Eliza Lines weaves a tapestry of stories in ‘Bethany and Its Hills’

“I gathered a posie of other men’s flowers, and nothing mine own but the thread that binds them.”

— Michel de Montaigne

With this quote from the French philosopher Michel de Montaigne (1533-1592) in its introductory essay, a local historian sets off to tell the story of Bethany, Connecticut with a deep respect for personal and collective memory. The author weaves together a tapestry of individual stories, transforming isolated fragments into a cohesive narrative that carries meaning across generations. The metaphor of threads inspired by Montaigne's quote is an evocative way to think about history. It suggests both fragility and strength — a delicate yet enduring connection between the past and the present.

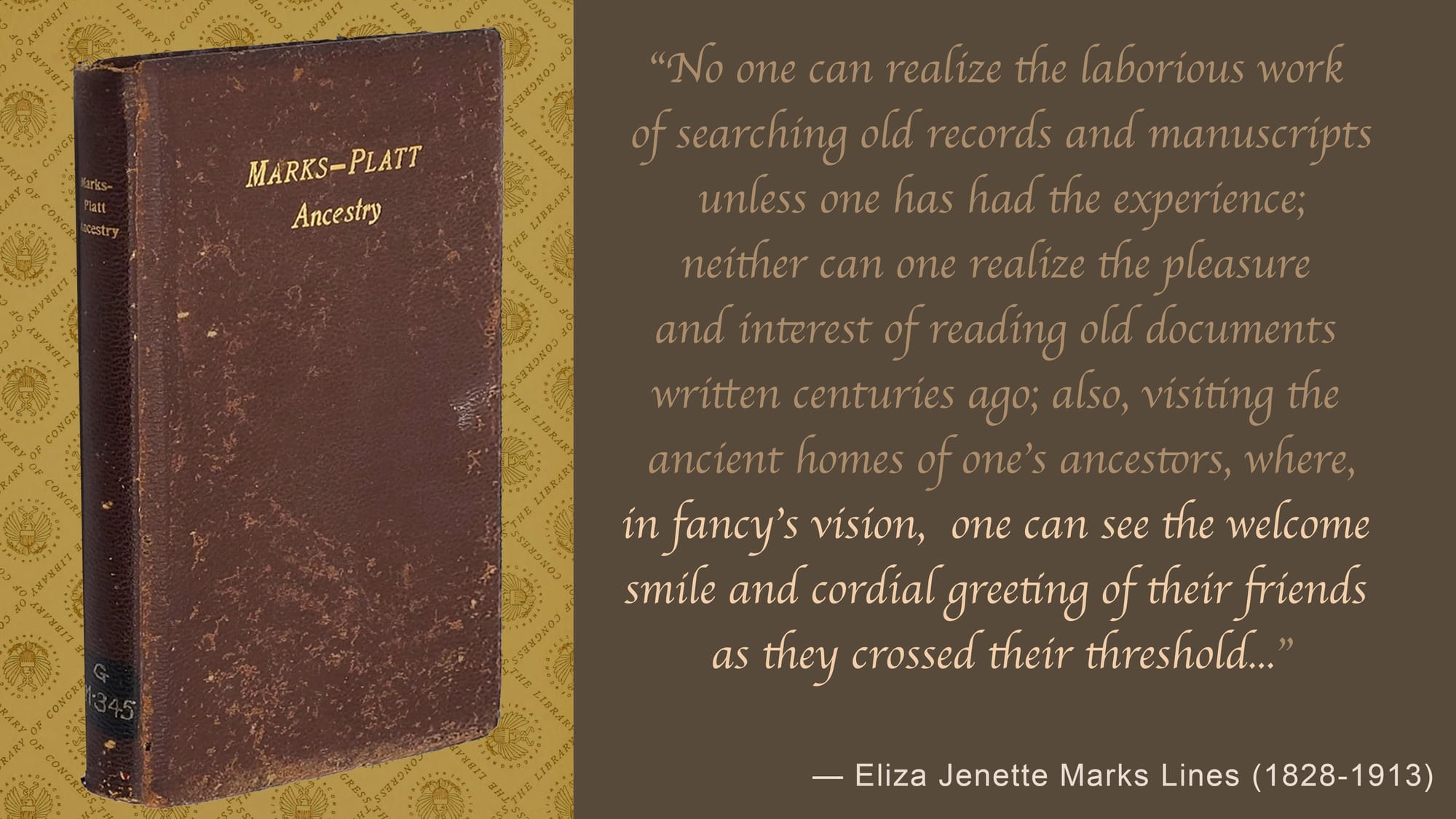

Eliza Janette Marks Lines (1828-1913), the author of Bethany and Its Hills, was a 19th-century historian and writer based in Connecticut. In her first published work in 1902, Marks Platt Ancestry, she traces her family lineage in detail. I was surprised by how many family branches we share — Eliza and I are connected by no fewer than 27 couples who are our common ancestors, going back to the early days of the colony (at our closest connection, through the family of Governor Robert Treat of Milford, we are 5th cousins, 5 times removed). Eliza's family tree also includes branches of the Merwin, Ives, Yale, Atwater, Doolittle, Blackman, Peck, and Cooper families.

Eliza was married at age 25 to George Henry Clinton (1821-1879), and when he died after 26 years of marriage, she wed Dr. Jairus Francis Lines (1834-1916), a son of Jairus Gilbert Lines and Sarah Prudentia Sperry. Eliza's second husband's paternal grandparents were Ransom Lines and Elizabeth Gilbert, and on his mother’s side, Abner Sperry and Elizabeth Gilbert (a third cousin of Ransom Line’s wife of the same name), making him a descendant of the Lines and Sperry families, as well as having a Gilbert connection on both sides of his family.

Through these familial connections, both Eliza and Jairus were intertwined with many of Connecticut's founding families with ancestors who played significant roles in the early settlement and development of the New Haven area. While Eliza did not have surviving children with either of her husbands (her son with George, George Henry Clinton, Jr. died at age 18 months in 1857 and another unnamed child also died in infancy the following year), perhaps the absence of direct descendants influenced her commitment to documenting the lives and stories of others, ensuring their memories were preserved and shared with future generations.

Without children to carry their lineage, Eliza and Jarius seem to have focused their energies on creating a broader legacy. Through Eliza's writings and Jarius's work as a Yale-educated doctor, they contributed to the collective history and well-being of their community. Their work symbolizes a different kind of generational impact — one that transcends bloodlines and instead ties them to the enduring fabric of local and cultural memory.

Eliza's use of threads as a metaphor in her writings becomes particularly meaningful in this light. While she and Jarius did not weave a direct familial thread into the future, their efforts bound them to the larger tapestry of history and humanity. This act of tying the past to the present — and leaving the stories for the future — reflects an expansive view of legacy, where an individual’s thread is connected to those who come after them.

After all the genealogical research she did for her 1902 book, in her second book published in 1905, Eliza took a different approach. As she explains in her introduction, while working to recount her Marks and Platt family ancestry, she was inspired by suggestions from friends and correspondence with those interested in genealogy and local landmarks, to undertake the project to document Bethany’s history, particularly as it existed before modern developments like railroads altered its character. She noted the importance of preserving memories of the town's early settlers and their homes, many of which had been lost to fire or decay.

Today, Eliza's book is available to read in its entirety, via the Internet Archive: Bethany and Its Hills.

Some of the themes of the book include the impact of industrialization and urbanization on small towns, the preservation of community identity and the remembrance of influential local families, and the role of religious and civic institutions in shaping Bethany’s development. Stories about significant cultural and social events highlight the communal nature of the town. For instance, the local fairs, church gatherings, and musical events are fondly recounted, showcasing a close-knit and vibrant community spirit.

In Bethany and Its Hills, Eliza sought to preserve the stories of Bethany for future generations. Drawing on her personal experiences, historical records, and extensive correspondence, she created a narrative that invites readers to connect with the past and reflect on its relevance today. In doing so she provides an extensive account of the town of Bethany, blending personal recollections, oral histories, and genealogical research.

Key events in Bethany's history are described including the robbery of Captain Ebenezer Dayton's house by Tories led by a British officer, with an account of the heroic resistance of Mrs. Phoebe Dayton. Further details on the capture and later escape of the robbers add a dramatic element to the narrative. This story also references the “the stolen boy” — Chauncey Judd — who was captured and nearly executed by the robbers but was ultimately saved by acts of bravery as members of the community intervened.

Eliza's text also dives into aspects of the architecture found in the town, including a detailed description of Captain Dayton's residence on Amity Road and further along the same road, the home known as the Wheeler-Beecher House, built for Darius Beecher. Eliza describes its grandeur, and unique features such as a smokehouse in the attic, as well as its historical lineage. The homes of other prominent families, like the Lounsbury and Perkins families, are also described, reflecting the architectural and cultural evolution of the town.

Family histories such as those of the Thomas, Hotchkiss, French, Perkins, and Tuttle families are chronicled, providing insights into their contributions to the community and genealogical connections. The remembrances Eliza includes also recount the manufacturing endeavors of Hezekiah Thomas and the tannery

business of Abner Perkins. The text concludes with genealogical details, emphasizing the interconnections of the town's founding families and their descendants. It also reflects on the enduring legacy of community resilience, cultural preservation, and the natural beauty of Bethany, symbolized by its landscapes and historic sites.

So we see that Eliza had a strong sense of connection to her ancestral and local heritage — including her connections to Woodbridge where she was born in 1828, the daughter of Levi Merwin Marks (1792-1880) and Esther Tolles Tuttle (1792-1858). Sadly, Eliza's grandmother Esther Tolles who also lived in Woodbridge, died giving birth to her namesake daughter on December 23, 1792 at just age 22. Her husband, Amasa Tuttle (1767-1827), would go on to marry Mary Beecher (1770-1829), a daughter of Captain David Beecher and Hannah Perkins (a previous post on Town History describes this Amity branch of the famous Beecher family). Eliza's connection to the Tuttle family included her grandfather Amasa's parents Uri Tuttle and Thankful Ives who lived on Carrington Road just north of Gaylord Mountain Road. In the 1972 publication Bethany's Old Houses and Community Buildings, by Alice Bice Bunton, the Uri Tuttle House is pictured and described:

This house was built by Uri Tuttle (died June 16, 1822, age 81), and the date is said to be 1765, which would make it one of the oldest houses in Bethany. Uri, son of Nathaniel Tuttle, was married in Bethany December 5, 1764, by the Reverend Stephen Hawley to Thankful Ives of Hamden (died August 1, 1834, aged 87). This union produced ten children. One of these, Calvin, owned the house in 1832. He married Sylvia Smith of Prospect, and they had six children. Calvin died March 12, 1844, aged 57, and Sylvia died November 6, 1870, aged 80. The last heir of Calvin and Sylvia, Elizabeth Harriet Tuttle, deeded the house March 27, 1900, to Clara S. Weed (died July 15, 1914), wife of Willard Weed, subject to life use, which she enjoyed for less than a year, dying March 2, 1901, aged 83.

The house is a story and a half with 12/12 sash in front down-stairs. There is space over the windows beneath the cornice. Small windows in the gable have 6/6 sash. The roof is later. Apparently the stairs were moved many years ago from the south room to the west room, which is now used as the front hall, one side of which has wainscoting of beaded featheredge boards. The former kitchen has wainscoting of similar boarding. Two paneled (quarter round type) rooms have a chair rail on three sides. The original doors are of featheredge boards. When the state highway was built, the house was moved to its present location.

The Uri Tuttle House on Carrington Road in Bethany over the years; pictured in Eliza Lines book in 1905, in Alice Bunton's book in 1965, and captured by Google Streetview in 2011 and 2023.

For Eliza, the threads of Bethany's history are personal, tied to the lives of families, the landscape, and the resilience of a community shaped by change. In transforming ephemeral moments into lasting memories by recording them, her work invites us to see how our lives are bound to those who preceded us and challenges us to consider what kind of threads we are weaving for the future.

Today, we extend these threads in new ways — through digital records, social media, and projects like TownHistory.org — creating modern layers in the fabric of history. By continuing to weave these threads thoughtfully, we can honor the past while ensuring that its lessons, beauty, and humanity remain vibrant for generations to come.

Reflecting on the idea of binding history to today, these threads become the ties that anchor us to our origins, ensuring that the lessons, values, and experiences of those who came before us are not lost. They remind us that the present is not created in isolation but is a continuation of a larger story — one that evolves but is always connected.