Back in the days of farming along Johnson Road

What was life like in the days before mechanized farm equipment and modern methods of food storage, when the farmers of old Woodbridge cultivated so much of the land that has become the leafy residential neighborhoods throughout the town of Woodbridge? As Edward Clark describes his neighbors along Johnson Road he paints a picture of farm life for us:

“On the corner of the Ansonia Road, as I have said, lived Daniel C. Augur. Before the beef from Chicago there was quite a large number of butchers in and near New Haven, who supplied the market. Some of them I remember. Rogers Platt lived in a little house where the Plymouth church on Chapel street now stands, and if I mistake not he had a slaughter on the corner of Edgewood Avenue next above. Truman Alling, after whom Truman Street was named, had one where the St. Bernard Cemetery now is. William Bronson had one where the St. Laurence cemetery now is. He had a farm as many of them did in connection with his butchering business, and I remember the fat oxen lying at ease on the hillside, waiting their turns. There were two of these slaughters on my road two miles below.

I asked my father how these men managed their products before the days when ice was used. He said they would butcher towards night, and during the night the meat would cool and would be put upon the market the next day, and that which was not immediately consumed would be put into brine. Corned beef and pork were the staple articles of diet in New England in those days. The farmers who didn't “put down their own” would buy in quantity. Mr. Charles Agur told me his father had a perennial order which he filled once a year for Uncle Asa Alling who lived a mile and a half below, and sent him each year to deliver a barrel of beef. One year when he arrived with the beef Uncle Asa told him he would not need it that year for he had a whole barrel left over from the previous year.

In those days drovers would start through the country with a herd of cattle, stopping for rest and feeding where the occasion offered. All along farmers would buy from these herds cattle to turn into their pastures to fatten for slaughter in the fall or early winter. Sometimes a drover would own a farm where he would pasture and sell out his stock during the summer. The farm previously mentioned, formerly owned by Cap'n Andrew Clark, was later owned by S. Harwood and used for this purpose.

But in my day ice was used as this local butchering continued, although to a lesser extent for some years after the western beef was coming in. I think the last time my father fattened cattle for market was in the year 1881. About the turn of the century my uncle butchered a pair of fat oxen and put the meat on the benches of his merchant son for immediate consumption. But immediately complaints began to come in in abundance. The meat was too tough. One epicure lamented that he had lost his dinner that day. The meat had not ripened enough.”

That's certainly a colorful description of the meals that families in Woodbridge consumed in the olden days. But in the late 1800s and through the early decades of the 20th century, people continued to rely on the ways of their ancestors. A description of 'the country kitchen' appears in Hazel Lounsbury Hoppe's book, “Bethany Pebbles & Flowers” and sheds some additional light on this subject by describing how her mother Nellie Downs Lounsbury (1890-1960) prepared the family meals in the 1920s:

“A word should be said about the pantry, that necessary adjunct to the kitchen. Our pantry must have been typical of those in the old homes, and since I lived in a few of those ancient houses in Bethany, in my memory all pantries seemed to have characteristics in common. Ours was a small, narrow room with a window at one end and shelves along the sides. ... I still recall the scents in the pantry-a lingering aroma of spices stored there and the smell of newly baked pies or cakes that often were set to cool on the shelf by the window.

Refrigeration as we know it today was far in the future. In those frigid winters the pantry was cold enough to store and preserve almost any food. My older sisters recall the times when the closed-off front hall served as a locker for frozen food. Long before Clarence Birdseye, my father discovered the method of preserving by freezing. One winter he hung a side of beef in the unheated small front hall. Soon the meat was frozen solid. A small hatchet was employed to lop off a bit of beef now and then and the family enjoyed steaks and roasts all winter.

The summer months were a different story. I do not recall any use of ice during those years at the Denzil Hoadley house. Sometimes food was stored down in the cool cellar in the heat of summer. Other times when food required cold storage, a strong rope was tied to a closed container that was hung down the well on the hill. Since we did not use that well for drinking purposes, it was apparently a proper custom.

Although our milk was carefully stored in the well, sometimes it did not get used in time and turned sour in spite of the cold well water. I suppose that is why so many of the old recipes called for sour milk. There are recipes for sour-milk cake and cookies in my mother's cookbook, for the old-time thrifty Yankees found uses for everything that came their way.

When the sour milk was not used in other ways it was allowed to develop into curds and whey. My mother called this "loppered" milk. This mixture was poured into a square of clean cloth and tied into a bag to allow the whey to drip out. I remember the bag, hung outside on the clothesline to drip. When the curds had separated enough, Mama poured it into a bowl and seasoned it, and we enjoyed homemade cottage cheese, or Dutch cheese as we sometimes called it.”

Back on Johnson Road in Woodbridge, Edward Clark provides a few more details of the houses between the former land of Captain Andrew Clark (where the Sorensen family later farmed) and the corner of Johnson and Ansonia roads. He says:

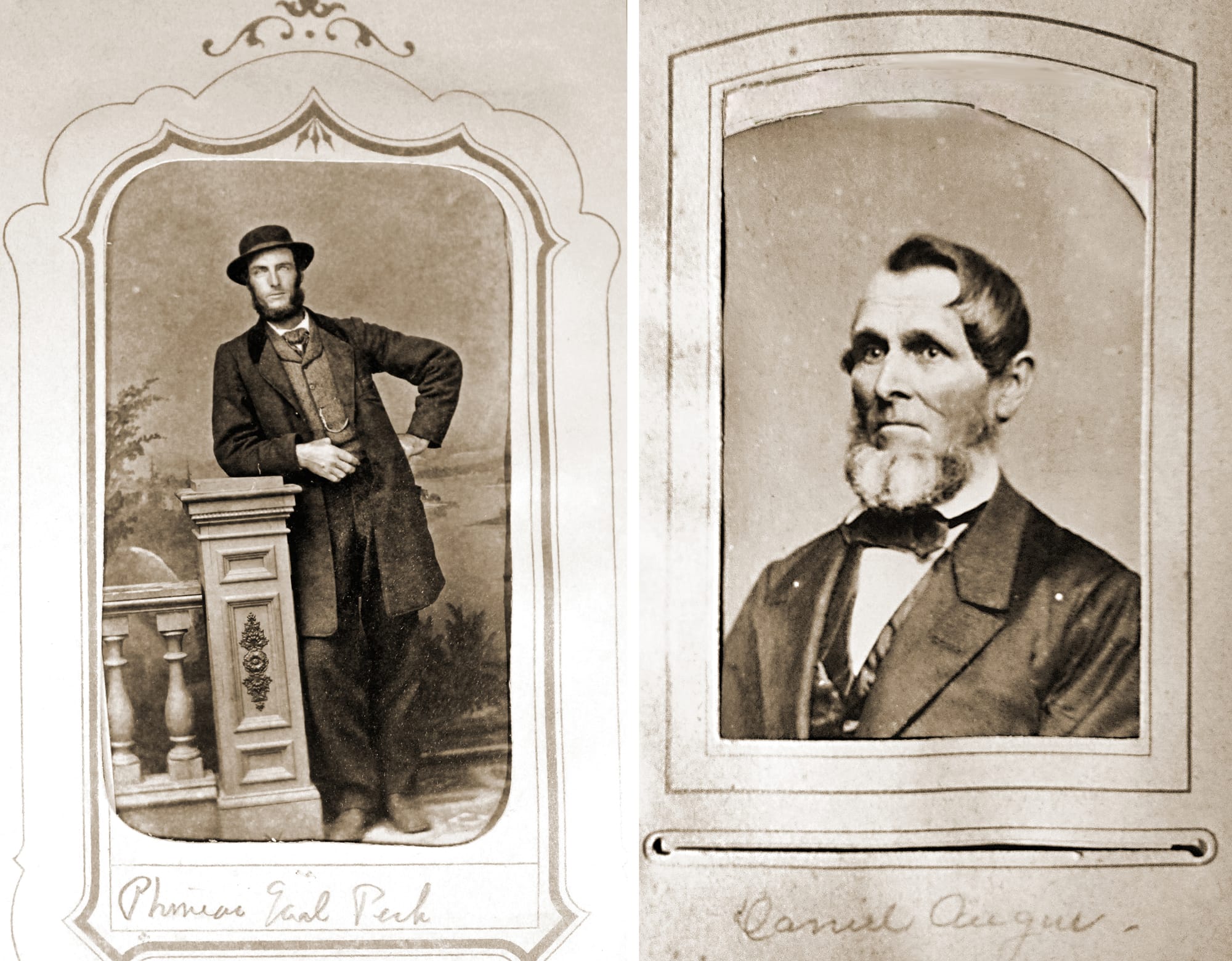

“On the next place above, Phineas E. Peck [1832-1929], uncle of the late Silas J. Peck, told me he and his father and mother, who was afterwards called “Aunt” Adeline, were living in 1835, when his mother’s father, Ephraim Baldwin, died, and they immediately moved to the Baldwin homestead. In my boyhood days the place stood idle. We called it the Wren Place. It was allowed to depreciate for years until Errold Augur bought it and repaired it, making a nice home of it.”

The men mentioned above are connected by marriage. One of Phineas's daughters, Adeline Peck (1873-1964), married Daniel Auger's grandson, Erroll Meredith Auger (1874-1927) — likely the 'Errold Auger' that Edward says has purchased and renovated the old Wren Place next door to his grandfather. The family of Irish immigrant Hugh Wren lived here through 1887 according to the book "Historic Woodbridge" in the entry for the house at 1150 Johnson Road:

“Historically associated with Irish immigrants during the nineteenth century, this house was built by Timothy McEvoy c. 1840 on land he purchased from the property of Willis Ball, who then lived next door. During the Civil War the seven-acre property was owned by James Baldwin, but he sold it in 1867 to Ellen Wren (1822-1868). Ellen was the wife of Hugh Wren (1809-1882) and they both were born in Ireland. She died the following year but Hugh continued to live here with his young family. In the 1870 census, although listed as a farm laborer, he owned the house and had a modest personal estate. In his household at that time were Mary (13) and William (10). Charles, the older son born in 1859, did not live at home. William inherited the property when his father died, but sold it five years later to another Irish family from New Haven, the McKennas. Ellen McKenna passed it on to Wells Beecher in 1894 and in 1900 the property, conveyed that year to Edward, the sole Beecher heir, was immediately sold to Erroll Augur. Augur, who then also owned the old "Thomas Place" next door that had earlier encompassed this property, passed both parcels, totaling 17 acres, on to his son, Minott, who conveyed them in 1923 to the Jacksons.”