Sperry family members ‘Wide Awake’ as the civil war nears

A current exhibit at the Connecticut Museum of Culture and History on Elizabeth Street in Hartford offers a glimpse into the past — and in doing so, illuminates another chapter of Sperry Family history. The exhibition, Wide Awakes: Campaigning for Lincoln, runs through March 16, 2026 and is well worth a visit. It features artifacts that tell a story set “during a time of deep political division and fears of a civil war.” According to the museum website:

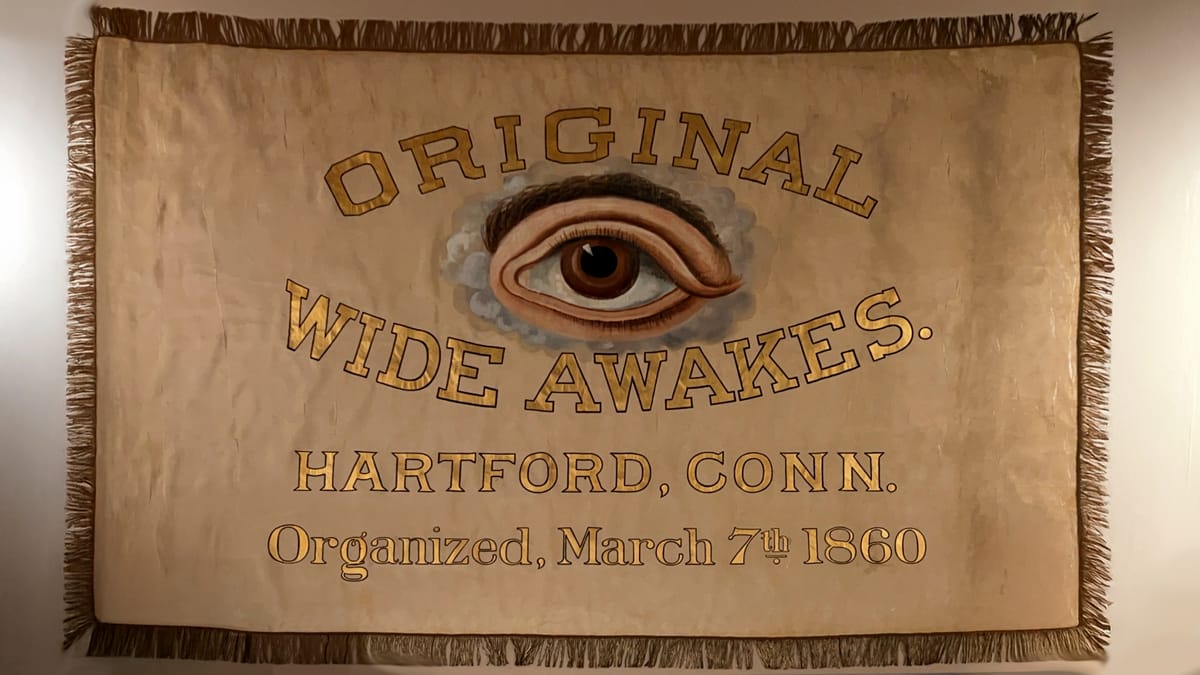

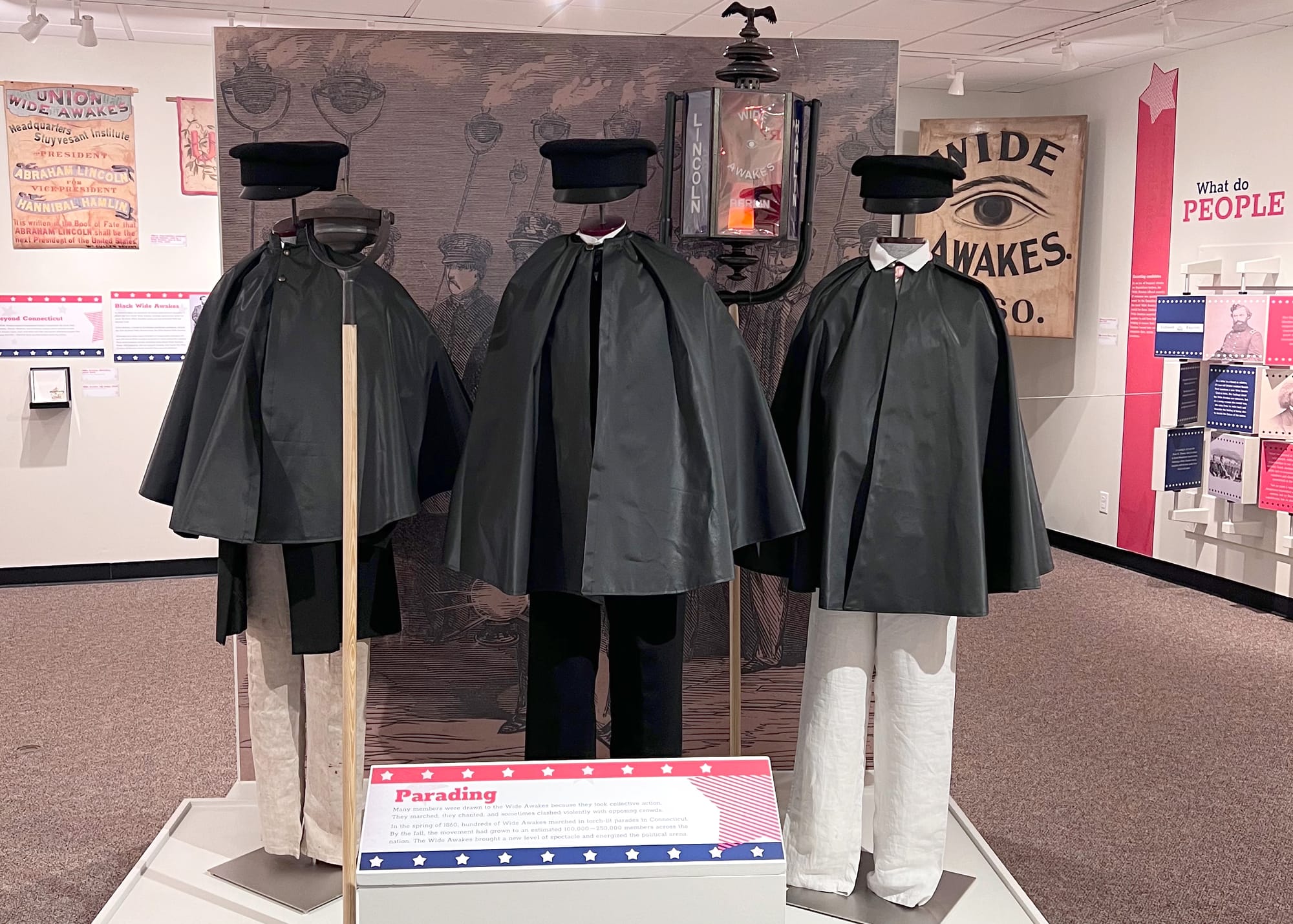

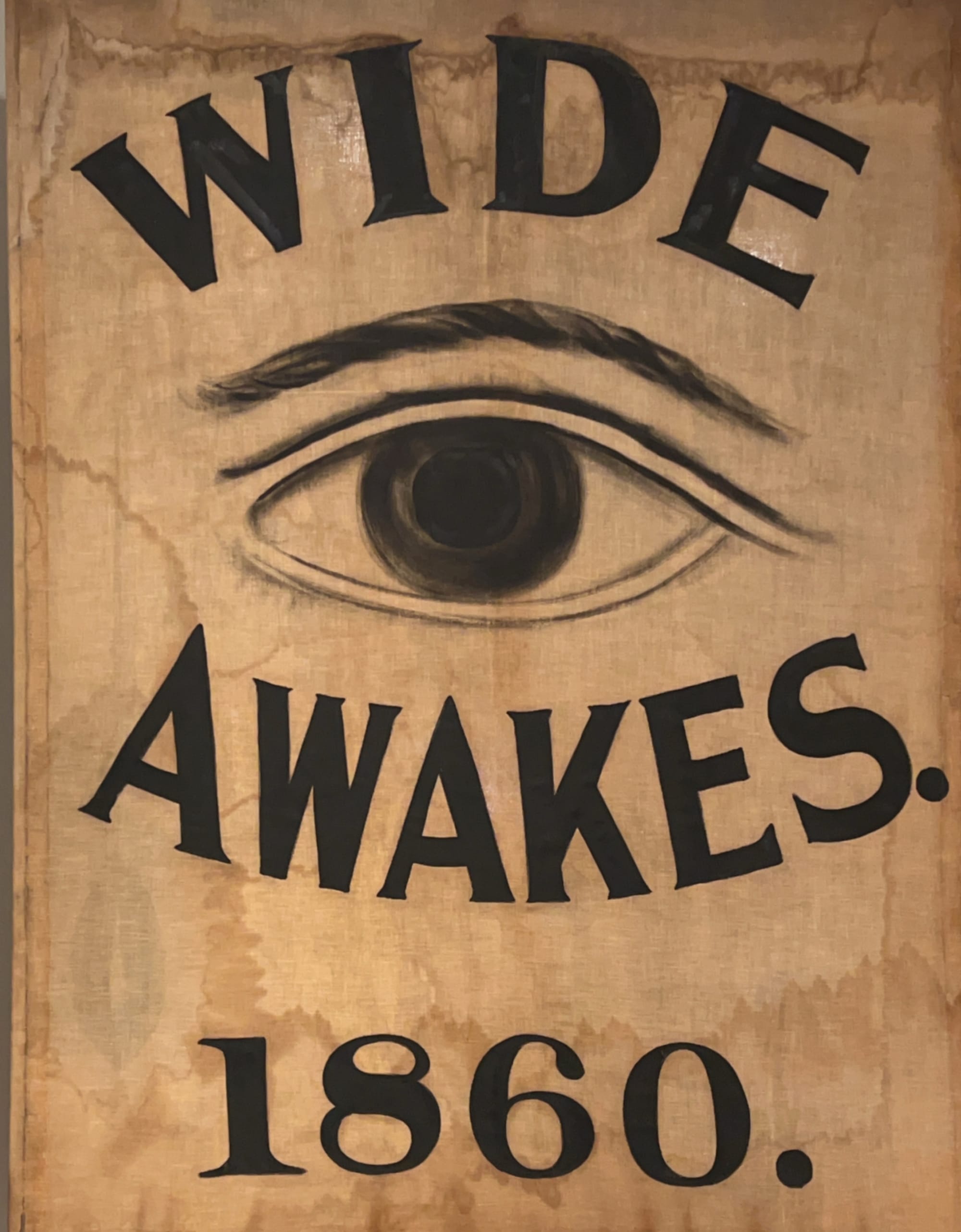

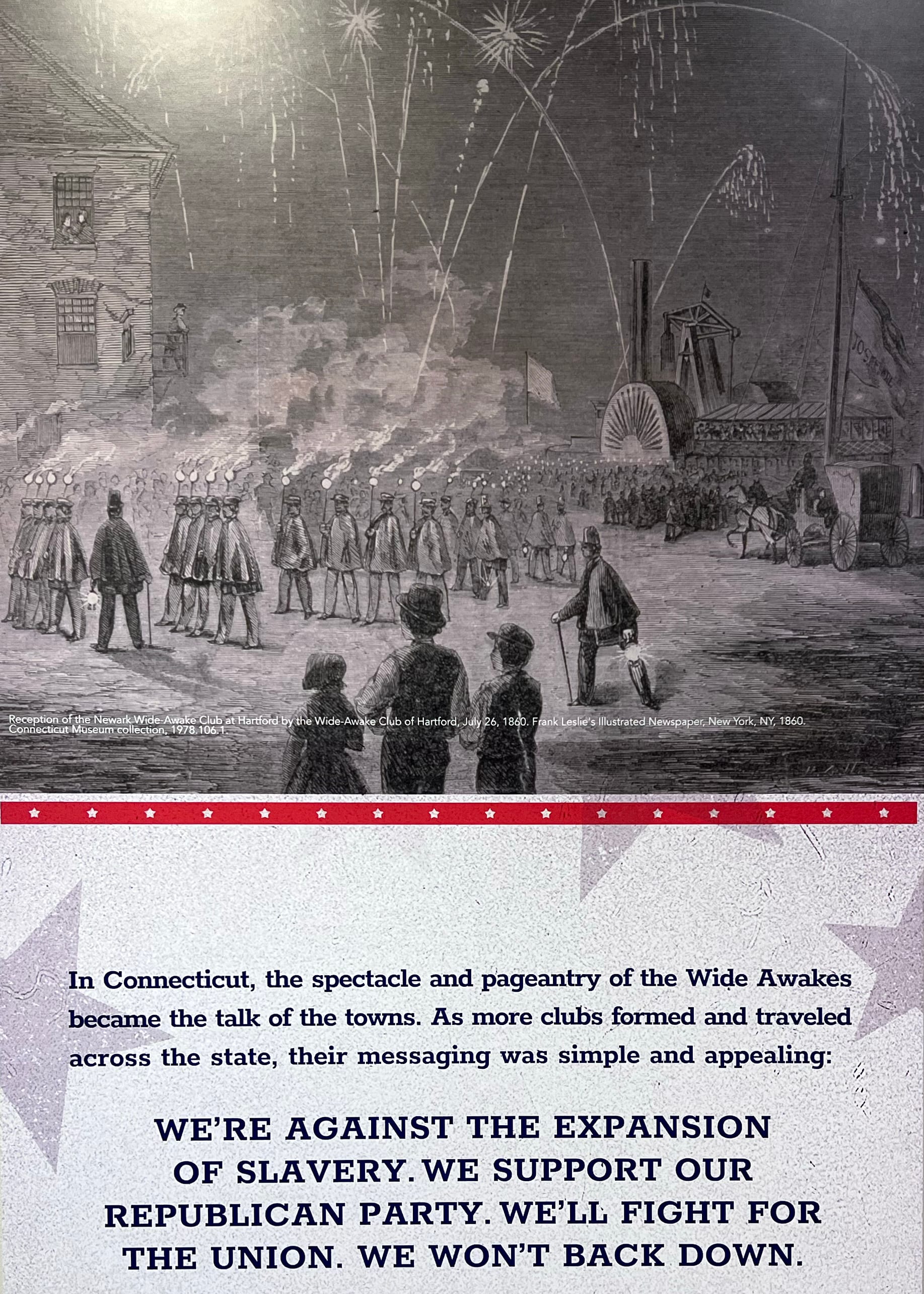

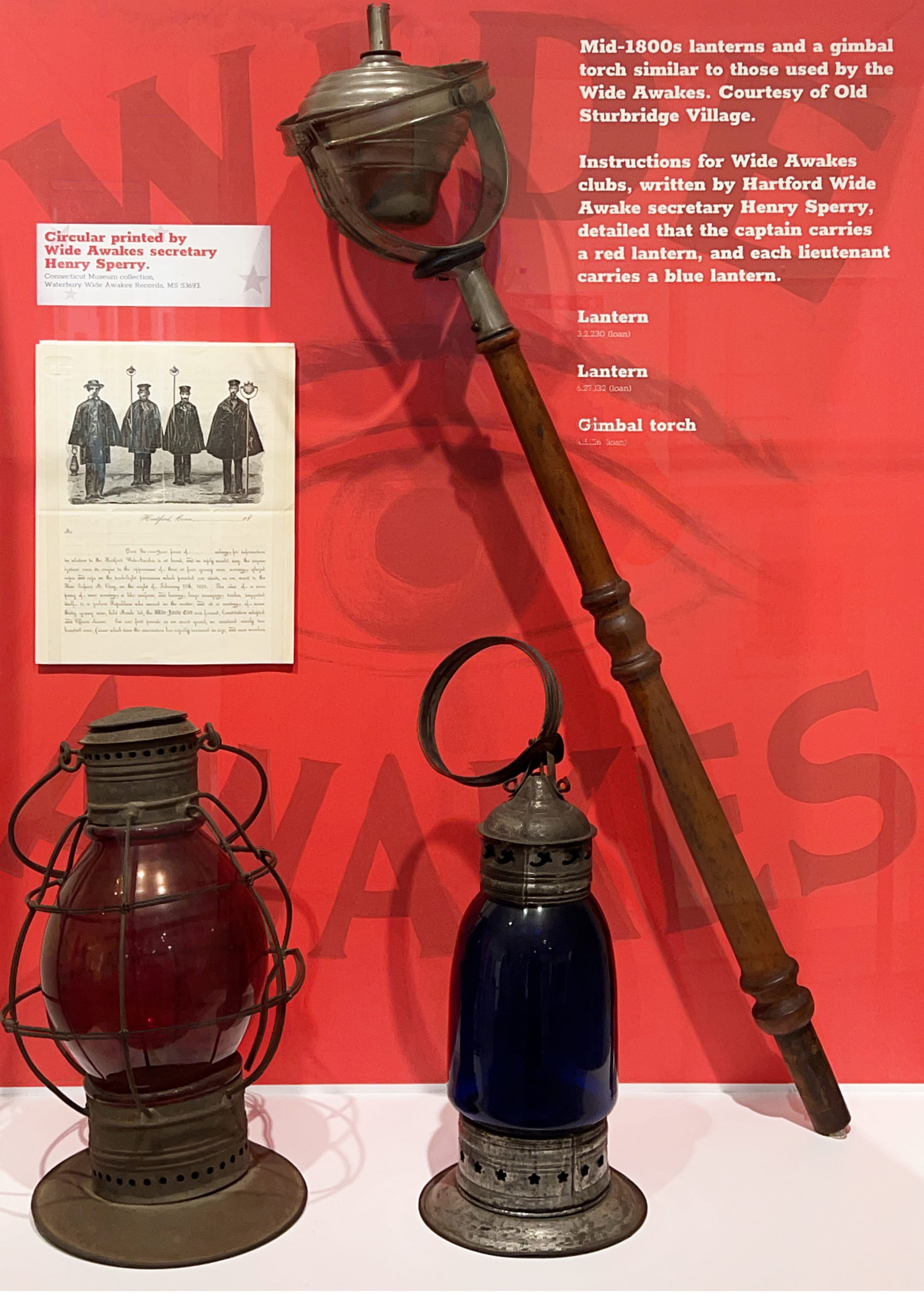

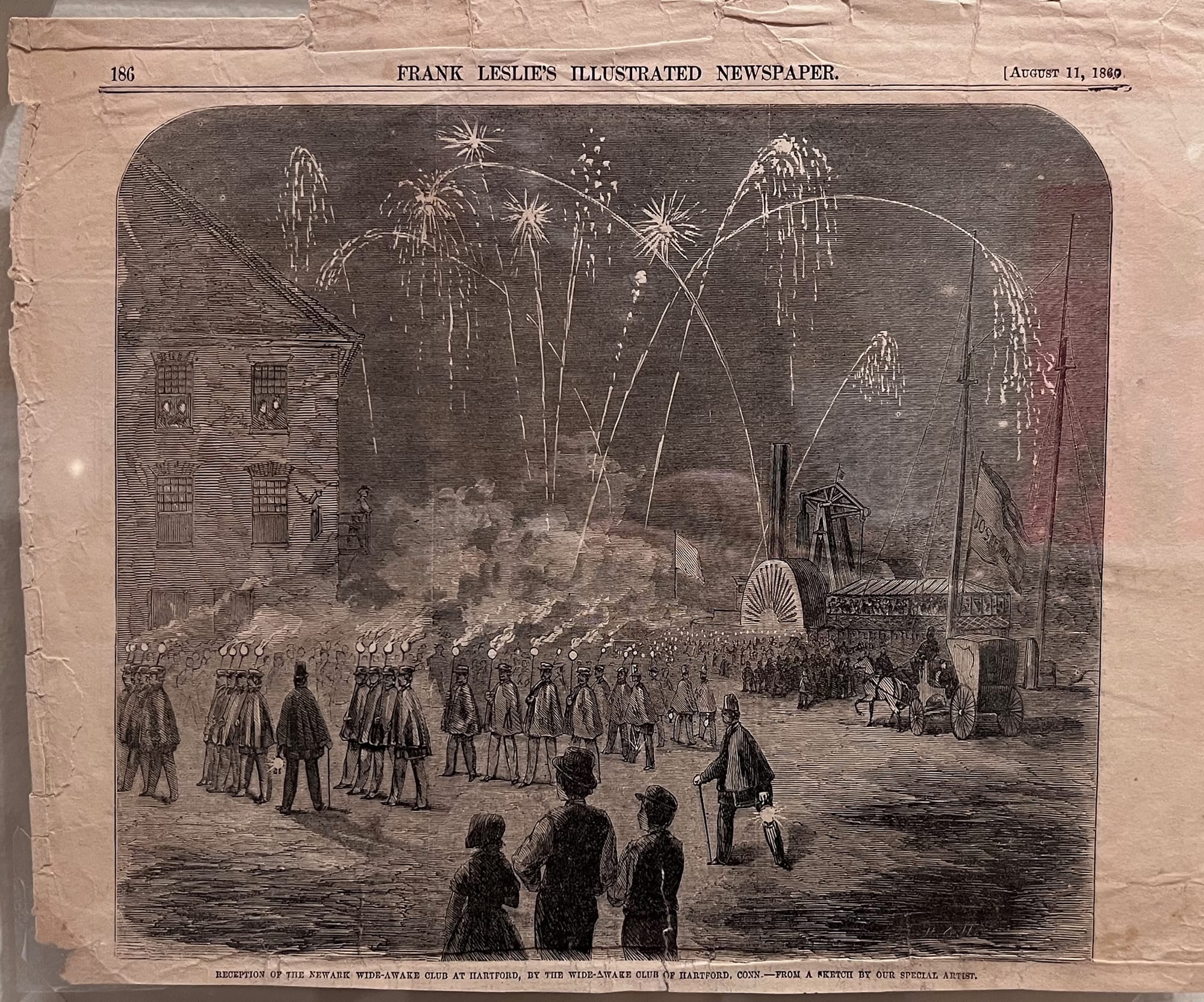

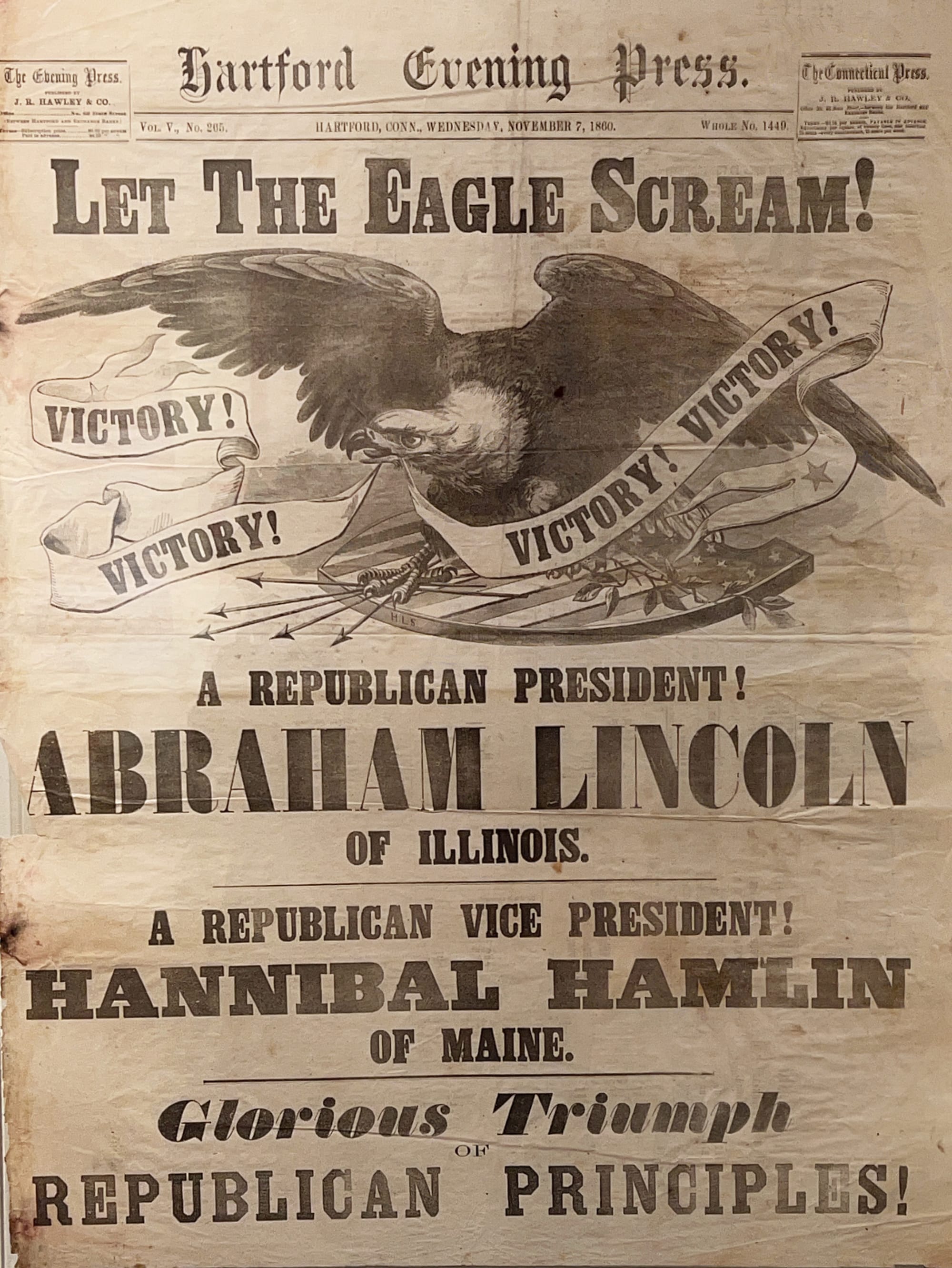

“This exhibition will transport you to the cusp of the election of 1860, when the political landscape was tense and the issue of slavery remained at the forefront. Discover the formation and rapid spread of the original Wide Awakes, a grassroots Republican campaign organization founded in Hartford, Connecticut, that rallied and paraded in support of Abraham Lincoln during the presidential election of 1860. They donned capes as uniforms, held torches and signs bearing an iconic eye symbol, and matched their bold image with bold actions.”

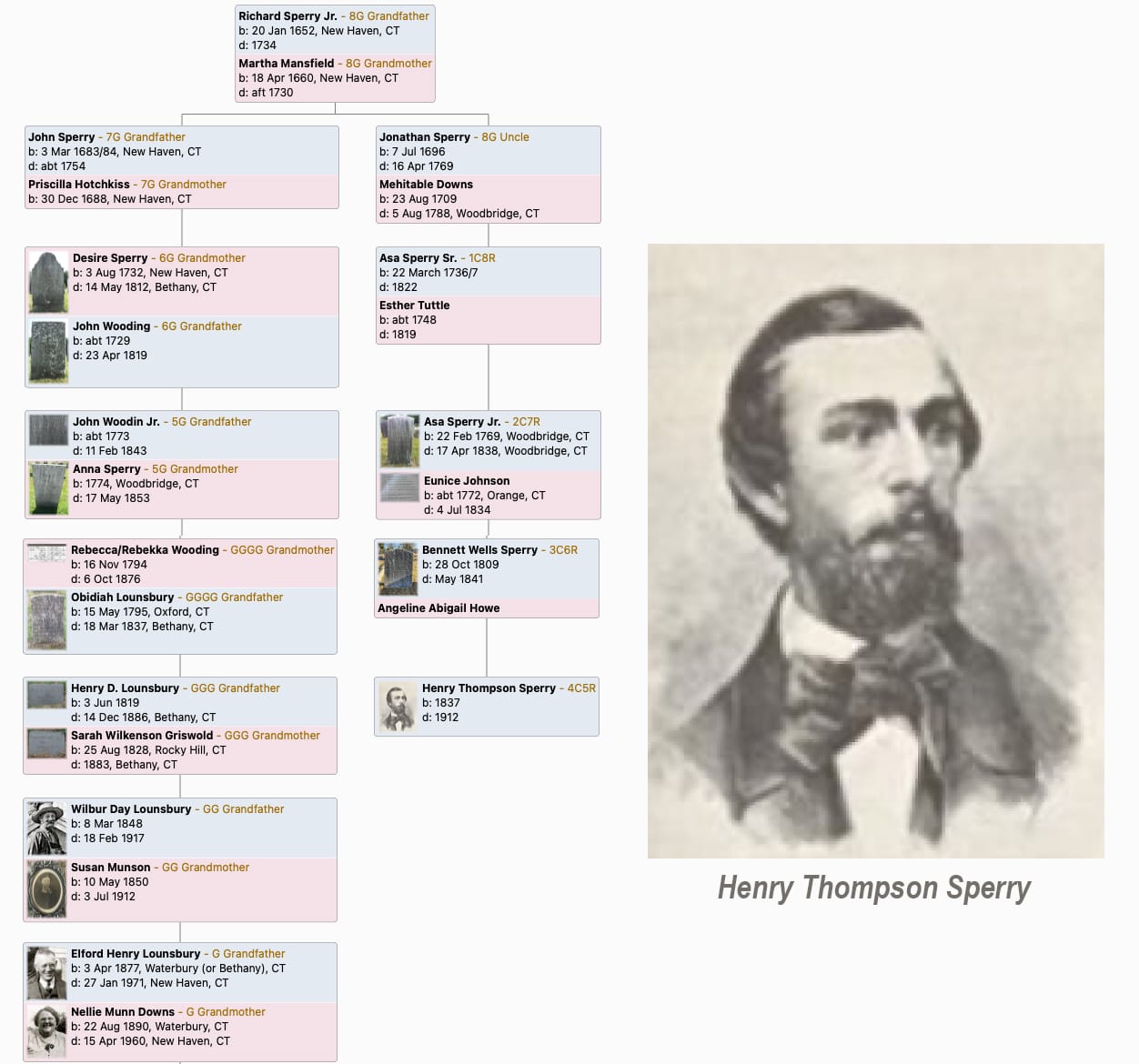

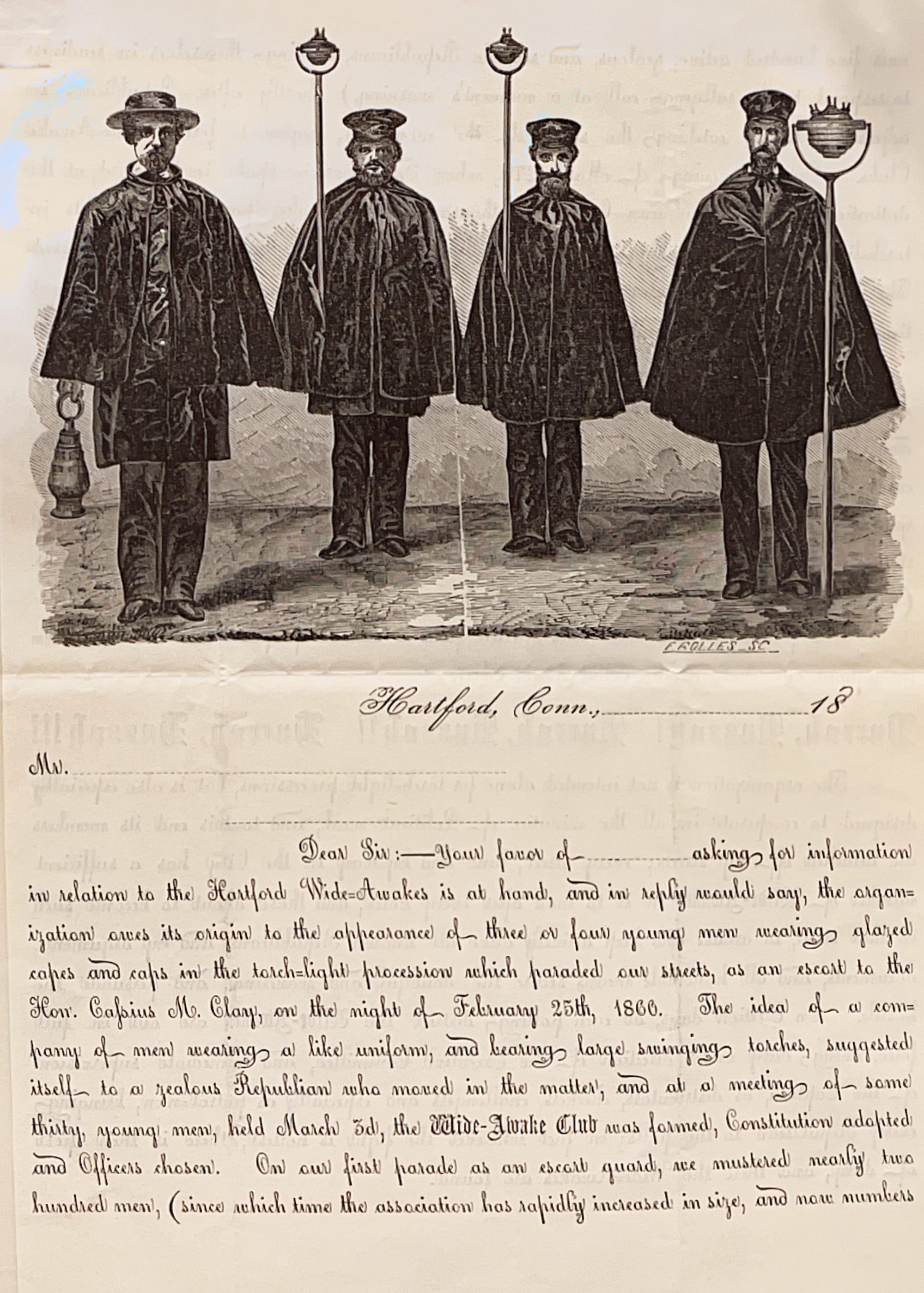

Visiting the museum this week, I was looking for information that might add context to the Sperry family connection I already knew about: one of my 4th cousins, five times removed, was Henry Thompson Sperry (1837-1912) who I had recently learned served as the Secretary of the Hartford Wide Awakes. Henry was a 4th great-grandson of Richard and Dennis Sperry, the couple who settled in what is now Woodbridge in the mid-1640s, though their son Richard Jr. and his wife Martha Mansfield (from whom my line also descends).

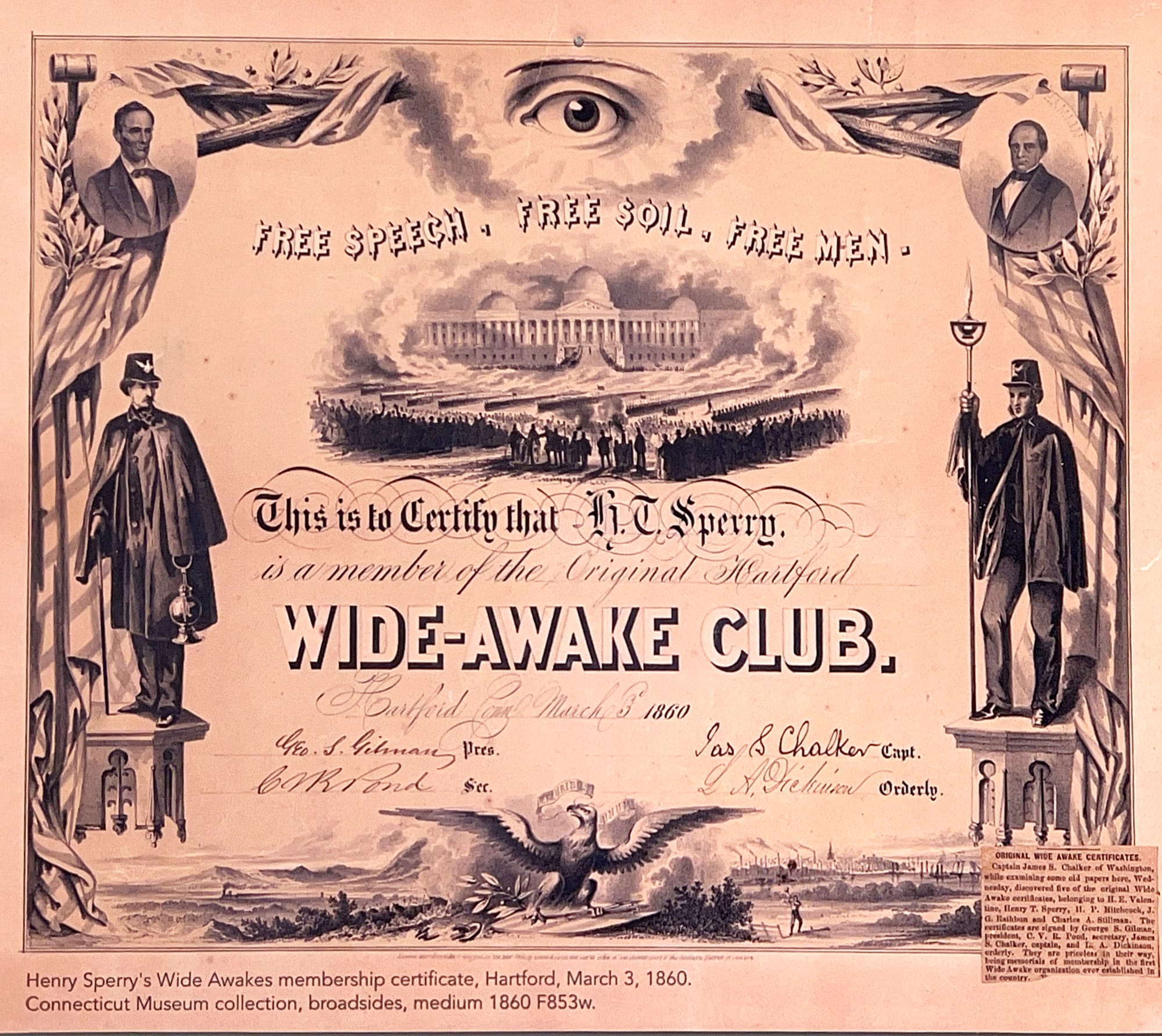

Although Henry was apparently not one of the five originating members of the Wide Awakes (the exhibit includes a dramatic telling of the moment these young men were ushered to the front of a procession leading the anti-slavery advocate Cassius Marcellus Clay to his hotel after a speech in February 1860), he seems to have joined the newly formed group very early in its existence. In fact, Henry's own original membership certificate, dated March 3, 1860 — four days before the organization date on the group's gold-gilded banner — is among the artifacts on display.

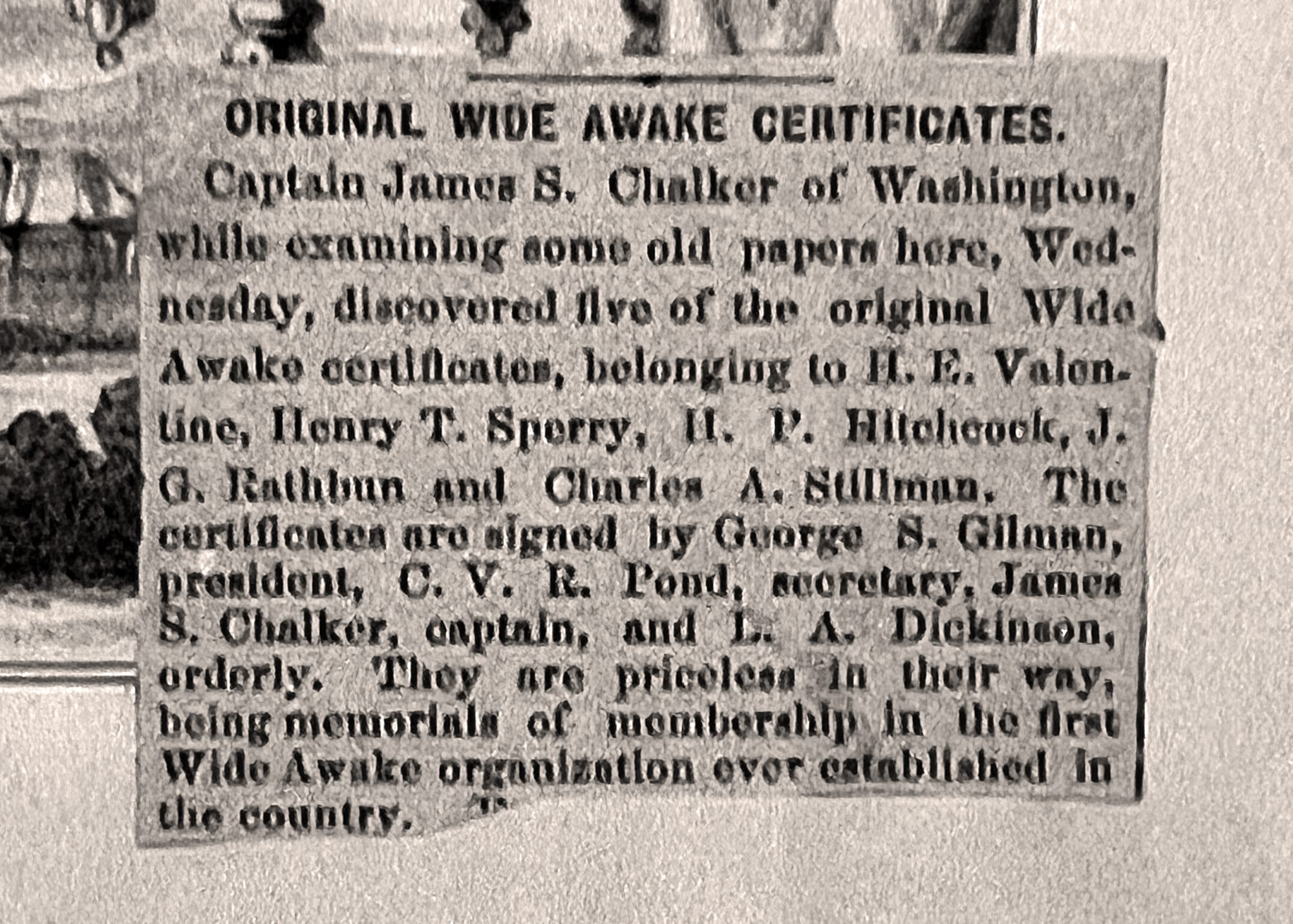

The news clipping that accompanies the certificate (bottom right corner of the display) describes the discovery of five of these certificates and states that they are “...priceless in their way, being memorials of membership in the first Wide Awake organization ever established in the country.”

Henry, just 23 years old at the time he joined the Wide Awakes, is also mentioned in the descriptions of some the other items in the exhibit and his pivotal role facilitating the spread of information about the Wide Awakes is detailed. He wrote hundreds of fliers, letters, and editorials to promote the movement, contributing to its rapid growth across the Northern states.

Items from the exhibit “Wide Awakes: Campaigning for Lincoln” include several that mention Henry T. Sperry (images 3, 4, and 5 above).

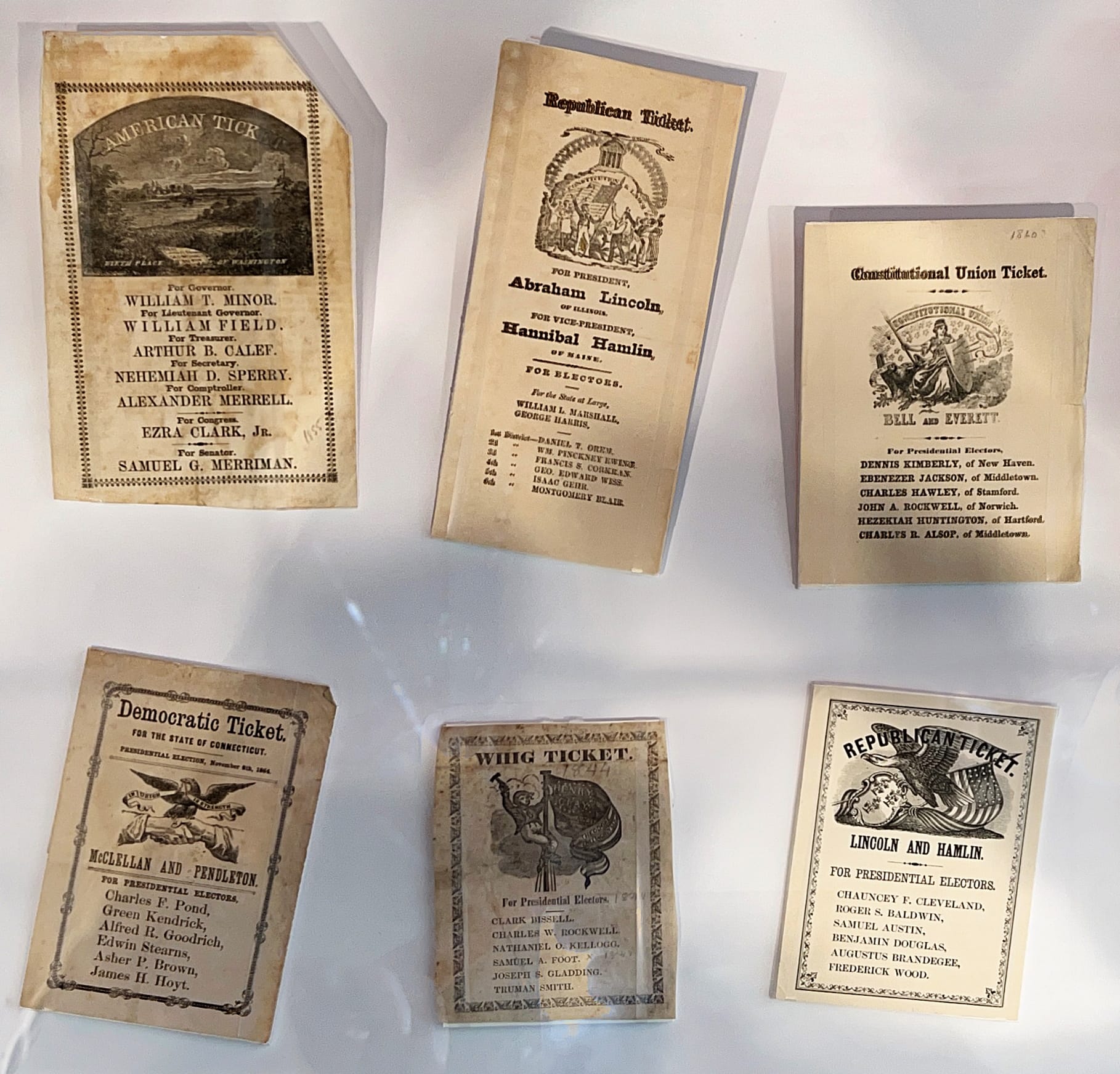

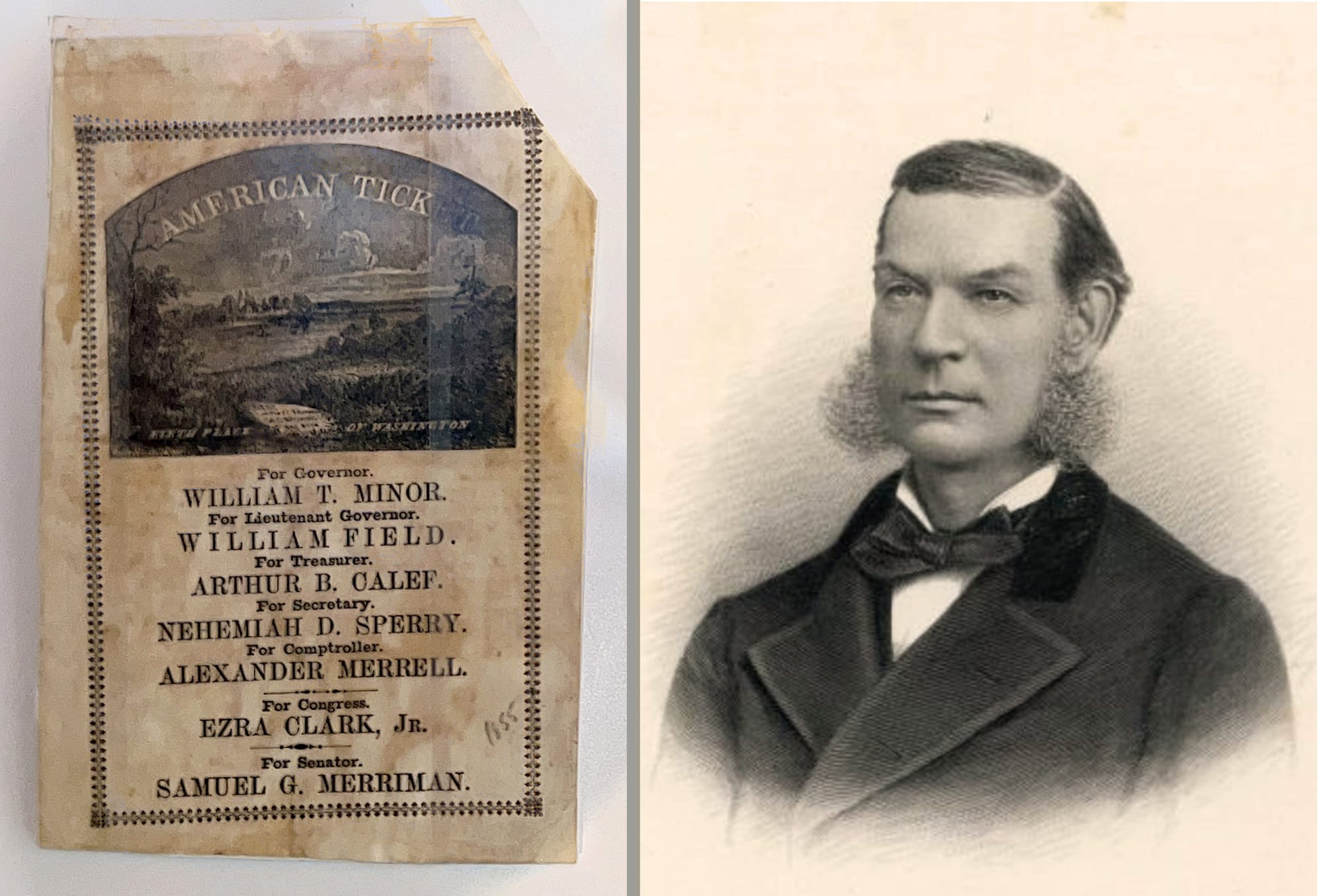

At the entryway to the exhibit, an array of artifacts from political campaigns that led up to the dramatic presidential election of 1860 were showcased. In this display I was surprised to see a familiar name pop out at me — none other than Woodbridge's very own Nehemiah Day Sperry (1827-1911), listed as a candidate for Secretary of the State of Connecticut on the “American Ticket.” Members of this ticket won election, and Nehemiah served from May 2, 1855 to May 6, 1857 under William Thomas Minor, the 39th Governor of Connecticut. (Fun fact: our current, 89th Governor, Edward Miner (Ned) Lamont, Jr., is Gov. William Minor's 5th cousin, five times removed.)

Various campaign tickets on display, the American Ticket of 1855, and candidate for Secretary of the State, Nehemiah D. Sperry at about this time.

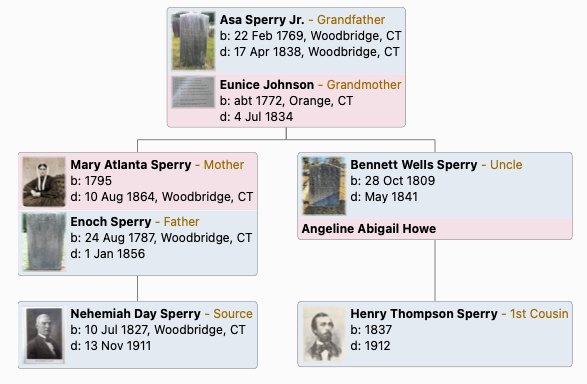

Seeing the start of Nehemiah's political career set in this historic context (he went on to serve as U.S. Congressman from 1895 to 1911) got me thinking about what may have motivated him to seek office. As I looked closely at the Sperry family tree (and of course, consulting ‘That Great Sperry Family’ where this line of the family appears on page 27), it turns out that Nehemiah and Henry Sperry were first cousins, through Nehemiah's mother's side of the family. Surely, they knew each other as contemporaries.

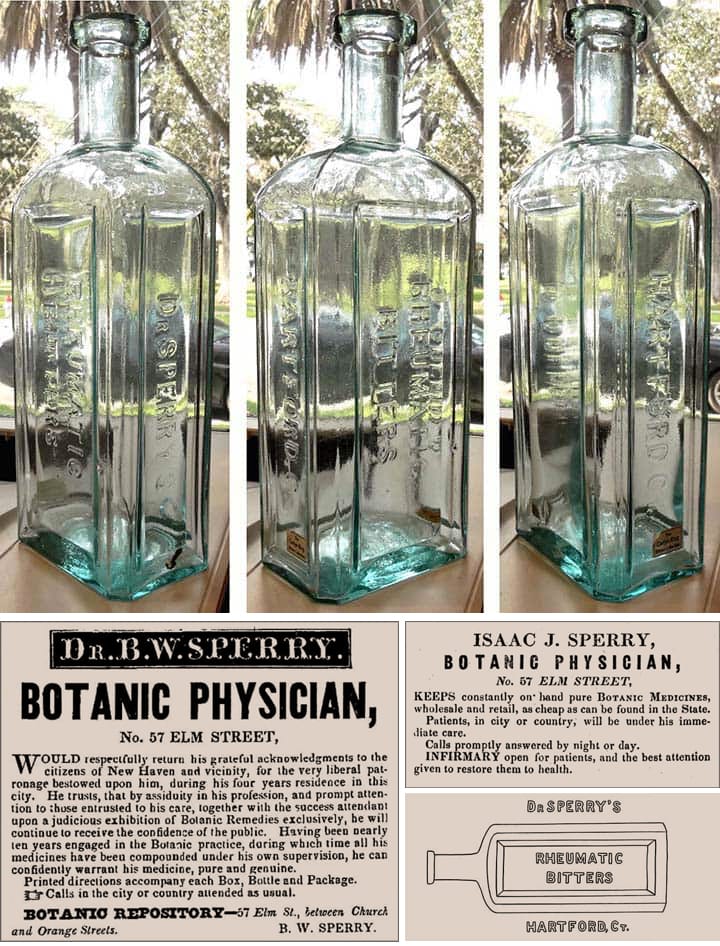

This branch of the Sperry family in Woodbridge headed by Asa Sperry Jr. (1769-1838) and his first wife Eunice Johnson Sperry (1772-1834) included Nehemiah's mother Mary Atlanta Sperry (who lived in the house that once stood in today's Sperry Park, as I've written about in a prior essay) and Henry's father Dr. Bennett Wells Sperry, as well as two other brothers who became prominent adherents of something that was known as Thomsonian medicine, a popular form of alternative medicine in the early 19th century founded by Samuel Thomson (1769–1843). It was based on the belief that disease was caused by a disruption of the body’s natural heat and could be cured by restoring the body’s internal balance using botanical remedies included cayenne pepper, bayberry, and ginger, often administered in teas, poultices, or steam baths.

Doctors such as the brothers Asa Ellsworth Sperry (1805-1843), Isaac Johnson Sperry (1801-1871), and Bennett Wells Sperry (1809-1841), who were trained in Thomson's methods, were seeking to democratize medicine by empowering ordinary people to treat themselves and their families using his methods, which were straightforward and inexpensive. His approach rejected the professional medical establishment, which he viewed as elitist and harmful, and criticized the prevailing medical practices of the time, such as bloodletting, mercury treatments, and calomel (a mercury-based purgative), which these botanical doctors considered dangerous and unnatural.

According to an article titled “The Thomsonian Movement, the Regular Profession, and the State in Antebellum Connecticut: A Case Study of the Repeal of Early Medical Licensing Laws” by Toby A. Appel, the Sperry brothers figured prominently in efforts to democratize healthcare and reflected a broader reformist spirit:

“...the real organization of the movement in the state began in 1835, led by the brothers, Bennett W and Isaac J. Sperry. Bennett Wells (B. W) Sperry, born in the New Haven area in 1809, became acquainted with the Thomsonian system in 1829 and trained by working as a student and assistant to Thomas Lapham, an established Thomsonian practitioner in Poughkeepsie, New York. Lapham recalled that Sperry was twice attacked by cholera during the 1832 epidemic and "was rescued by the timely application of Thomsonian remedies." Sperry obtained a "diploma" from the Dutchess County (N.Y.) Botanical Society in December 1831. In 1833 he was practicing in Unionville, New York and in 1835, with Dr. Abial Gardner in Hudson, New York. Both Lapham and Gardner were active in organizing Thomsonians in New York, and were thus role models for Sperry's leadership of the Thomsonian movement in Connecticut.

Sperry returned to New Haven at about the age of twenty-six in late 1835 at the request of a local Thomsonian physician Samuel Richardson, who had considered giving up his practice due to his wife's ill health. Richardson, an agent of Thomson who had arrived in Connecticut in 1833, founded a Thomsonian infirmary and built up a flourishing practice. In January 1835, he organized the New Haven County Thomsonian Botanic Medical Society with nine right holders as members. Sperry purchased his infirm ary and began to treat patients in the city and surrounding country. As of 1837, he boasted in his journal, The Thomsonian Advocate, that he had introduced the Thomsonian system into 140 New Haven families and almost as many families in the surrounding towns. Unlike the regular physicians, who considered it unethical to advertise, Sperry published testimonials for his skill, a list of heads of families of patients (which included several lawyers and clergy men), and advertisements for himself and other Thomsonian prac titioners. To assist him, he trained a number of students in botanic practice. Sperry's older brother Isaac J. Sperry, initially a skeptic, was won over by his brother, and he, too, became a practitioner, locat ing by 1837 in Hartford.14 Although the Sperrys had purchased family rights from Samuel Thomson, they were not his designated agents

Bennett Sperry died in May 1841 of pulmonary consumption before legislative victory was achieved. Immediately after victory, Isaac Sperry and his colleagues prepared for the next stage of development of botanic medicine, namely meeting with other botanies in New England... While he had broken with Samuel Thomson in 1838, he continued to define his practice as Thomsonian. With the assistance of his son, T. S. Sperry, he wrote his own textbook in 1847, The Family Medical Advisor, recommending it "to the Thomsonian family generally throughout the New England States. The Connecticut Botanico-Medical Society continued to meet under the old 1848 charter past Sperry's death in 1872, until 1883 when it folded for lack of a quorum.”

Mary Atlanta and her physician siblings Asa, Isaac, and Bennett, would also have been well-acquainted with their forefather Richard Sperry's role harboring the Regicides and his strong sentiments in favor of Oliver Cromwell who ruled as Lord Protector of the Commonwealth of England after King Charles I's execution in 1649. Their father Asa's grandfather, Jonathan Sperry, was about two-years old when his grandfather Richard died in 1698.

As was the case for many other Puritan settlers of the New Haven Colony in this time period, Richard Sperry likely came here from England seeking religious freedom and a desire to live in a society aligned with his religious and political ideals. The founders of the New Haven Colony were strict Puritans who were viewed as more radical than their counterparts in Massachusetts Bay Colony as they sought to create a theocratic society based on their interpretation of biblical law. Nonconformists — those who rejected the Church of England’s control — were among the most common emigrants in this era. Richard's decision to risk his life to hide the fleeing judges Whalley and Goffe when Charles's son was restored to the throne in 1660, reflects a strong moral conviction and independent thinking consistent with nonconformist beliefs. It's therefore safe to say that Richard was more of a 'Roundhead' than a Cavalier, as these two sides in the English Civil War were known.

By the 18th century, New Light revivalist movements (part of the Great Awakening) carried forward the dissenting spirit of earlier nonconformists, emphasizing personal morality and challenging entrenched hierarchies. Some of Richard and Dennis Sperry's descendants born in Woodbridge shorty before the American Revolution — as Henry and Nehemiah's grandfather Asa Sperry Jr. was — may have been adherents to this New Light thinking that focused on ideals of equality and individual responsibility and helped spur social and cultural changes, including challenges to established authority in both church and state. These New Light sentiments may have also gone on to influence their family members to align themselves with abolitionist or anti-slavery ideals of the Wide Awakes as part of their family's long-standing tradition of challenging injustice and advocating for reform.

Richard Sperry's defiance in harboring the regicides reflected the ideals of his fellow Puritan settlers in the New Haven Colony. These ideals of moral responsibility and challenging injustice seem to echo through the generations, influencing the family’s later alignment with reformist and abolitionist movements. From Richard's nonconformists values, to the trio of brothers who pioneered botanical medicine, to Henry and Nehemiah's involvement in the early days of the Republican Party’s anti-slavery platform, members of the Sperry family have championed reformist movements across the centuries.