments as required;

e. An estimate of the timetable required to implement the plan.

4. To report specifically the percentage of the general revenues of each of the present member Towns expended as its share of the net expenses of the present District; and, to recommend a formula for assessing the net expenses of the District against the combined Grand Lists of the present member Towns. In this connection, recommend the amendments to the present statutes required by such a formula.

5. To present within Two (2) weeks of its appointment an estimate of the cost, if any, of expert advice deemed to be required to accomplish the purposes and perform the duties hereinbefore set forth.

By December 1974, the Study Committee, chaired by Town Attorney William J. Cousins, issued a detailed report. Among its six options were maintaining the current system, modifying board composition, or withdrawing from the district. Concerns over judicial rulings — particularly those by Judge Newman who was hearing the case — were front and center in terms of discussion that followed. Some advocated legislative fixes; others pushed for a district-wide tri-town committee. The December 11 meeting revealed just how politically fraught the situation had become as arguments in the Baker lawsuit advanced toward federal judgment. (The U.S. District Court would ultimately rule the following year that the district’s existing structure was indeed unconstitutional.) As 1974 drew to a close, the Board acted:

Page 552–553 — Meeting Date: December 18, 1974

After learning that the Amity Board had decided to appeal Judge Newman’s decision, the Board of Selectmen voted:

MOTION: Given that the Amity Board has decided to appeal Judge Newman’s decision, the Board of Selectmen authorize Town Counsel to join that appeal representing the Town Treasurer and Town Clerk for the purpose of representing and protecting the Town’s interests. (Calabresi–Scherr)

VOTE: Unanimous in favor

As the calendar turned to 1975, routine governance resumed — but under a shadow of uncertainty. On March 20, party leaders were asked to submit names for a new Nominating Committee. That committee — Fred Moss (R), Allen Duffy (D), and Jerome Weinstein (U) — was confirmed on March 27.

By May 14, they had nominated Bette Gruskay (also referred to in the records in the style of time, as Mrs. Frank Gruskay) to continue her service as one of Woodbridge's three members of the Board of Education, revealing that the chapter of upheaval, lawsuits, and legislative uncertainty captured in this particular record book had ended in stalemate, as the Town awaited the outcome of the court proceedings still to come.

Returning from my vault visit, I found myself going further down the rabbit hole as I dug deeper into the history of this episode. As the Selectmen had been deliberating and acting in Woodbridge, the Connecticut General Assembly meanwhile had passed legislation that went into effect in July 1975 as Public Act 75-644. It required all regional districts to adopt constitutionally compliant apportionment, and establishing procedures for this process. Amity's District Reapportionment Committee (DRC) would begin this process soon after to propose a new apportionment plan.

Skipping ahead a bit in the chronology, additional online sleuthing revealed that after a few more years of deliberation, public meetings, and committee reports, the court delivered a second, final ruling, in the case. Taken together, the rulings in Baker v. Regional High School District No. 5 appear to have resulted in two major court decisions that reshaped regional school governance in Connecticut. At issue were another series of events that had unfolded:

1976–1977: The 3-3-3 Residency Plan

District No. 5's DRC proposed a plan where all nine Board members would be elected at large, but with a residency requirement of three members from each town. On October 7, 1976, the DRC voted to “recommend the following plan ("the 3-3-3 plan") to the State Board of Education: The District No. 5 Regional School Board of Education shall be composed of nine (9) members elected at large. Of the nine (9) members, three (3) are to be residents of Bethany; three (3) are to be residents of Woodbridge; three (3) are to be residents of Orange. Each member is to have one vote.”

Apparently, the thinking at the time was that the plan's residency requirement plus districtwide voting would lead to the election of Board members focused on representing all three communities' needs rather than only those of the towns where they reside. It should be noted however that the Woodbridge and Bethany members of the DRC voted for this plan; the members from Orange voted against it. With a majority in favor, the plan could proceed to referendum.

But before this plan got to voters for a decision, the State Board of Education rejected it on December 7, 1976, citing concerns over compliance with federal constitutional standards. Subsequently, the U.S. District Court reviewed the plan and, in a 1977 decision, held that it satisfied constitutional requirements.

On January 5, 1977, intervenors from Woodbridge and Bethany filed objections to the State Board's decision and both intervenors and plaintiffs “agreed to submit to the Court the question of the constitutionality of the apportionment plan adopted by the DRC, but rejected by the State Board of Education. In addition, counsel have submitted briefs on the constitutionality of an apportionment plan based on weighted voting.” On May 20, 1977 the U.S. District Court would issue a memorandum decision in Baker v. Regional High School District No. 5, 432 F. Supp. 535. In it, Judge Jon O. Newman overseeing the case opined:

“Perhaps the plan will influence a new alignment of political forces in the District and encourage candidates for the Board of Education to fashion regional, rather than town, constituencies. If so, then the plan will not only have passed constitutional muster, it will have also contributed to the development of a healthy atmosphere for the resolution of regional public education issues in District No. 5. Since this Court concludes that the 3-3-3 plan on its face is consistent with the one person-one vote standards of the Fourteenth Amendment, plaintiffs' motion to impose weighted voting as interim relief must be denied.”

But when the plan was submitted to voters at a districtwide referendum held on January 17, 1978, the 3-3-3 Residency Plan was rejected. So the matter of Amity reapportionment went back to the drawing board!

1978-1979: The 7-4-2 and Safeguard Plan

Following the rejection by voters, the DRC developed a new plan expanding the Board to 13 members. Known as the '7-4-2 Plan' it gave Orange seven seats, Woodbridge four, and Bethany two, reflecting population proportions. It also included a safeguard to prevent any single bloc from holding majority control, prohibiting the Board from taking action based solely on a majority made up entirely of members from either Orange or from the combined delegation of Bethany and Woodbridge.

Ultimately, the State Board of Education approved the 7-4-2 Plan, and it was ratified by voters on September 25, 1978.

In the last chapter of the saga, in 1979 intervenors from Woodbridge and Bethany sought a judicial declaration that the 7-4-2 Plan was constitutional, with plaintiffs expressing concerns about the majority action limitation. On September 12, 1979, the court reviewed this plan and although Judge Newman declined to issue a declaratory judgment on the plan’s constitutionality, he wrote in Baker v. Regional High School Dist. No. 5, 476 F. Supp. 319:

"While the proposed plan is novel, its structure does not on its face offend constitutional principles. Future judicial review may be appropriate should its implementation prove inequitable in practice."

He also noted:

“Should the Plan's majority limitation provision lead to the constant frustration of the same majority of members present and voting, whether that majority were composed of the representatives of Orange, or the representatives of Woodbridge and Bethany, invalidation on constitutional grounds might well follow.”

The legal journey of the Amity Regional School District No. 5 highlights the complexities of ensuring equitable representation in regional governance structures. The evolution from equal town representation to a proportionally representative model — with checks on majority power — reflects efforts to balance population disparities with fair governance. Throughout, the courts have played a pivotal role in scrutinizing these plans to ensure compliance with constitutional mandates.

Understanding the legal and civic history of Amity’s governance is more than an academic exercise. It reveals the deep roots of today’s conversations about fairness, representation, and cost sharing. As we face new decisions about infrastructure, budgets, and possibly even K–12 regionalization, remembering how we got here can help inform where we might go next.