When ‘That Great Sperry Family’ finds its way back to Woodbridge

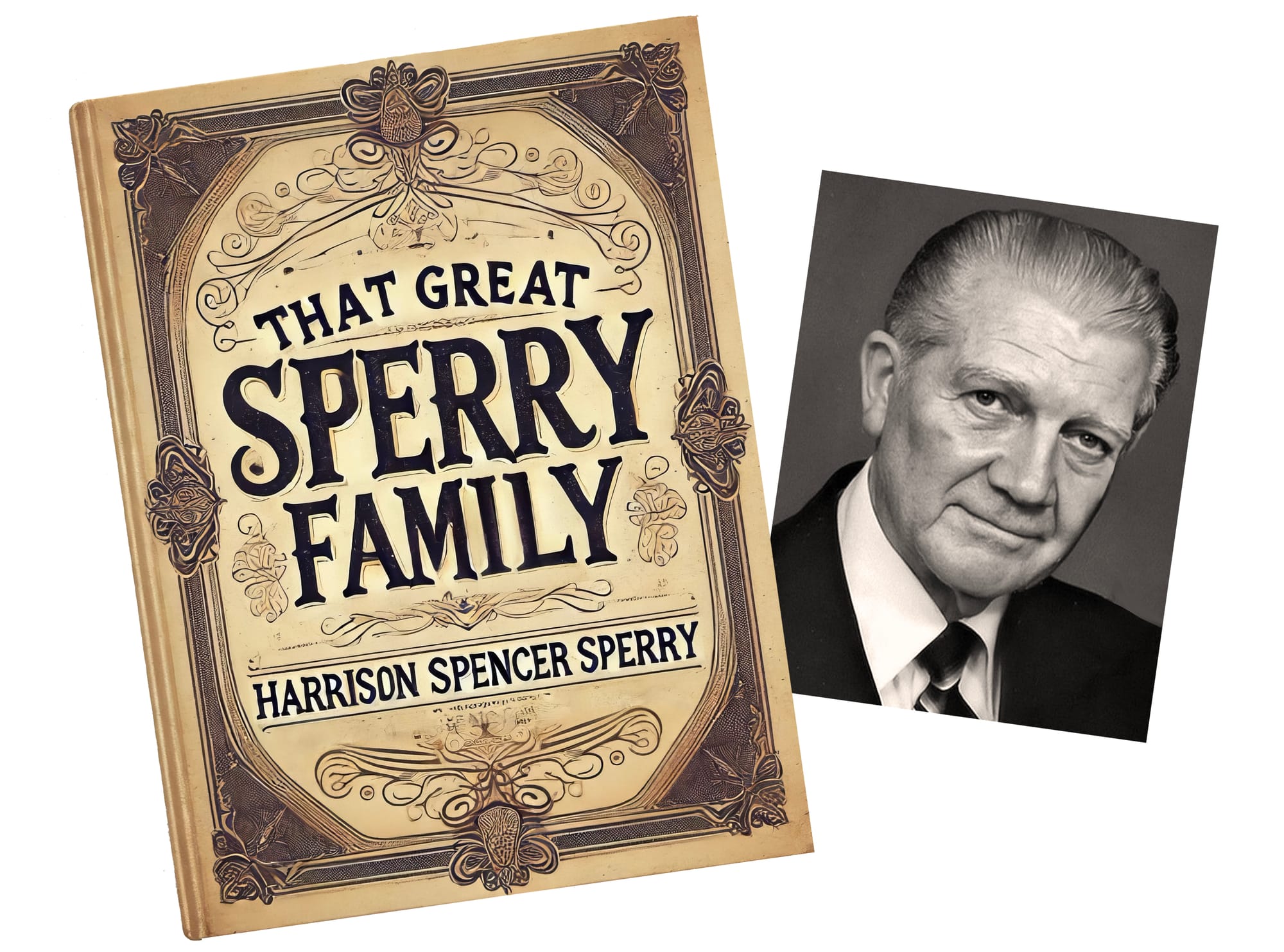

Many years ago, Harrison Spencer Sperry (1912-1994) meticulously compiled his genealogy research into a 159-page manuscript he titled ‘That Great Sperry Family.’ Just the other day, some far-flung members of the family paid a visit to Woodbridge to learn more about their roots. As avid readers of 'TownHistory' might guess — there's a tale to tell.

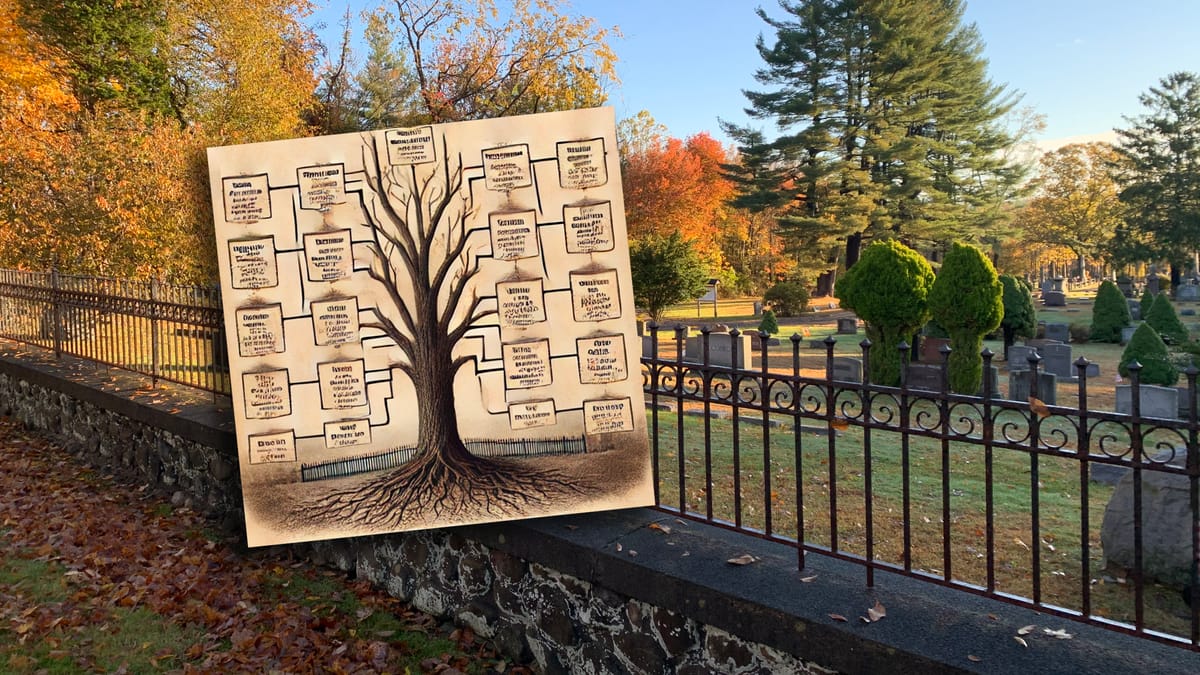

Let's begin where the Sperry family story starts: Richard Sperry (1606-1698) and his wife Dennis Sperry (1624-1707) settled in the area of the New Haven Colony that later became the town of Woodbridge in the 1640s. This couple, who had 10 children born between 1649 and 1668, are said to be the ancestors of everyone with the surname Sperry in North America.

Richard was born in Thurleigh Parish, in Bedfordshire, England and is thought to have come to Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1637 on the ship Hector of London with Theophilus Eaton and John Davenport and was among the group that left Massachusetts the next year to found the colony in New Haven, where he worked as a farmer for Deputy Governor Stephen Goodyear (1598-1658). Richard became a freeman in 1644 and was married in New Haven in 1647 to a woman named Dennis — an unusual spelling of Denise — who was born in Monkleigh Parish, in Devon, England. Family tradition holds that she may have been Stephen Goodyear's daughter, but there are no existing records to confirm this. However, we do know that from Goodyear, Richard acquired a large tract of land described as “the rich plain of West Rock” consisting of over 1,200 acres, and this is the area that became known as ‘Sperry Farms’ in Woodbridge.

By the early 166os, it was said that “Richard’s house was one of two between New Haven and the Hudson River in New York, except a few in Derby.” It is likely that the other house mentioned was that of Ralph and Alice Lines who lived at the top of Chestnut Hill (near the present-day Park Lane, overlooking the present-day Amity Road).

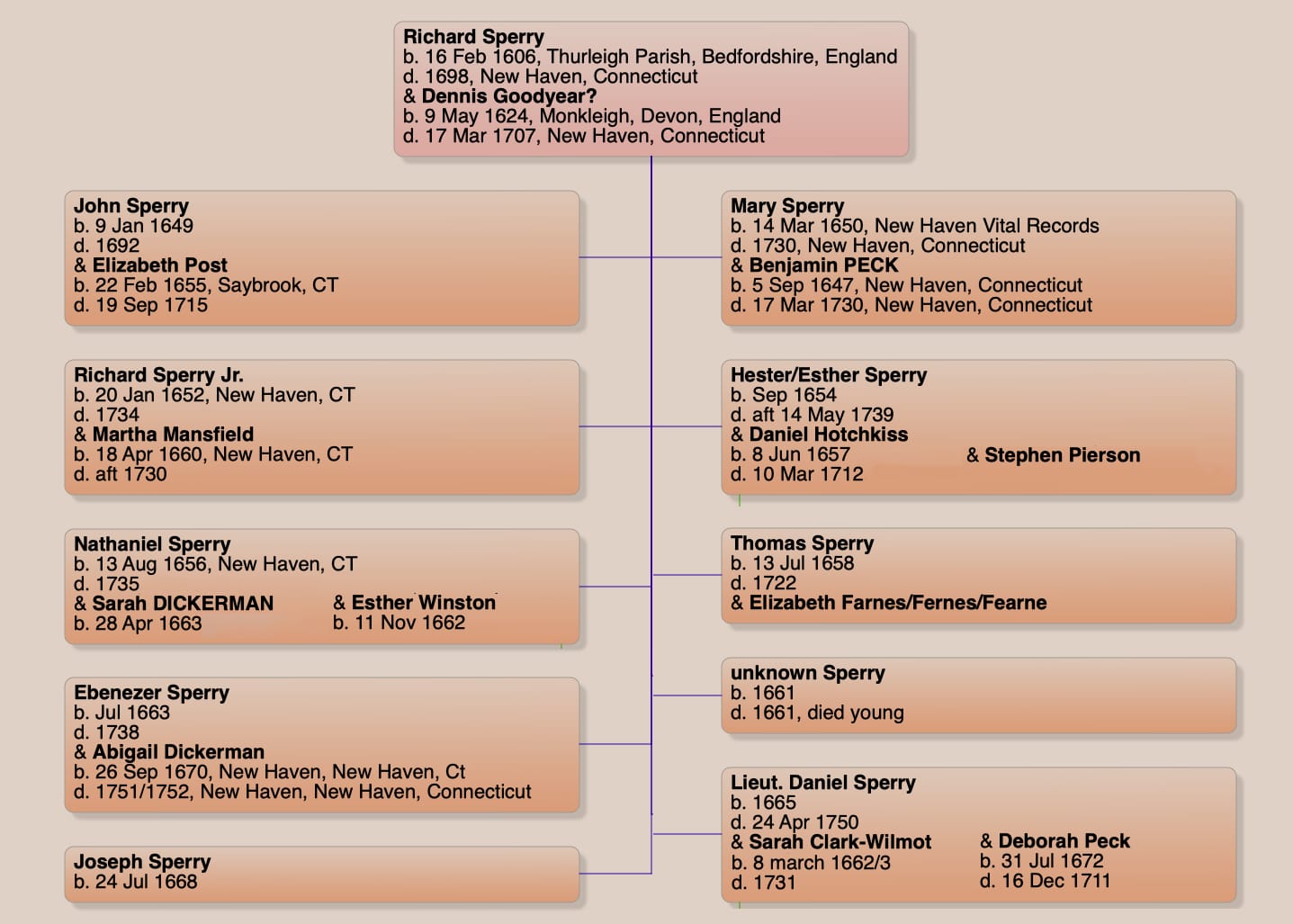

Beginning in May of 1661, Richard and members of his family were known to have “harbored the regicides," Edward Whalley and William Goffe. These were two of the so-called Three Judges (the third was John Dixwell) who arrived in New Haven while on the run from King Charles II. Restored to the throne in 1660 after the failure of the Commonwealth government, Charles II was intent on pursuing the men who signed his father King Charles I's death warrant in 1649.

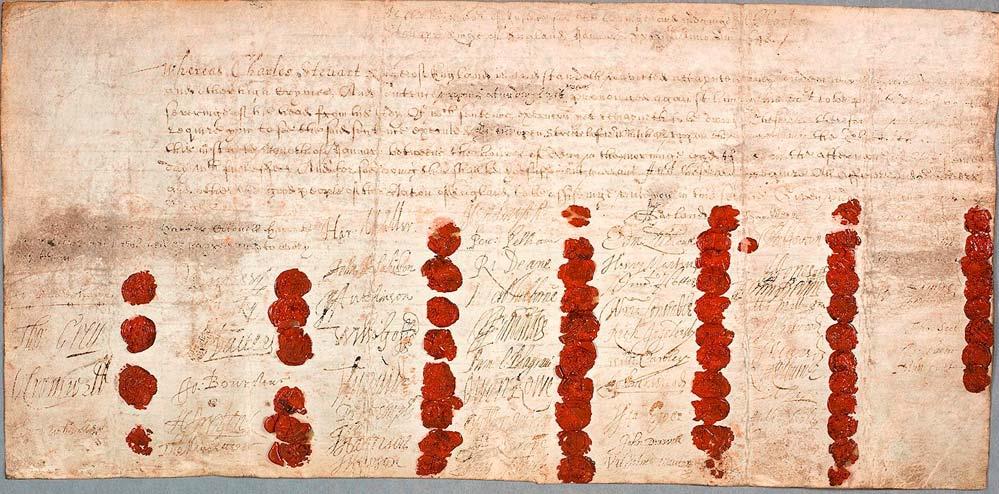

After their arrival in the New Haven Colony, Richard Sperry hid Whalley and Goffe on his land at West Rock in a cave now known as the Judge’s Cave. The Yale president Ezra Stiles (1727-1795) who would have been a contemporary of some of the grandchildren of Richard and Dennis Sperry, recounted the story in his book ‘A History of the Three Judges of King Charles I’ published in 1794.

“Richard Sperry provided them with basins of food, which were carried to a stump at the foot of the hill. When his small sons, who carried the food there, wondered that the basins always vanished and then reappeared empty, the farmer said that someone was working in the woods.

One night, frightened by a wild animal, Whalley and Goffe went to Richard’s house and were hidden there for a while. The house was built on an island, surrounded by a Morrass, with a causeway leading to the main road; a moated manor. While the judges were there, the King’s officers, who were looking for them everywhere and had some way gained a clue as to their whereabouts, appeared in sight. But, owing to the peculiar position of the house, the regicides were able to escape.

Those who harbored Whalley and Goffe were in danger themselves. By law they were under the same condemnation as traitors – subject to being hanged, drawn, and quartered alive. Eventually, quietly and possibly under assumed names, Whalley and Goffe left Judge’s Cave and slipped out into the bustling activity of the colonies, never to be heard from again.”

This and several other Sperry family stories are also recounted in an extraordinary genealogical resource, ‘That Great Sperry Family’ — an important record of the Sperry family, which traces its roots in England, as well as providing details about Richard's arrival in New Haven. Published in 1977, the book includes information on the descendants of the original Sperry family in North America, starting with Richard and Dennis Sperry, and tracing their descendants over as many as twelve generations on some branches as the family spreads out across the United States and other parts of the world. The book's author, Harrison Spencer Sperry, was a 6th great-grandson of Richard and Dennis (and a 6th cousin, 3 times removed, of the author of ‘TownHistory’). His dedication and enthusiasm for telling the Sperry family story is evident in page after page of his typewritten manuscript.

With some help from Harrison Sperry's book, tracing present-day members of the extended Sperry family to their roots in Woodbridge is often just a matter of working backwards until the right branch is located. So when an inquiry about Eastside Cemetery came by way of a recent phone call, yours truly was able to connect some dots. The caller was Sue Sperry who was planning a visit to Connecticut with her husband Robert ‘Buzz’ Sperry. Their branch of the Sperry clan had departed Connecticut to settle in Illinois at a time when many native New Englanders were on the move, heading west.

It was a delight to meet them at the cemetery and help them locate the gravestone of Buzz's 5th great-grandmother, Abigail Perkins Sperry (1723-1756), who is buried in the same row as my Sperry ancestors, Ensign Nathaniel Sperry, Jr. (1695-1751) and his son Sargent Simeon Sperry (1739-1805). Abigail was a daughter of Nathan Perkins (d. 1748) and his wife Abigail Hill (abt. 1693-aft.1775). She was married in 1746 to David Sperry (1722-1804), a son of Nathaniel's first cousin, John Sperry (1684-abt. 1754) and his wife Priscilla Hotchkiss (b. 1688). Although there is no gravestone to mark David's final resting place today it is likely he is buried at Eastside as well. In fact, at present there are 111 people with the surname or maiden name Sperry buried at Eastside according to the listings on the Find-a-Grave website.

Visiting the grave of Abigail Perkins Sperry (1723-1756) at Eastside Cemetery on Pease Road in Woodbridge, on October 3rd 2024.

David and Abigail Sperry's grandson, Joel Sperry, Jr (b. 1782) and his wife Bethia Sperry (1784-1807) lived in Avon, Connecticut where they had a son Eli Sperry (1804-1860) who married Charlotte Dix (1803-1870). By about 1842, Eli and Charlotte had made the decision to pick up and move from Connecticut to Illinois with their six surviving children, who ranged in age from 17 to about 2 years old — including Buzz Sperry's ancestor James Monroe Sperry (1838-1904).

Their move seems to have followed a period of loss for the family after their daughter Eliza died at the age of 3 in 1835, and their son Walter passed away at age 5 in 1840. While we may not know what motivated Eli and Charlotte Sperry to leave their home in Connecticut for the promise of the frontier, there are some historical clues to help us understand what influenced the many New England families who also made the move west at this time.

Connecticut during the early 19th century had been experiencing recurring outbreaks of measles, influenza, smallpox, and other communicable diseases — part of a broader pattern that affected much of New England. Diseases like smallpox became epidemic, “due to the smaller population and towns being spread out across greater distances, with major outbreaks occurring cyclically over the years as herd immunity waxed and waned.” Highly contagious viral diseases like smallpox were feared for high mortality rates and long-term health effects. Once such disease was present, it spread rapidly due to the lack of widespread vaccination and limited medical knowledge about containment.

Also at this time, the idea of Manifest Destiny — the belief that Americans ‘were destined by God’ to expand westward and settle new lands — offered families of this time period not only a promise of economic opportunity in the west but also a chance to participate in building a new society. This came at a time when the religious fervor of the Great Awakening had also swept through New England in its second wave between the 1790s and 1830s.

Illinois, which was part of the western frontier in 1842, offered families the chance to start anew in a less densely populated and healthier living environment — and all of this may have been part of Eli and Charlotte Sperry’s decision to move their branch of the Sperry family west.

During our visit at Eastside, we stood beneath a beautiful old tree. The headstone of Eli Sperry’s great-grandmother Abigail had found a protective home at the tree’s base, while its branches reached high into a brilliant blue sky. Based on the family tree Sue shared, it seems Buzz and I are seventh cousins, once removed. That connection may be too distant for todays' genetic DNA test kits to detect, but with good genealogy record-keeping we can still draw together the far-flung descendants of some of the first European settlers in Woodbridge — and welcome them back for a visit to see the land their family members once walked, many years ago.