Forged from the earth: The cement kiln and the spirit of industry in Woodbridge

The ruins of the old cement kiln off the Litchfield Turnpike have long been an object of quiet curiosity — a relic tucked away in the woods, its story half-remembered or forgotten altogether. When I learned that a local hike was being organized to visit the site this weekend, it seemed like an opportune moment to finally dig deeper into its history.

Researching the kiln led me to the men who once staked their hopes on it: Fordyce Durgy, Robert McIntire, and Ebenezer Benton Beecher. Fordyce and Robert appear first in the 1873 land records securing property from the Sperry and Peck families for the operation. By 1878, as their New England Cement Company's fortunes declined, Ebenezer Benton Beecher — a businessman with family ties to Woodbridge who lived in Westville — emerged more directly, acquiring interests once held by Durgy and others, consolidating ownership of the site's leases and associated rights.

Today, some looking back have wondered whether the kiln was a doomed venture from the start, or even a deliberate scam. But contemporary accounts — including those of Congressman Nehemiah D. Sperry, who knew the men and the place well — tell a different story: one of earnest effort, dashed by economic forces beyond their control. What began as a simple search to understand a ruined kiln unfolded into a larger story of families rooted deep in New Haven Colony soil, of dreams forged from the rocky landscape, and of the enduring spirit of industry that still echoes through our community today.

The roots of the Beecher family run deep, from the rocky hills of Woodbridge to the streets of the neighboring New Haven village of Westville. From the very first days of New Haven Colony, the Beechers — alongside the Sperrys, Hotchkisses, and other early families — helped build a community grounded in industriousness, ingenuity, and civic spirit.

Anson Beecher (1805-1876) was born in Watertown, Connecticut to Wheeler Beecher (1755–1838) and his second wife Mary 'Polly' Hotchkiss Beecher (1763–1848). Wheeler Beecher derived his name from his mother's family name; his parents were Caleb Beecher (1722-1784) and Abigail Wheeler Beecher (1723-1768), who were born in Woodbridge and raised their family here. They are buried at East Side Burying Ground on Pease Road, nearby the final resting place of Caleb's father, Captain Ebenezer Beecher (1686-1763).

In his youth, Anson worked as a schoolteacher, but soon turned his inventive energy toward manufacturing. He is credited as the first person in the United States “to plait or weave a straw hat” and he produced the first solid head pins manufactured in the United States. After marrying Nancy Benton (1803-1884), Anson spent several years in Morris, Litchfield County, before relocating to Westville in New Haven in 1853. There, he founded A. Beecher & Sons, a match manufacturing firm that would grow into the Swift, Courtney & Beecher Company and, eventually, the Diamond Match Company — the largest match manufacturer in the country. Anson Beecher’s inventive drive and entrepreneurial success laid a strong foundation that his sons would carry forward in New Haven and Westville.

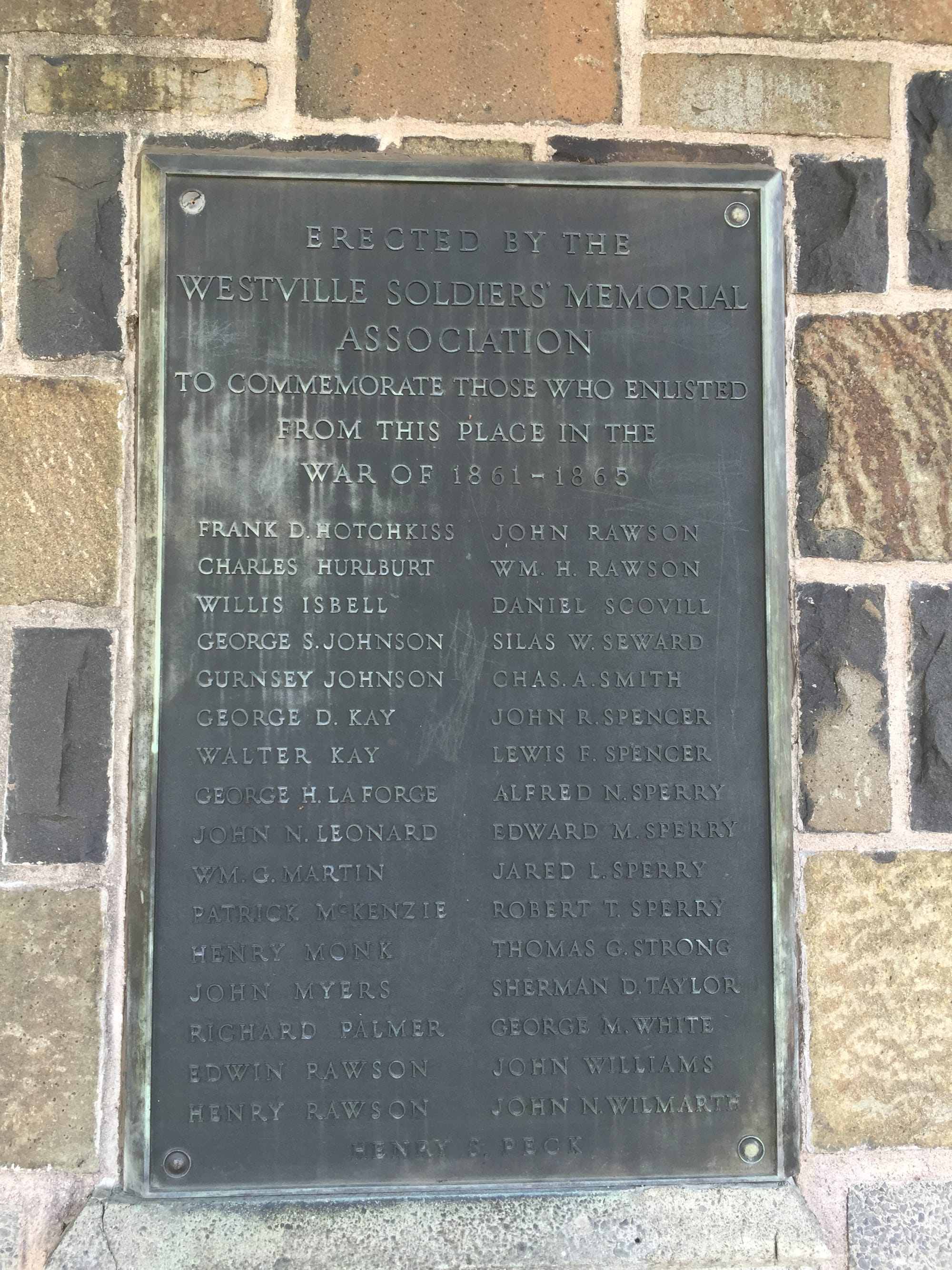

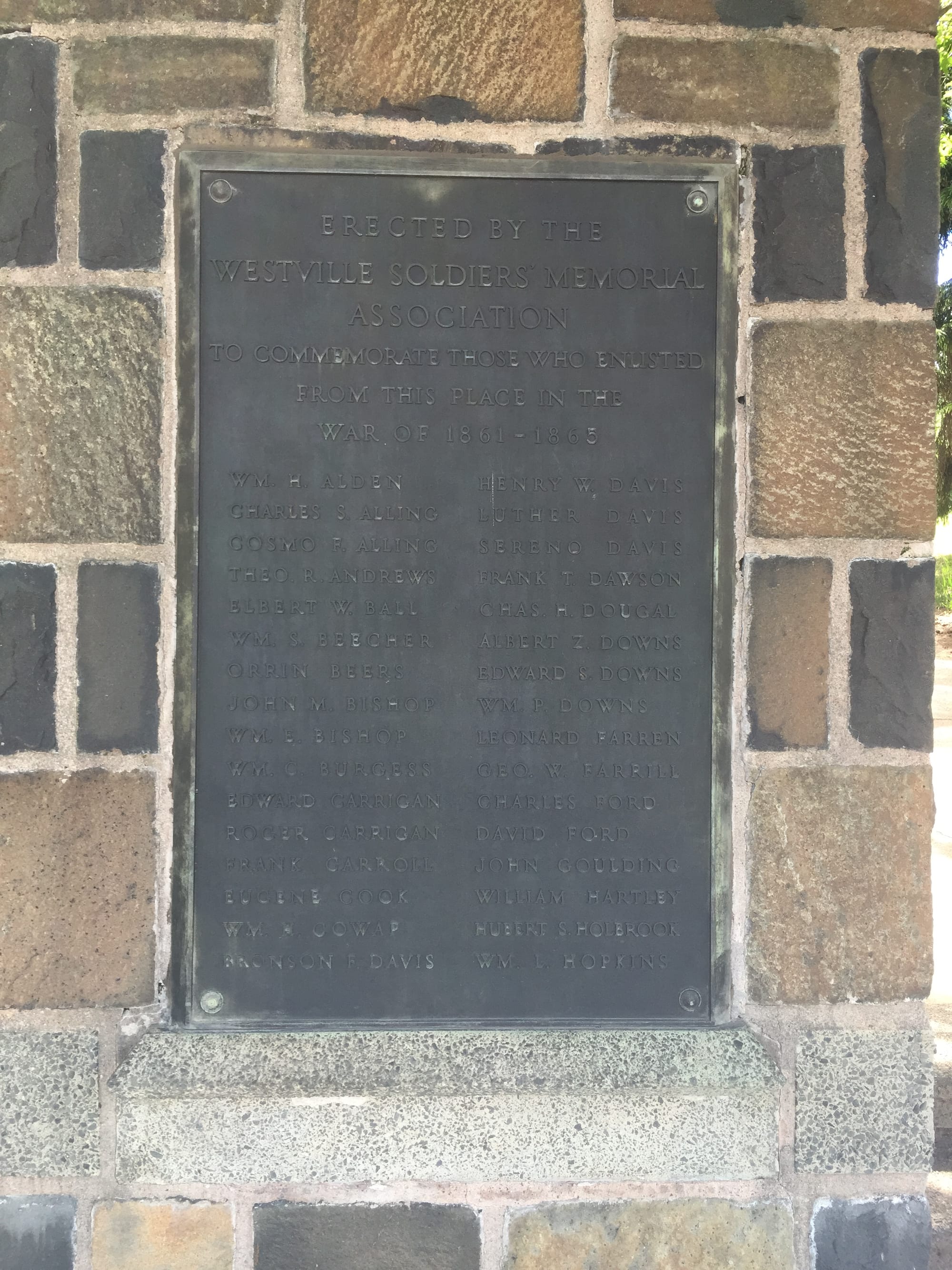

Anson and Nancy's four sons — Ebenezer Benton Beecher, Lucius Wheeler Beecher, Lyman Anson Beecher, and William Skinner Beecher — embodied the continuation of this Woodbridge legacy. The firstborn, Ebenezer Benton Beecher (1830–1904), for whom Beecher Park is named, was associated with his family's manufacturing business along the West River in Westville, as well as the Geometrical Tool and Greist Manufacturing companies. He also invested in far-reaching ventures that sought to transform raw material into the lifeblood of a growing nation during the industrial revolution. His brother L. Wheeler Beecher (1836–1920) rose to prominence as president of the Geometric Tool Company, at a time when the precision manufacturing firm helped New Haven emerge as a center of innovation. He also devoted fifty years of service to the city’s school board, and is today commemorated through the L. W. Beecher Museum Magnet School of Arts and Sciences in Westville. The youngest brothers, Lyman Anson Beecher (1837–1920) and William Skinner Beecher (1839–1922), both served with distinction in the Civil War. William, wounded at Antietam, went on to serve the civic life of New Haven as a member of the Board of Selectmen. Together, the Beecher brothers built on the foundation laid by their father, helping to shape the industrial, civic, and military fabric of their community.

At the entrance to Beecher Park in Westville, the Soldiers' Memorial Gateway, dedicated in 1915,

Ebenezer's business partner Fordyce Durgy (1835-1918) also came from a family deeply rooted in Connecticut’s colonial history. While his father, Francis Durgy, descended from Welsh ancestry, his mother, Hannah Wanzer Durgy, was a granddaughter of Anthony Wanzer and Mary Stephens Wanzer, whose mother Mehitable Peck Stephens was a descendent of the Peck family who were the early settlers of Milford, Connecticut. His maternal ancestors included Revolutionary War Captain Samuel Peck Jr. (1716-1801), Samuel's mother Martha Clark Peck Booth (1685-1747), and her father Ensign George Clark (1648-1734), whose family is memorialized with a monument in the Northwest Cemetery as one of the earliest inhabitants of what is today the town of Woodbridge.

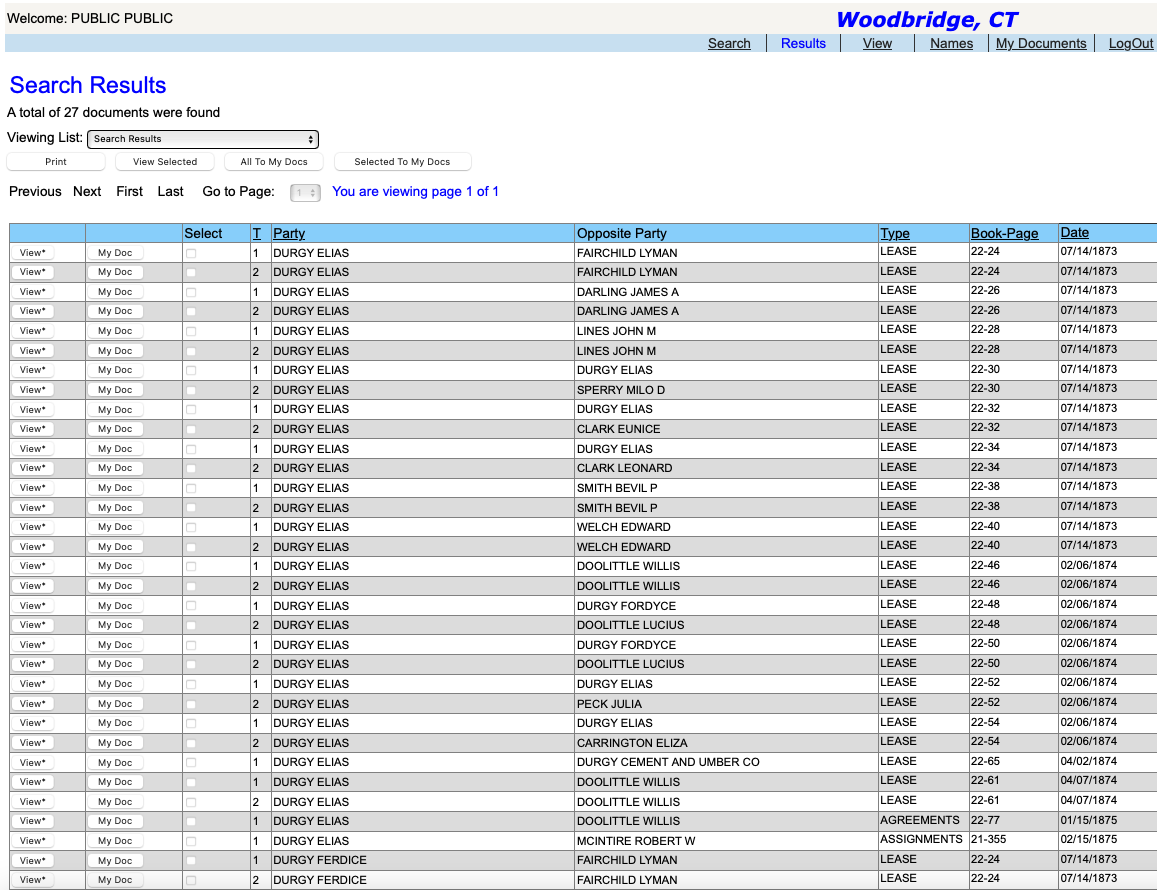

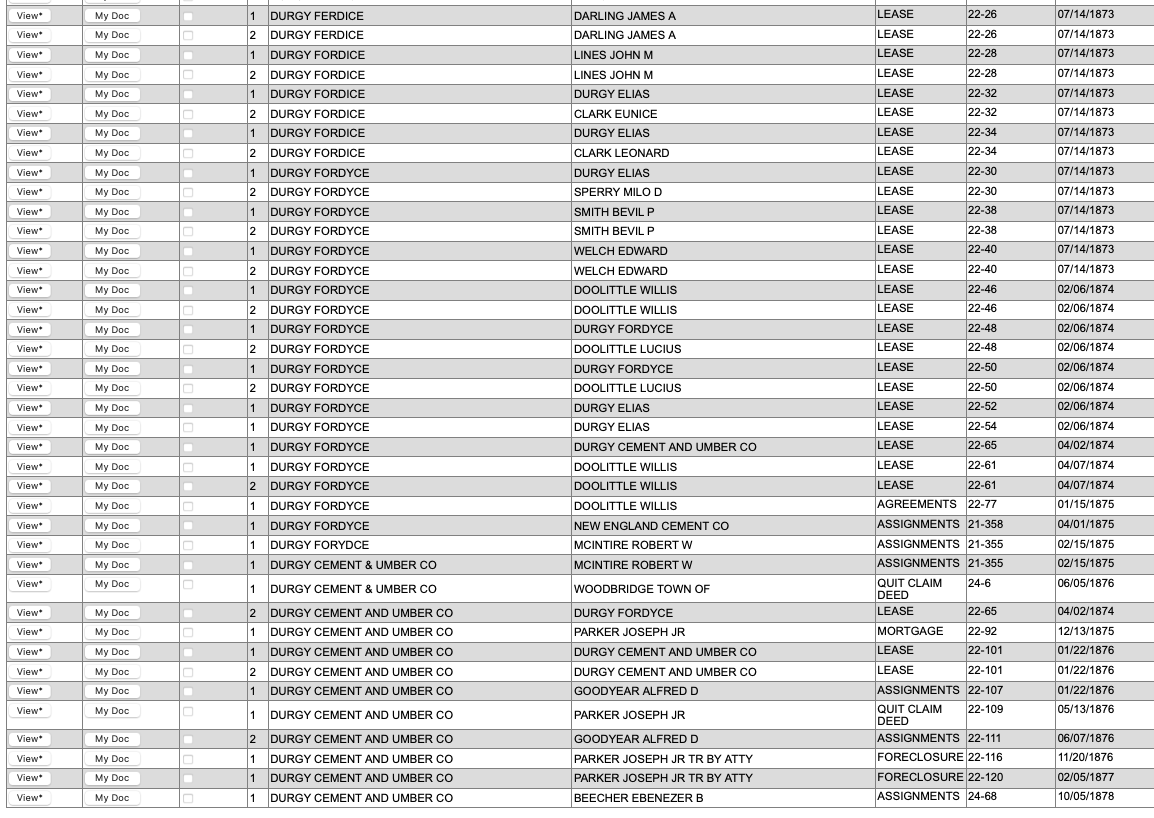

Land records from 1873 to 1876 show Fordyce Durgy assembling a patchwork of leases from neighboring landowners — a veritable 'Who’s Who' of old Woodbridge families, including the Sperrys, Pecks, Clarks, Doolittles, Smiths, and Carringtons — as he and his partners worked to build the infrastructure needed for their cement operation.

Woodbridge land records showing the transactions Fordyce Durgy entered into from 1873-1878.

After the purchase of land along the Litchfield Turnpike and construction of the cement kiln, Ebenezer’s partnership with Fordyce in establishing the New England Cement Company was an attempt to tap into the booming post-Civil War market for construction materials. The need for durable cement was vast, driven by railroad expansion, urban growth, and a national appetite for infrastructure. As the richly detailed History of the Portland Cement Industry in the United States recounts, the 1870s were a time of great industrial experimentation, when men across the country, often at great personal risk, tried to meet the nation's rising demand for building materials.

The Woodbridge kiln, however, faced challenges that ambition alone could not overcome. Natural cement production required precisely the right geological conditions, transportation routes, and milling expertise. Despite their efforts, Beecher and Durgy struggled to achieve economic viability. Period lawsuits, such as Durgy Cement Co. v. O'Brien, illustrate the financial hardships that accompanied early industrial ventures — not as evidence of fraud, but of what appears to be sincere efforts collapsing under daunting economic pressures.

When Congressman Nehemiah D. Sperry visited Woodbridge in 1895, traveling up the Litchfield Turnpike opposite the dam, he reflected on the old cement kiln and its fate. He observed:

"And here we are opposite the dam. Just over there on the hillside are the ruins of the old cement kiln, where twenty-five years ago they made cement from the rocks that are so abundant around it. It was good cement, but the business failed and was killed because cement was a cheap article and because it took off all the profits to cart the stuff to New Haven. Perhaps some day an electric road will come by here and then the business might be profitably worked."

At first glance, Sperry's words might sound merely wistful. But given his deep involvement in business and transportation initiatives throughout the region, it is more likely that he already knew of the growing discussions about building an electric trolley line through Woodbridge. Just two years later, in 1897, a group known as the Friends of the Woodbridge and Seymour Trolley Road formally organized to promote that very idea — a reminder that in communities like Woodbridge, ambition often traveled along well-tended networks of family, memory, and shared purpose. (Learn more about the Friends of the Woodbridge and Seymour Trolley Road in a previous essay.)

Although the cement kiln in Woodbridge ultimately failed, Fordyce Durgy and E.B. Beecher did not abandon their shared ambition. Nearly two decades later, their names reappear together in the records of Virginia industry, this time organizing copper mining ventures in the town of Virgilina and the surrounding border region. Their efforts with the Person Consolidated Copper and Gold Mines Company reflect the same spirit that had animated their work in Connecticut: a belief that wealth and progress could be forged directly from the earth, if only the right opportunity could be seized.

Today, taking part in Earth Day weekend activities in Woodbridge, a small group of us set out to visit the old kiln site. Gathered at the nearby Darling House and hiking up the Blue Trail through Camp Whiting, we came upon the ruins of the kiln and the adjoining pit where raw earth materials were dug out and transported down the embankment to the kiln itself for processing. Quiet now, and overgrown with trees and vines, the site merely hints at the bustle of activity that surrounded it in the 1870s.

Today, a walk through Westville or into the woods along the Litchfield Turnpike, offers quiet reminders of the enduring presence of the men who shaped the development of our community. Hidden among the trees overlooking the old highway, the stones of the cement kiln still stand where their ambition once burned. Down the road in Westville, the L. W. Beecher Museum Magnet School continues the educational mission that its namesake served for half a century. Nearby, at the entrance to Beecher Park, Ebenezer’s former home, visitors can pause at the Soldiers' Memorial Gateway, dedicated in 1915, where William S. Beecher's name is carved in stone alongside his fellow Civil War veterans who once mustered from this community. These are not grand monuments; they are quiet, steady markers — pieces of a larger landscape of memory. In honoring them, we reconnect with the enduring spirit of industry that has shaped our community for generations, and that still calls to us today.