Remembering the one-room schoolhouses of Bethany and Woodbridge

This week, as news headlines announced the dissolution of the U.S. Department of Education, I found myself reflecting on what schooling once looked like in our community — long before there was any federal role at all. What did education feel like in small Connecticut towns like Bethany and Woodbridge in an era when lessons were taught in one-room schoolhouses, close to home, shaped entirely by local communities?

The answers live on in the stories and structures of these old community buildings, scattered across farm roads and hilltops. In those rooms, eight grades learned side by side under the guidance of a single teacher. Students walked from homes often miles apart, carried their lunches in pails, and huddled around wood stoves in winter. These schools were not just places where children learned to read and write — they were also the social and civic heart of our community.

Woodbridge’s educational history stretches back to 1740, when the town’s first school was established as part of Amity Parish. According to early records, this initial effort was partially funded by school money owed to Amity by the town of Milford. Soon after, two prominent residents — Ebenezer Peck (1684-1768) and Barnabas Baldwin (1665-1741) — petitioned New Haven’s First Society to secure Amity’s “proportionable share” of funds from the sale of common lands, which had been set aside to support schools. Local taxes were also levied to sustain the effort.

That first schoolhouse to serve the community (at a time when Woodbridge also included what is now the town of Bethany), was eventually known as the Southwest School. It was located between Old Racebrook Road and Racebrook Road. It stood as a symbol of the town’s early commitment to education, and over time, more schools were built to serve the scattered population.

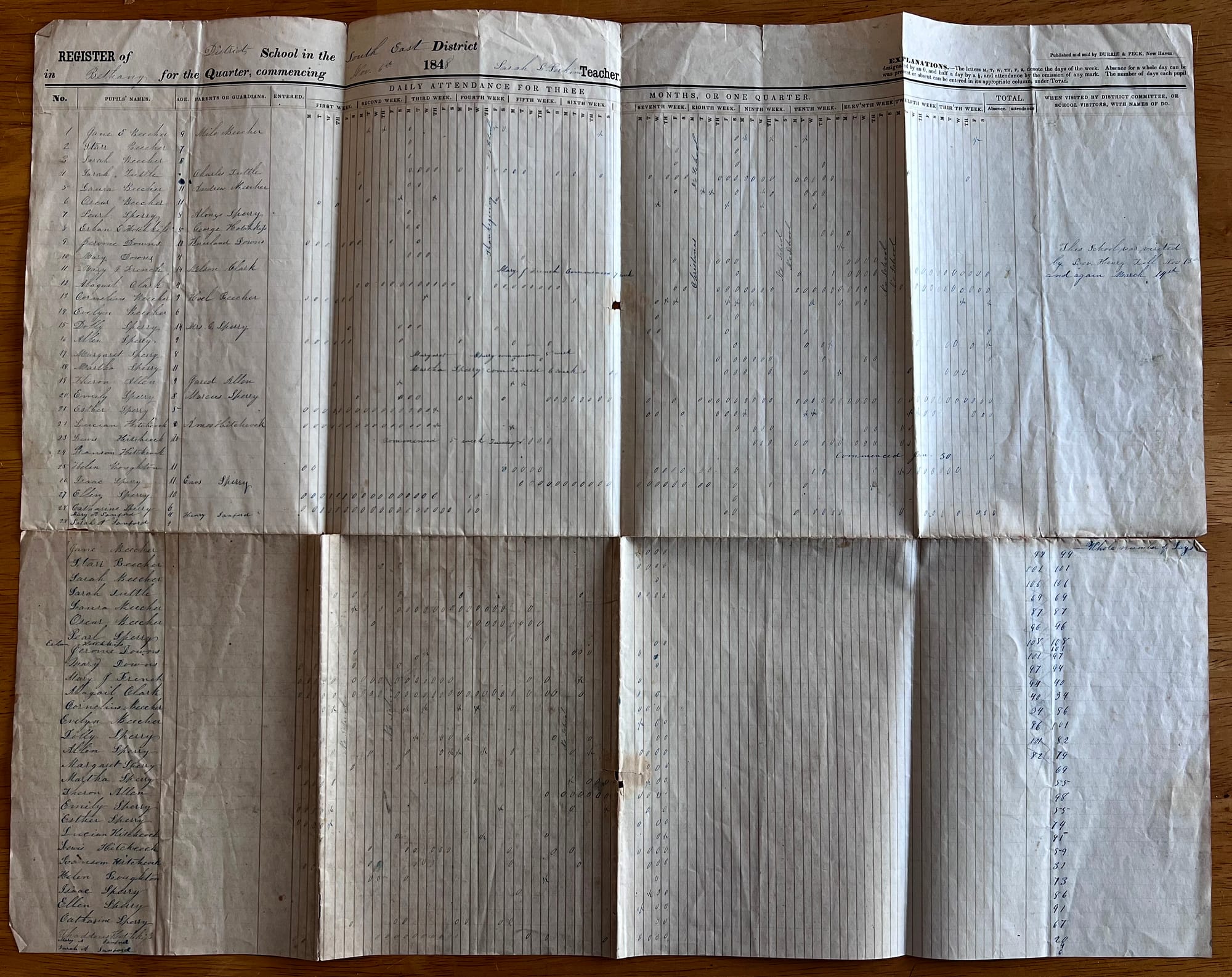

One of the more remarkable surviving documents from the one-room schoolhouse era is an attendance ledger from the South District School in Bethany, dated 1848. It includes the names, ages, and family connections of 28 students who attended that fall quarter. These names offer a glimpse into the families who lived in the area nearly two centuries ago, many of whom still have descendants in the region today.

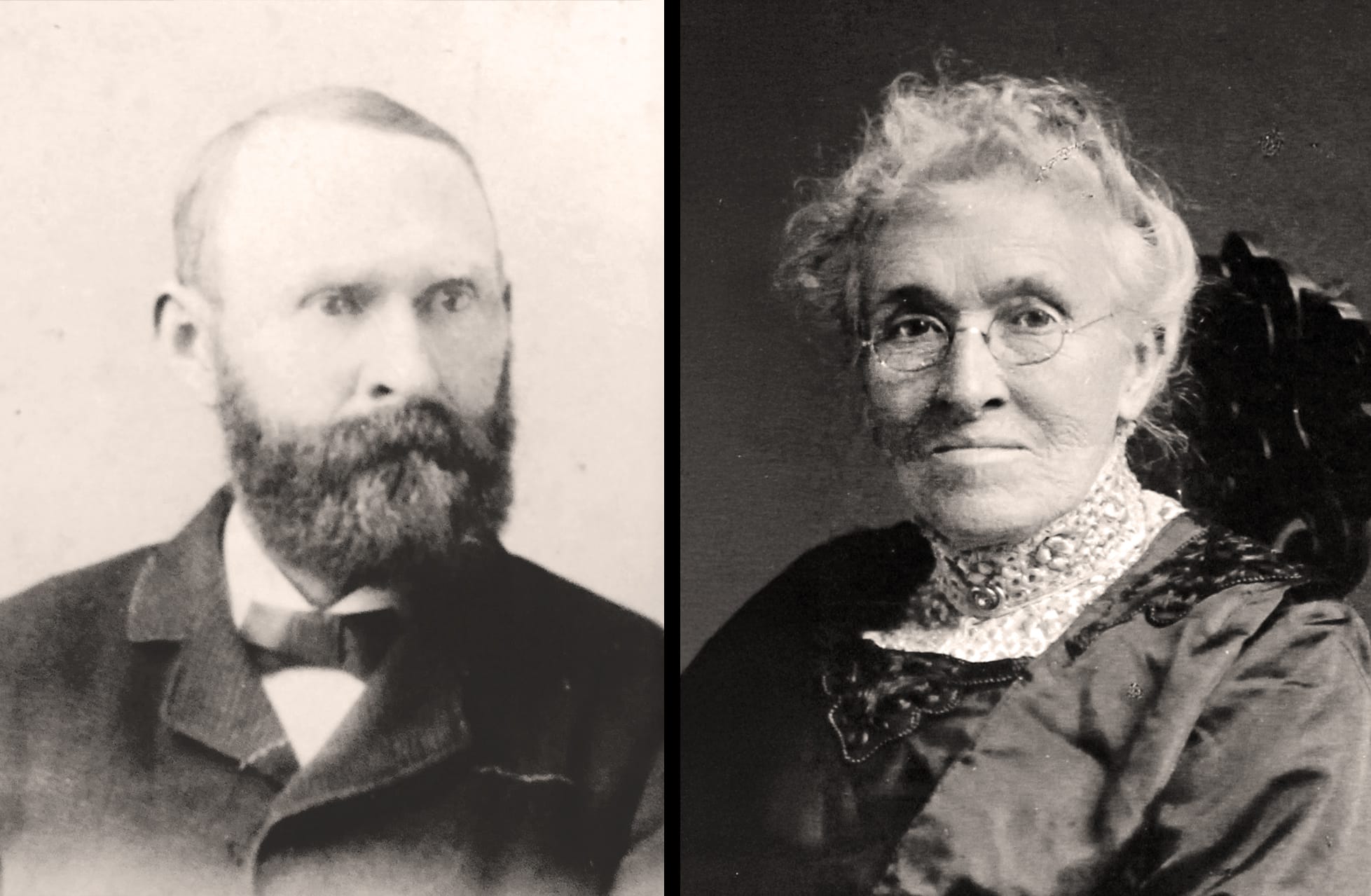

Among these is pupil no. 9, Jerome Downs, age 10, the son of Kneeland Downs (1809-1864) and Ann Andrew Downs (1804-1889). This is Jerome Andrew Downs, Sr. (1838-1904), whose Civil War experience was featured in a previous essay. Another notable student in this classroom, is pupil no. 28, Catherine (Kate) Sperry, age 6, a daughter of Enos Sperry (1801-1880) and Rosette Russell Sperry (1806-1893). Kate would later marry Henry Bishop (1846-1876) and later still become the great-grandmother of Kathryn Bishop Gartland (1935-2019).

Nearly 170 years later, I received this very attendance ledger from Kathryn while serving as editor of the 2016 second edition of Historic Woodbridge. We eventually discovered that my great-great-grandfather, Jerome Andrew Downs Sr., and her great-grandmother, Kate Sperry, were not only classmates — they were also fourth cousins, connected through multiple early Bethany family lines. That this fragile piece of paper survived long enough to find its way into the hands of two of these students' descendants is a reminder of how deeply intertwined our community is and serves as a testament to how local history continues to connect us across generations.

By 1896, Woodbridge had six one-room schools:

- The North School

- The Northeast School

- The Northwest School

- The Middle School

- The South School

- The Southwest School

Each of these schools typically had a single teacher instructing 12 to 15 students across eight grades. Because most children walked to school, these buildings were distributed across the town to keep the walk manageable for every family.

At the time, school administration was a hands-on affair — literally. The Superintendent of Schools would ride on horseback from one schoolhouse to the next, checking in on teachers, lessons, and building conditions. This image, quaint and rugged, underscores how rural and community-rooted the school system once was. By the late 1920s, Woodbridge began to transition away from the scattered, one-room schoolhouses that had served the town for nearly two centuries. The centralization of education came with the construction of a new grammar school—Center School—in 1929, marking the end of the one-room district schools.

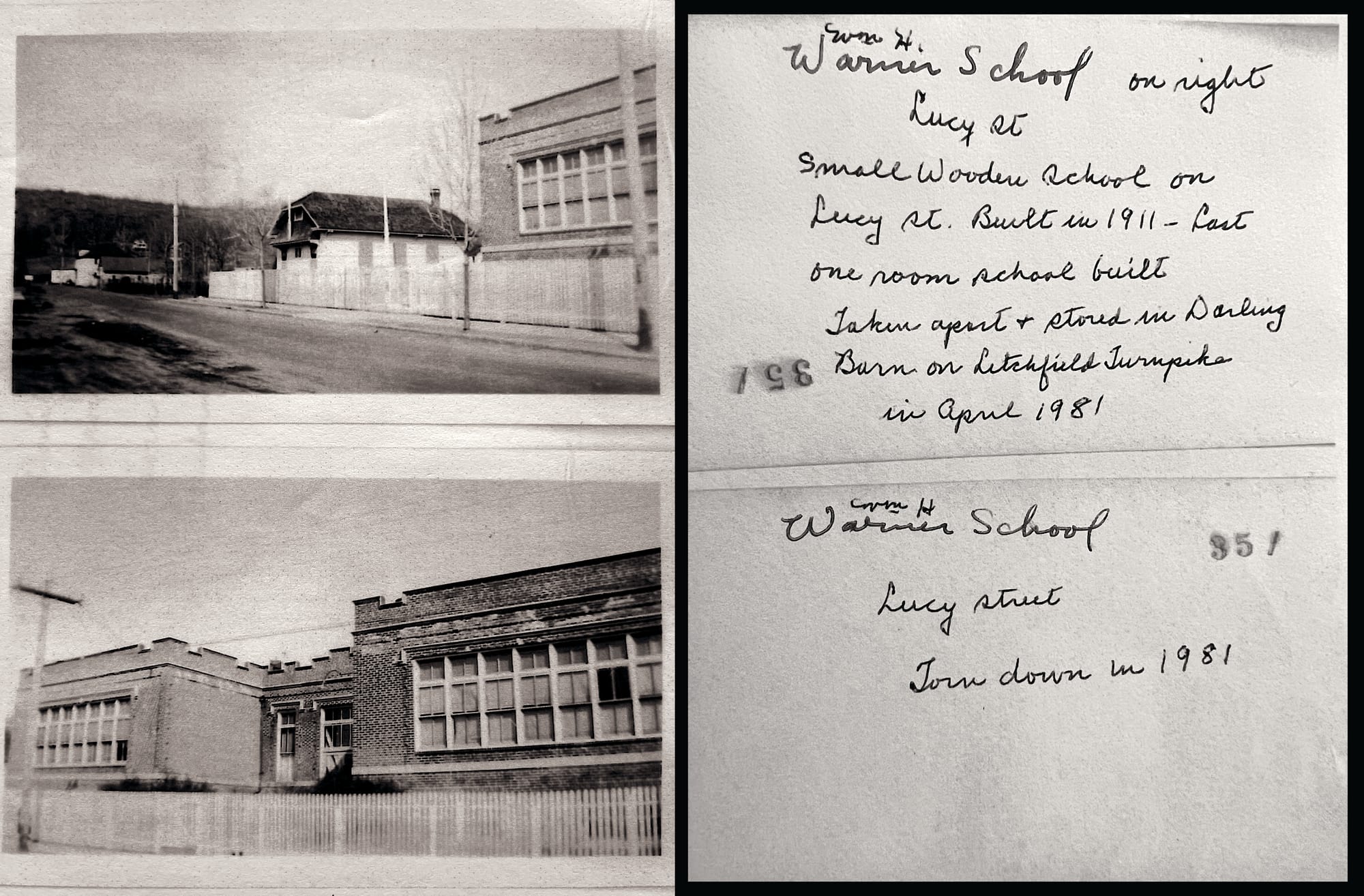

“Education was centralized when the new grammar school was built in 1929. Like many schools of the period, Center School was a brick Georgian Revival… When it was completed, all the one-room district schools were closed and only one other school remained open, Warner School on Lucy Street in the Flats.”

— Historic Woodbridge (2016)

The Warner School on Lucy Street, and the smaller structure that stood next to it called “Little Lucy” continued to serve students in the Flats neighborhood until its closure in 1956, when Center School was expanded to accommodate the growing population. See previous essay on William Warner, the school's namesake.

As the postwar baby boom swelled school enrollments, more schools were needed. In 1954, a regional high school was opened to serve Woodbridge, Bethany, and Orange — an important development for a town whose teenagers had previously attended high school in New Haven since 1905. The next major change came in 1960, when Beecher Road School opened and over time once Center School closed, became the town’s only public elementary school — a role it continues to play today (see previous essay on Beecher Road School renovation).

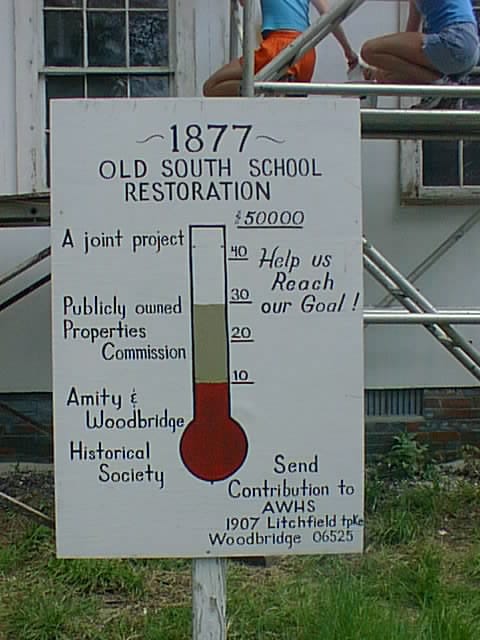

Meanwhile, the former district school buildings began new lives. One example is the Southeast District School, located at 1181 Johnson Road. Built in 1877 to replace an earlier 1866 structure, the small gable-roofed schoolhouse remained in operation until 1929. From that point through 1938, it served as a firehouse and was later used as a community meeting hall. Though modest in size (30’ x 24’), the school retained many of its original features, including 6-over-6 sash windows and one of its twin entrances. A Victorian-style porch and cupola that had been removed during the firehouse years were faithfully restored in a renovation project undertaken as the town approached the turn of the millennium.

The South School Restoration Committee was supported by the Amity & Woodbridge Historical Society as it embarked on this years-long effort to restore the building to its original appearance. Community members pitched in with donations and helping hands, including students from Amity High School’s Girls Cross Country Team, who volunteered to spend a Saturday in 1999 scraping, sanding, and preparing the building.

Restoration of the Old South School, Woodbridge The one-room schoolhouse at 1181 Johnson Road being restored in 1999 as volunteers including local students contributed helping hands to bring it back to life.

In 2002, the school received a new wood shingle roof. By 2003, interior work was underway. That summer, volunteers rebuilt the original front porch, removed in 1928, using historic photos and the “shadowline” still visible on the building’s clapboards as a guide. The school’s original bell — removed during its conversion to a firehouse in the 1920s — was rediscovered in the collection of the Amity & Woodbridge Historical Society, labeled as the “South School Bell.” It had been preserved by George Knowlton, fire chief at the time. The bell was installed in the new cupola and proudly rung again during the rededication ceremony in June 2013.

Today, the South School stands as the best-preserved of the old Woodbridge district schools. Others have been converted into private homes, their schoolhouse pasts visible only in rooflines or window shapes.

Meanwhile, up the road in Bethany, five one-room school houses served the community. According to Alice Bice Bunton's book Bethany's Old Houses and Community Buildings, these were:

The Center School, Bethany’s oldest schoolhouse, was built in 1834 and originally stood on Peck Road, opposite today’s firehouse on Amity Road. It served the Union or Center District, which was a combination of the South, West, and Middle Districts. Hezekiah Thomas, one of the first teachers, also ran a nearby hotel. Over time, the simple one-story building was enhanced with a bell cupola and a front porch. The school operated until 1933–1934, with Eleanor Kazanjian as its final teacher. After closing, the building was repurposed as Bethany’s first volunteer firehouse. In 1951, when a new firehouse was built, the schoolhouse was sold to the Bethany Athletic Association, which moved it to Munson Road and converted it into a clubhouse.

The Beecher School, located on Sperry Road about a mile south of Hatfield Hill Road, served the southeast or Beecher District. It is the third schoolhouse to occupy this site; the district was established in 1789, and this current building was constructed in 1870, replacing earlier structures from 1789 and 1812. In 1899, it was enlarged to include a porch and a bell tower. The building remained in use as a school until 1934, after which the town voted to sell it. Asa Curtiss purchased the building in 1947 and moved it across the road, remodeling it into a residence.

The Gate School stood on the east side of Litchfield Turnpike, just south of the Cheshire Road intersection, near the site of the old Archibald Perkins toll gate. The district, once known as the North District and later the Gate District, was first established in 1781. A schoolhouse was built there early in the 19th century, but by the late 1800s it had fallen into disrepair. In 1880, it was replaced by a new building slightly to the south, which served as a school until 1934. The final structure was remodeled in 1938 by Harold Anderson as a residence. The school is remembered in early town records, which noted votes on repairs, equipment, and teacher wages — at one time, just a dollar a week.

One of the school’s most beloved teachers was Miss Albena Pilvelis (1907-1980) who would later marry Wesley D. Doolittle (1900-1983), whose family owned the adjacent property. As a young school teacher she arrived each day by horse and buggy, often parking at the bottom of the hill in snowy weather and walking the rest of the way on foot. In her time, the school had no running water or plumbing and was heated by a single wood stove, but she faced each day with steady resolve. More memories and a photograph of Mrs. Doolittle can be found at BethanyHistory.com.

The Downs Street School, located just south of the junction with Hatfield Hill Road, was built in 1897–1898 to replace a much older building that had been in use since before 1800. Julius and Mary J. Doolittle sold the property to the school district in 1896, and the school was constructed under the direction of Andrew J. Doolittle, who was praised for the quality of his work. The building remained in use until 1925. That same year, Henry G. Doolittle purchased the property back from the town, and it was passed down through his family. By 1962, the building had been converted into a private home.

The Smith School served the Northeast or Smith District of Bethany and stood on Carrington Road, about a quarter mile north of Davidson’s Corner. The first schoolhouse on this site was a simple structure under a large chestnut tree near J. B. Todd’s house. The second schoolhouse, in use from 1832 to 1876, was replaced in 1877 by a third structure built by Denzil B. Hoadley. This third school continued in use until it was discontinued in 1923. The building was then sold to Edward Wooding and passed through several hands before being acquired by Charles E. and Rose A. Fox in 1965. One of the early teachers, Julia Bradley, later became Mrs. Leonard Todd.

In her 1997 book Bethany Pebbles & Flowers – Memories of Life in a Rural Connecticut Town, Hazel Lounsbury Hoppe (my grandmother Dorothy's sister) captured the deep sense of place and memory rooted in Bethany's one-room schools. The Beecher School, where the five Lounsbury girls attended, she recalled, “provided one of the primary focal points in our lives.” Alongside the other one-room schools of this era, it formed part of a small but interconnected educational system that shaped generations.

“Three one-room schools served to educate the town’s children in those years… we proved to be as well educated or better than some of our high school peers. Discipline was firm in those days, and we were inspired by dedicated teachers to perform to the best of our abilities.”

Hazel also described how, each spring, students from all three schools would gather at the town hall for spelling bees, speaking contests, and Field Day. These friendly competitions “were an important part of our education,” offering rural children a rare opportunity to socialize and demonstrate their accomplishments to the wider community.

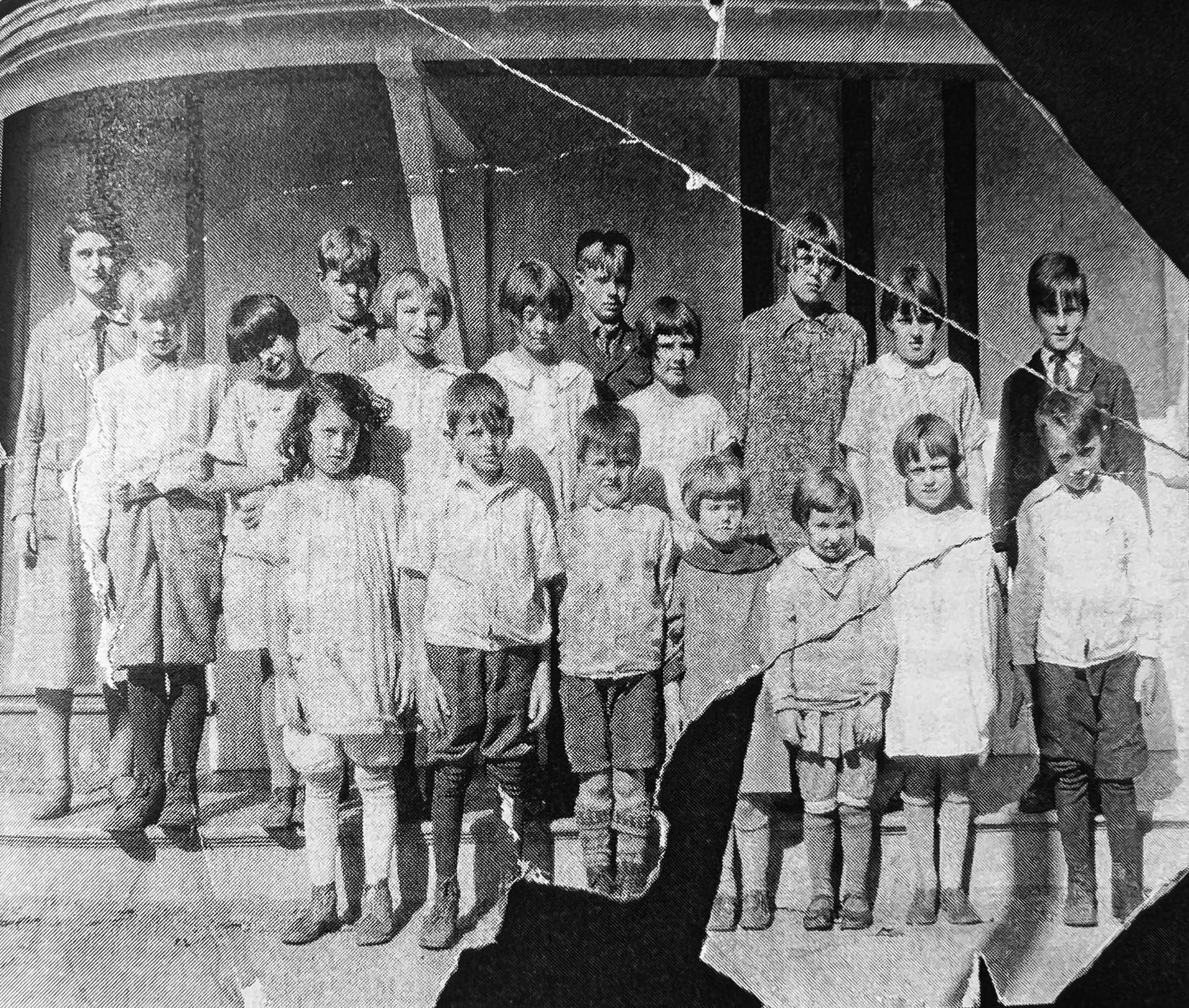

While the one-room schoolhouse era is often remembered fondly, the reality for students and teachers was often challenging and sometimes tragic. Epidemics of contagious diseases such as diphtheria, scarlet fever, typhoid, and influenza regularly disrupted school life. In Bethany, both the Center School and Beecher School were at times closed due to outbreaks, requiring deep cleanings before children could return. During the 1918 influenza pandemic — known as the Spanish Flu — a particularly poignant story unfolded at the Smith School.

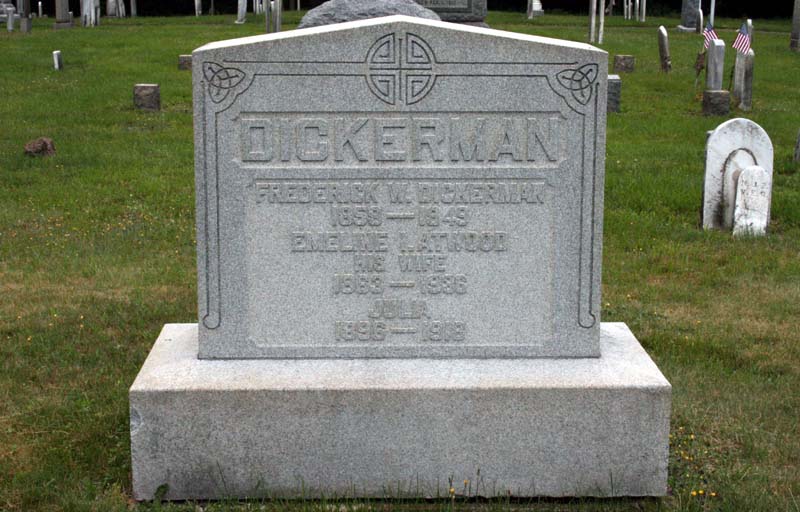

In her 1978 book Bethany Yesterday: The One Room Schools, Hazel described the fate of young schoolteacher Julia Edith Dickerman in vivid and personal terms:

“Memory has a way of painting the days of our youth with a rosy glow, but those long ago days were far from idyllic. Among the many problems that plagued our town were the illnesses common to those early times. There are records of serious illnesses such as diphtheria, scarlet fever, and even typhoid. At different times, both the Center School and the Beecher School were closed for a few weeks due to a scarlet fever epidemic. Then the schoolhouse would be cleaned and fumigated before the rest of the children would be allowed to return. The influenza epidemic during the first World War is remembered sadly by several of the students who attended Smith School at that time, for a tragedy developed when their well-loved teacher, Miss Julia Dickerman, was taken seriously ill during the school day.

Miss Dickerman was a very young teacher, for only two years before she had been an apprentice teacher, at the Center School, under the direction of Miss Twing. Every morning she drove her horse and little buggy over the hills to Smith School from her residence in Mt. Carmel.

On one particular morning, early in the autumn, of 1918, she told the children that she felt very ill, and she asked one of them to bring in the horse blankets from her carriage outside. Then she spread the blankets on the floor of the platform beside her desk and lay down and then, seemingly shaking with a chill, she covered herself with her coat. She told the children to go out to recess. If the youngsters had been aware that she was seriously ill, they may have had the common sense to go down to Tyler Davidson’s house for help. Instead, they went in the other direction, northward to the Coe Orchards. Along the road, fortunately, came Mr. Ireland, the superintendent, in his little car. Seeing the children in the orchard, he stopped and questioned them. The youngsters quickly ran back to school, for, still not realizing how desperately ill Miss Dickerman was, they thought that she might be in trouble for lying down when she was supposed to be teaching school.

Instead, they were surprised to find the supervisor putting the teacher into his car; he then dismissed the pupils for the rest of the day. Several days later the sad news came back; their dearly loved Miss Dickerman had died with the influenza.”

With no substitute teachers available and wartime rules prohibiting the employment of married women in teaching roles, the Smith School remained closed for several weeks. Eventually, the town made an exception and invited Mrs. Jerome Downs — Josephine Nettleton Downs — to complete the school year. A seasoned educator, she had previously taught at the Downs Street School and was well respected in the community. Her husband, Jerome A. Downs Jr. (1869-1938), had served as First Selectman of Bethany from 1903 to 1908 — and was also the grandfather of the author Hazel Hoppe who would go on to preserve so many of these local schoolhouse stories for future generations.

Today, only a few of the original schoolhouses remain — some lovingly preserved, others quietly repurposed. But the echoes of chalk on slate and the warmth of coal stoves still live in the memories passed down through families, in town records, and in the pages of books like those by by grand-aunt Hazel Hoppe. These stories remind us that education was never just about reading and writing — it was about preparing young people to take their place in a community that depended on them.

At a moment when the structure of public education is once again being debated at the national level, it feels all the more important to remember how deeply local and personal schooling once was — and how much it shaped the towns we still call home. The one-room schoolhouse reminds us that a classroom can be both a place of learning and a gathering place for the soul of a town. They serve as a lasting tribute to the people who filled them with purpose, day after day.