Spinning a Bethany tale from 1923 — Made from whole cloth

In December 1923, American headlines were filled with scandal and upheaval. President Calvin Coolidge, still new to office after the sudden death of Warren G. Harding, had just delivered the first-ever radio-broadcast State of the Union. The nation was grappling with the fallout from the Teapot Dome scandal, one of the most notorious cases of political corruption in U.S. history. Prohibition was in full swing, fueling a growing black market and daily headlines about raids, speakeasies, and organized crime.

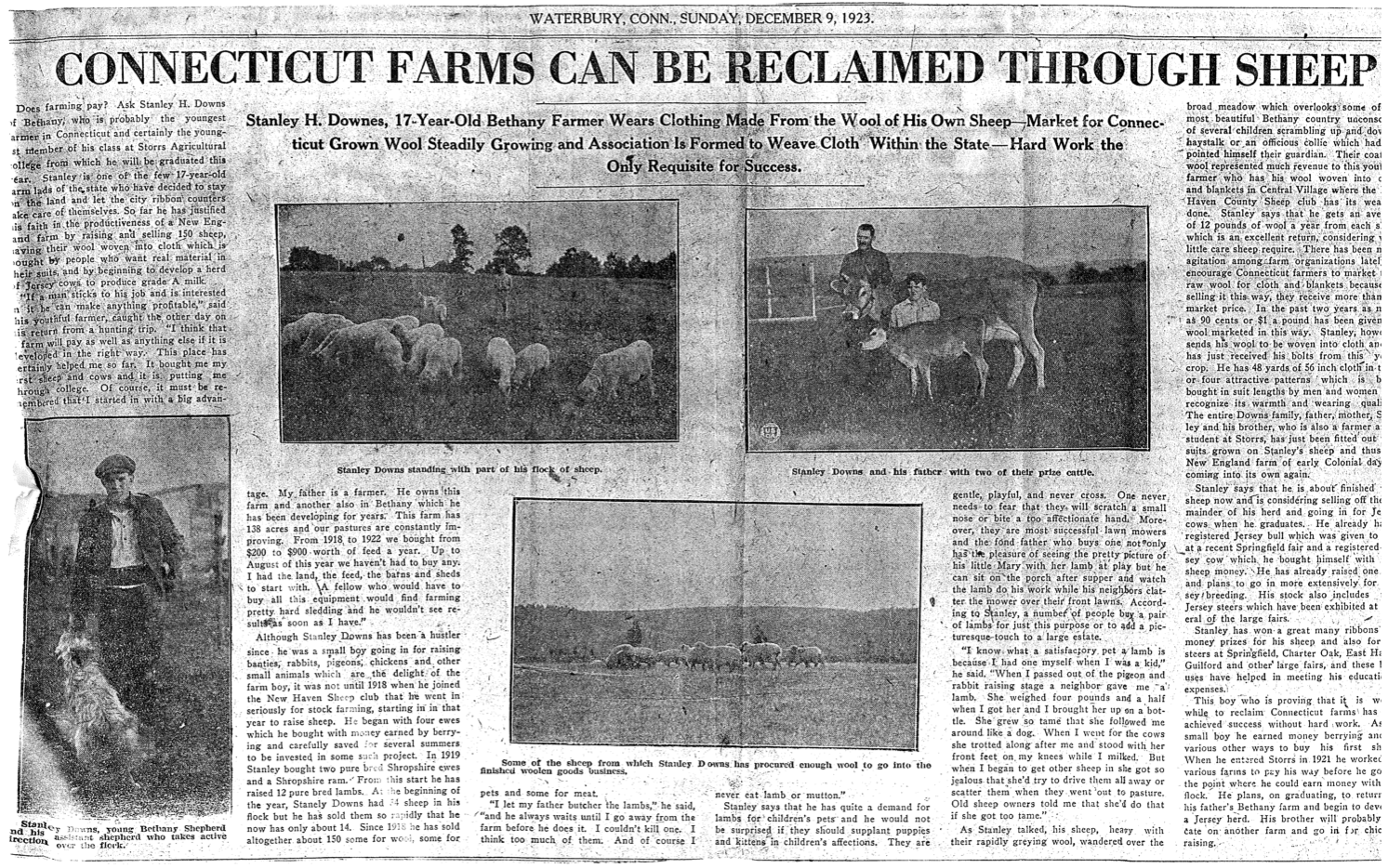

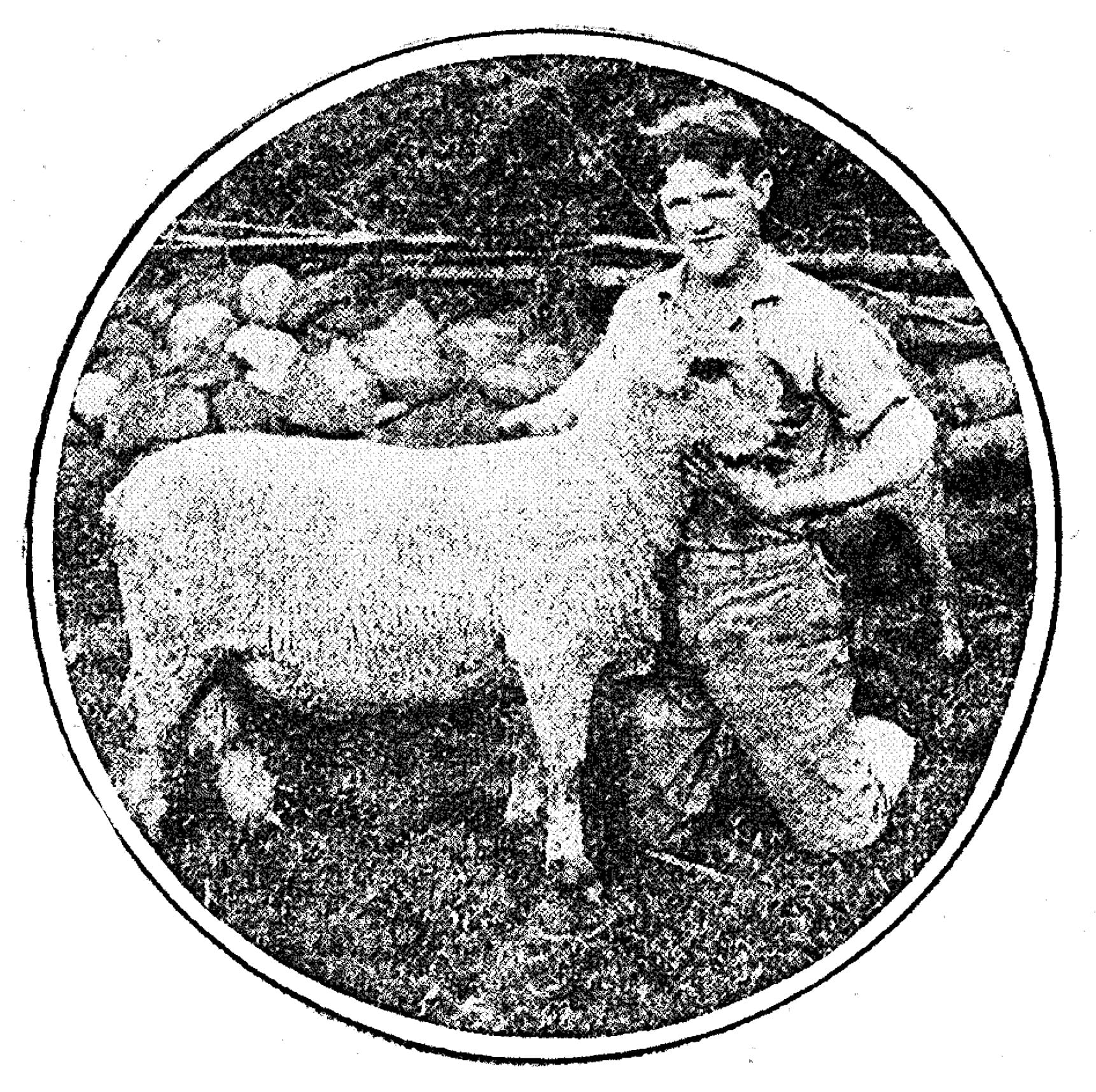

And yet, tucked quietly into the Waterbury Republican, a very different kind of story appeared. No crime. No corruption. Just the story of a 17-year-old boy from Bethany, Connecticut — Stanley Hotchkiss Downs (1906-1963) — reclaiming abandoned farmland, raising award-winning livestock, and even having suits tailored from the wool of his own flock of sheep.

A century later, this article reads like more than a profile. It feels like a blueprint: for sustainable land use, youth empowerment, and local resilience. And at its heart is a story still worth telling — about how young people were doing more than following the news. With a handful of lambs, and a little help from the 4-H movement, they were rebuilding the land beneath their feet.

Known to his family as Tucker, Stanley Downs' story was a celebration of a different kind of American spirit: resourcefulness, patience, and care for the land. Destined to serve as Bethany First Selectman in the early 1960s, at the time of this article he was a student at the Connecticut Agricultural College, which would later grow into the state’s flagship public university — the University of Connecticut (UConn). In the 1920s, the college was a hub for youth agricultural programs and rural innovation, serving as a launching pad for students committed to improving their farms, families, and communities.

The article also notes that Tucker was a member of the New Haven County Sheep Club, and he had not only raised over a hundred sheep — he had their wool made into suits for his entire family. In a year of national disillusionment, Tucker was proof that the quiet work happening in small towns still mattered.

One of the most remarkable aspects of Tucker’s story is how his efforts quite literally clothed his family. As the 1923 article noted, Tucker had not only raised a flock of sheep and improved his land — he had enough wool processed to make custom clothing for his entire family.

His father, Jerome Andrew Downs Jr. (my own great-great-grandfather) who had recently concluded his time as Bethany's First Selectman, is pictured proudly in a tailor-made wool suit, the final product of their farm’s full-circle economy. It’s a striking image of self-reliance and rural ingenuity: from brush-covered land, to pasture, to sheep, to wool, to suit. In an era long before today's ‘fast fashion’ these suits were a statement—not of wealth, but of resourcefulness, pride, and craft. Tucker's family wore their labor, quite literally, on their sleeves.

The story of the Downs family and their homegrown suits gains added dimension when viewed in the context of Bethany’s early industrial history. Though Tucker raised and sheared his sheep in the 1920s, the echoes of his family's deeper roots in local wool processing were still present in the landscape.

Just a short distance from the Downs family farm on Litchfield Turnpike in Bethany lay the remains of the Sperry Mill, an 18th-century waterfall-powered facility once used for grinding grain and processing wool. Though no longer active by Tucker’s time, the mill had been a vital part of the local agricultural economy. In fact, by 1907, the Sperry family heirs had already gifted the land — including the old mill site and the original Sperry home lot — to the town of Woodbridge to create what is now known as Sperry Park.

Tucker’s connection to the mill wasn’t just topographical, it was genealogical too. Simeon Sperry (1739-1805), a Revolutionary-era farmer who operated the mill in the late 1700s, was Tucker’s second cousin six times removed. This lineage of stewardship, independence, and land-based labor carried forward through the generations in the Downs family, as Tucker reclaimed brushy hillsides with sheep and wore suits sewn from his own wool.

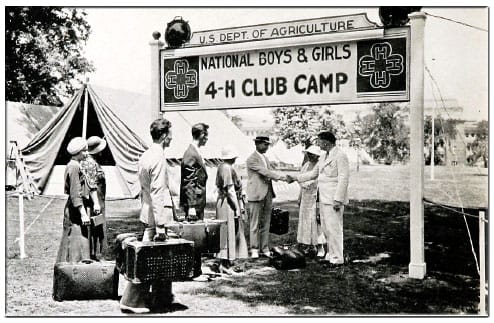

Another interesting aspect of this 1923 news article is what it tells us about community organizations of the day. In the early 1900s, 4-H wasn’t yet the national organization we know today, but its foundations were firmly taking root in Connecticut. Youth clubs were flourishing under the guidance of the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Extension Service. A 4-H retrospective published in 2002 recalls:

“By 1915, there were 3,129 boys and girls enrolled in 11 types of clubs, all part of the USDA’s Extension Service work. These included corn, potato, poultry, and sewing clubs. The goal was to teach farm youth to become more productive in agriculture and home economics through hands-on experience.” — 4-H Youth Development in Connecticut: 1952–2002

More than a century later, 4-H continues to build on that legacy with youth agricultural clubs such as the Amity 4-H Club, which serves the community in Bethany and Woodbridge. This modern chapter of 4-H fosters hands-on learning and leadership development for local youth, just as early sheep and poultry clubs once did. While today’s members may focus on topics ranging from environmental science to robotics, the core values remain the same — Head, Heart, Hands, and Health. To explore how 4-H is thriving in our community today or to get involved, you can learn more by visiting the website of the UConn 4-H Youth Development Program.

Vintage images from the Eastern States Exposition — known today as the 'Big E'

The article also tells us that in fall of 1923, Tucker attended the Eastern States Exposition. Founded in 1916 with the goal of promoting agriculture, industry, and youth education across the six New England states, the Exposition was held annually on fairgrounds in West Springfield, Massachusetts. It featured displays of innovations in the farming industry and held contests designed to encourage farmers to improve through competition. Youth competitions were organized in partnership with the Boys & Girls Clubs of America, awarding prizes for best produce, jams, breads, raised hens, planting techniques, and other categories.

By the early 1920s, an eight-day camp program was established at Springfield's Camp Vail for all youths who placed first or second in judged competitions. These gatherings helped inspire a generation of civic-minded, skilled young farmers —including Tucker, who was honored there for his achievements in sheep farming.

In 1967, the Eastern States Exposition became popularly known as The Big E, reflecting its expanding scope beyond agriculture into entertainment, food, and regional culture. Today, it’s still held each September in West Springfield, drawing nearly 1.5 million visitors annually.

While boys like Tucker were reclaiming pastures in Bethany, the article also notes that a young woman named Louisa Schlagel of North Guilford was quietly making history in her own right. A mill worker by morning and shepherdess by afternoon, Louisa joined the sheep club in 1918 with a single lamb. Just five years later, she had built her flock to fifteen—and she wasn’t done yet:

“Louisa says that she does not intend to stop until she has a flock of one hundred head.”

Balancing industrial labor with livestock care, Louisa was part of a generation of young women who redefined what was possible on small farms, even before they had the right to vote as adults. Her ambition extended beyond the pasture — she also excelled as a livestock judge. This short tribute in the 1923 article recognizes not just her skill, but her determination in a male-dominated field. It's a reminder that the 4-H and agricultural youth programs of the time quietly elevated girls into roles of expertise and leadership, even as broader society lagged behind.

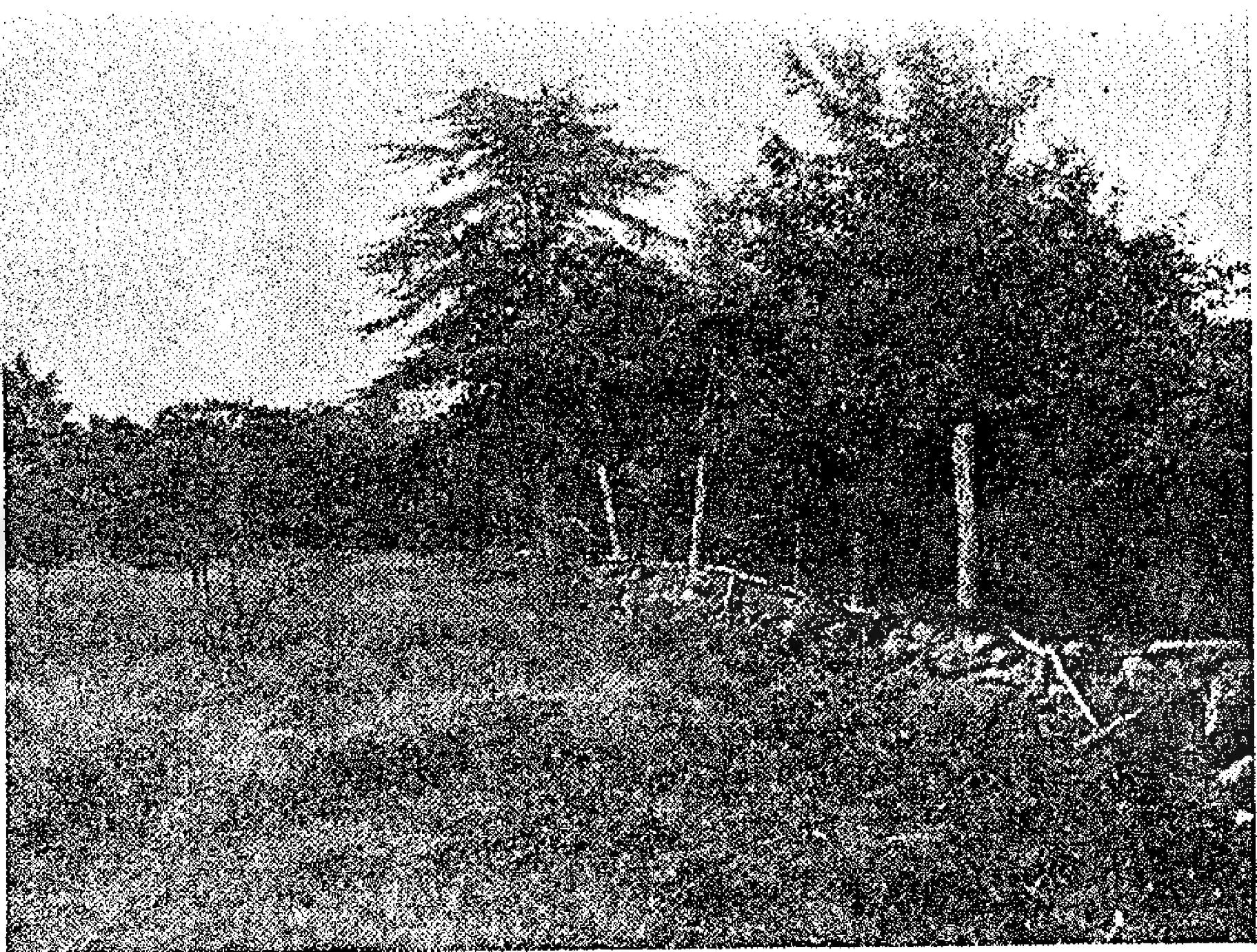

Tucker with one of his flock alongside an image of one of his pre-improved fields.

One final lesson for today from this 1923 article is found in the description of the techniques these young farmers are practicing — what today we’d call regenerative land management. As the 1923 article explained:

“The fields where he keeps his sheep were all like the thicket on the right side and in the background of the picture. Stanley cut the brush, burned it, and turned in the sheep.”

This simple but effective method transformed overgrown land into productive pasture, saving the Downs family up to $900 a year in feed costs. In fact, by August 1923, they had purchased no feed at all—everything the flock needed came from improved grazing practices.

Tucker wasn’t alone in this. Another Bethany farmer, Joe Benning, also returned to sheep farming in 1923 after seeing the success of local youth clubs. His flock not only restored his fields — but eliminated poison ivy, an early example of what’s now called targeted grazing. In one charming aside, the article noted:

“They are most successful lawn mowers... a number of people buy a pair of lambs for just this purpose or to add a picturesque touch to a large estate.”

The story of Joe Benning’s farm in 1923 offers more than a quaint anecdote — it’s a case study in sustainable land restoration. As the article describes: “Joe is transforming a brushy waste into good pasture ground by hard work and his sheep.” What Joe observed back then — sheep naturally clearing poison ivy and brush — aligns closely with modern ecological grazing practices. Today, conservationists and land stewards are rediscovering this method as an alternative to chemical herbicides or expensive mechanical clearing. Programs across the U.S. now use targeted grazing to:

- Control invasive plants like mugwort, bittersweet, multiflora rose, and yes, poison ivy

- Reduce fuel loads in fire-prone areas

- Restore open spaces and pasture land

- Promote biodiversity by managing successional growth naturally

What was once novelty — using lambs as gentle lawn mowers — is now part of serious ecological planning. Across New England and beyond, public lands and orchards are bringing back grazing livestock to maintain grasslands, reduce invasive species, and promote biodiversity—without machinery or chemicals.

Just like Tucker, Joe, and Louisa, we might also wonder: What can animals teach us about land stewardship? It seems a few lessons from 1923 still hold true today—sometimes the best tools for restoring balance to the land have four legs and a good appetite.