Spring cleaning, from hearth to hard drive

Each year, the arrival of spring stirs something elemental. Across cultures, it is a season of renewal — a time for light to return, for doors to open, and for the old dust to be swept away. Many cultures mark spring by clearing space — both internally and externally — for what’s to come. In Jewish tradition, this kind of cleaning holds deep significance in the preparation for Passover, where the ritual clearing becomes both a physical and spiritual act. Spring is not just a time for tidying — it’s a time for symbolic action, renewal, and starting fresh. More broadly, spring invites a reassessment of what we carry with us and what we can release.

Old Yankee farming culture adds another layer of texture. Here too we find that spring wasn’t just about cleaning; it was about resetting the year’s rhythm: sharpening tools, mending fences, turning soil, clearing out the root cellar, airing out the bedding, scrubbing winter soot from hearth and home.

In long ago days, the new year began in April. In 1752, Britain and its colonies — including the little New England settlement of Woodbridge — adopted the Gregorian calendar, replacing the old Julian calendar. This reform shifted New Year’s Day from March 25 to January 1. As a result, if you had been born in, say, March 1735 ‘Old Style,’ your birthday was now considered March 1736 ‘New Style.’ And if you didn’t keep up with the changes — well, you might be called a fool (especially when March ended and the calendar page turned to April 1).

With these traditions in mind, I’m cleaning house this spring — turning over digital leaves and revisiting a little project that’s been quietly waiting for its moment. I found myself not just organizing files, but sweeping away the digital dust and bringing long-shelved stories into the light. Spring cleaning as both metaphor and actual archival triage.

This project will be a big organizational lift — that’s part of why I’ve put it off so long. But they say “A journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step,” — a quote often attributed (a bit loosely) to Laozi (Lao Tzu), the ancient Chinese philosopher. So it’s time to get started…

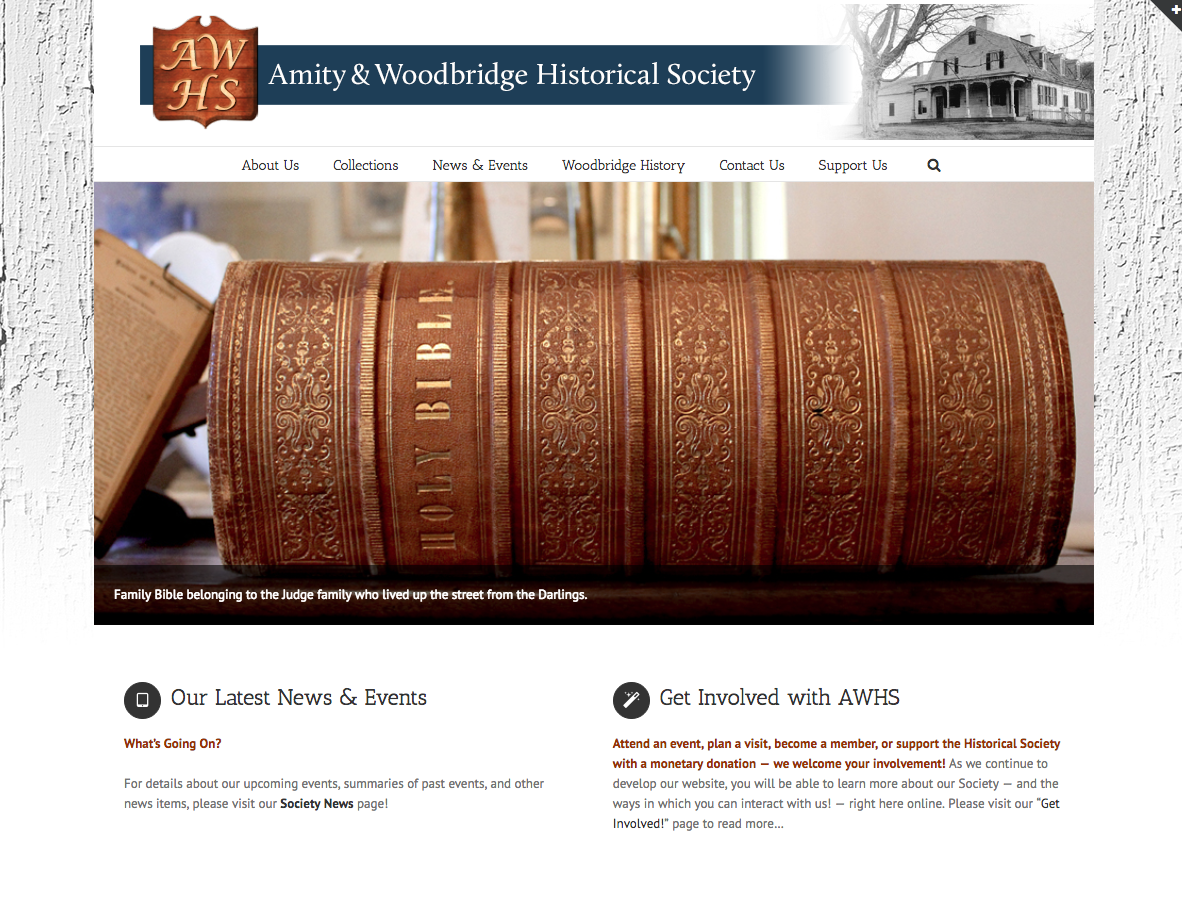

The spark of this project began, as these things often do, with a meeting. A few of us gathered at the Thomas Darling House — creaky floors, history in the walls — one late fall evening in 2013 to begin planning an update to the website of the Amity & Woodbridge Historical Society.

The AWHS website update as planned that evening in 2013.

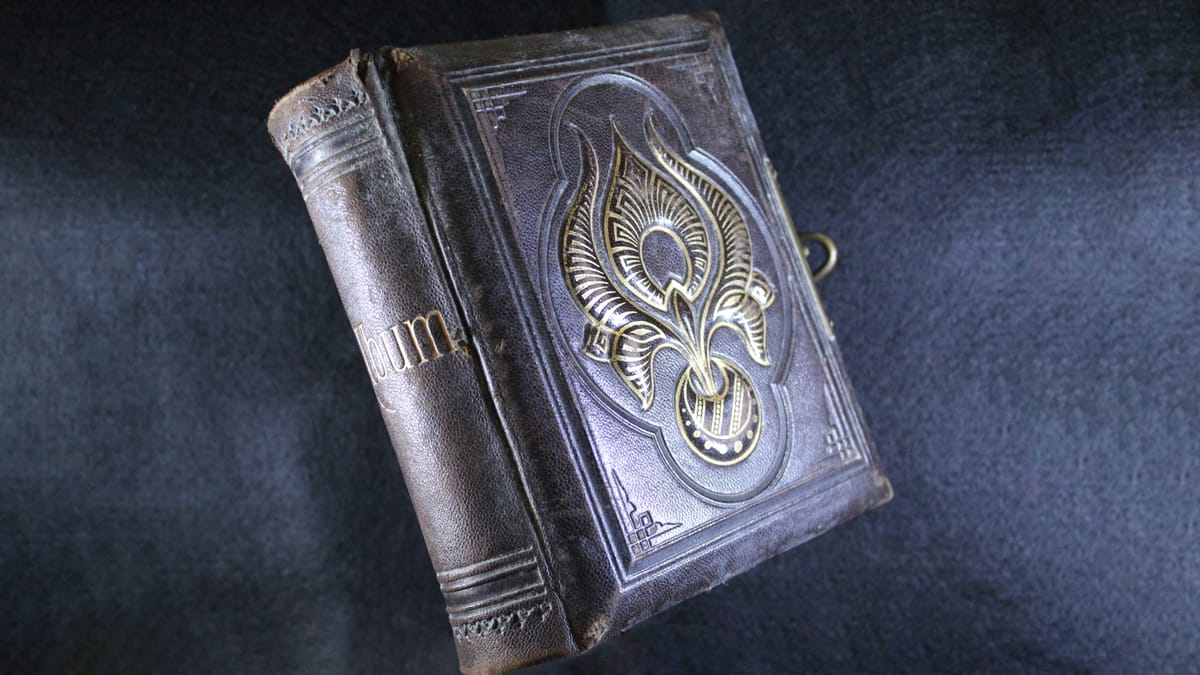

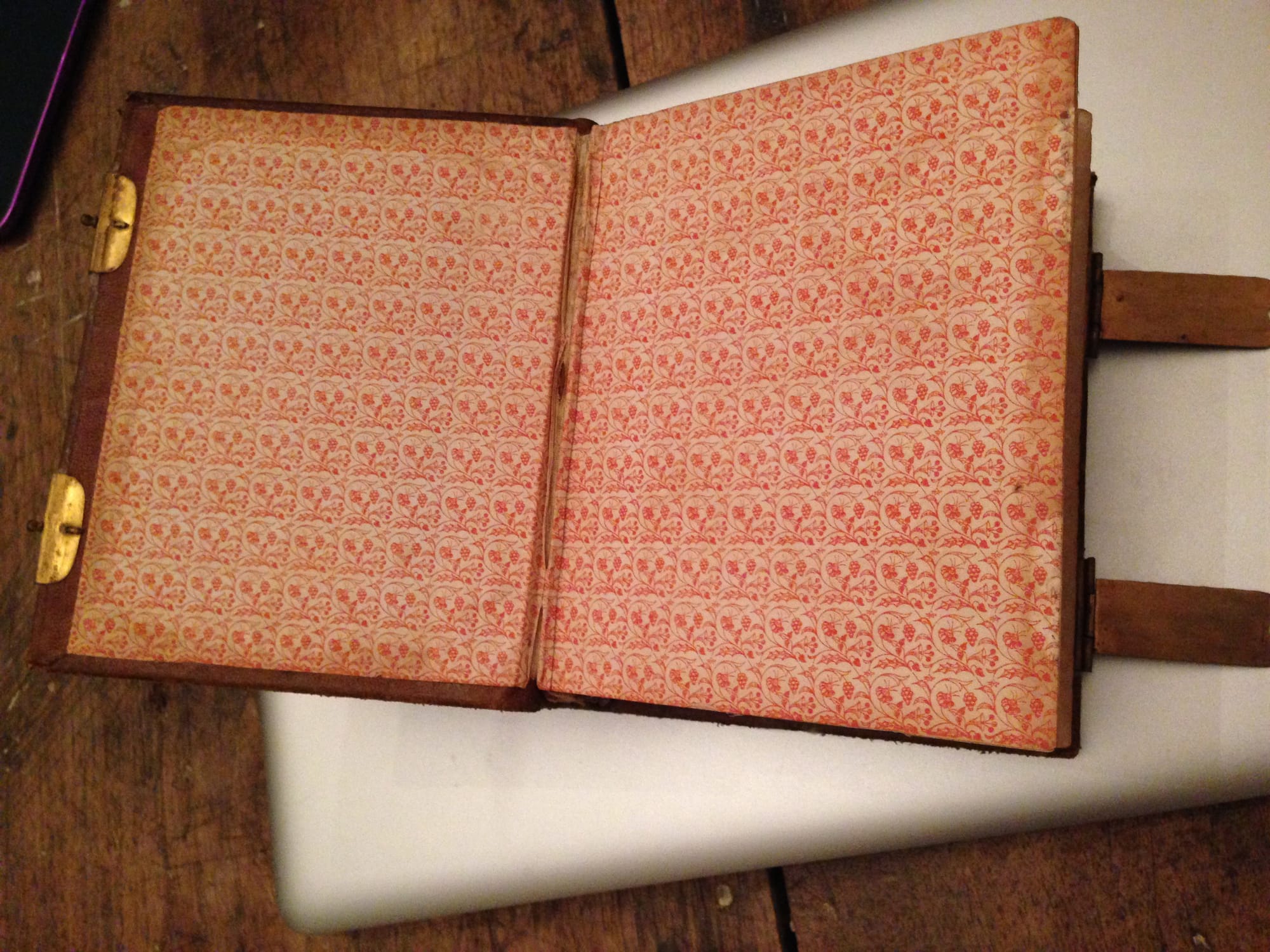

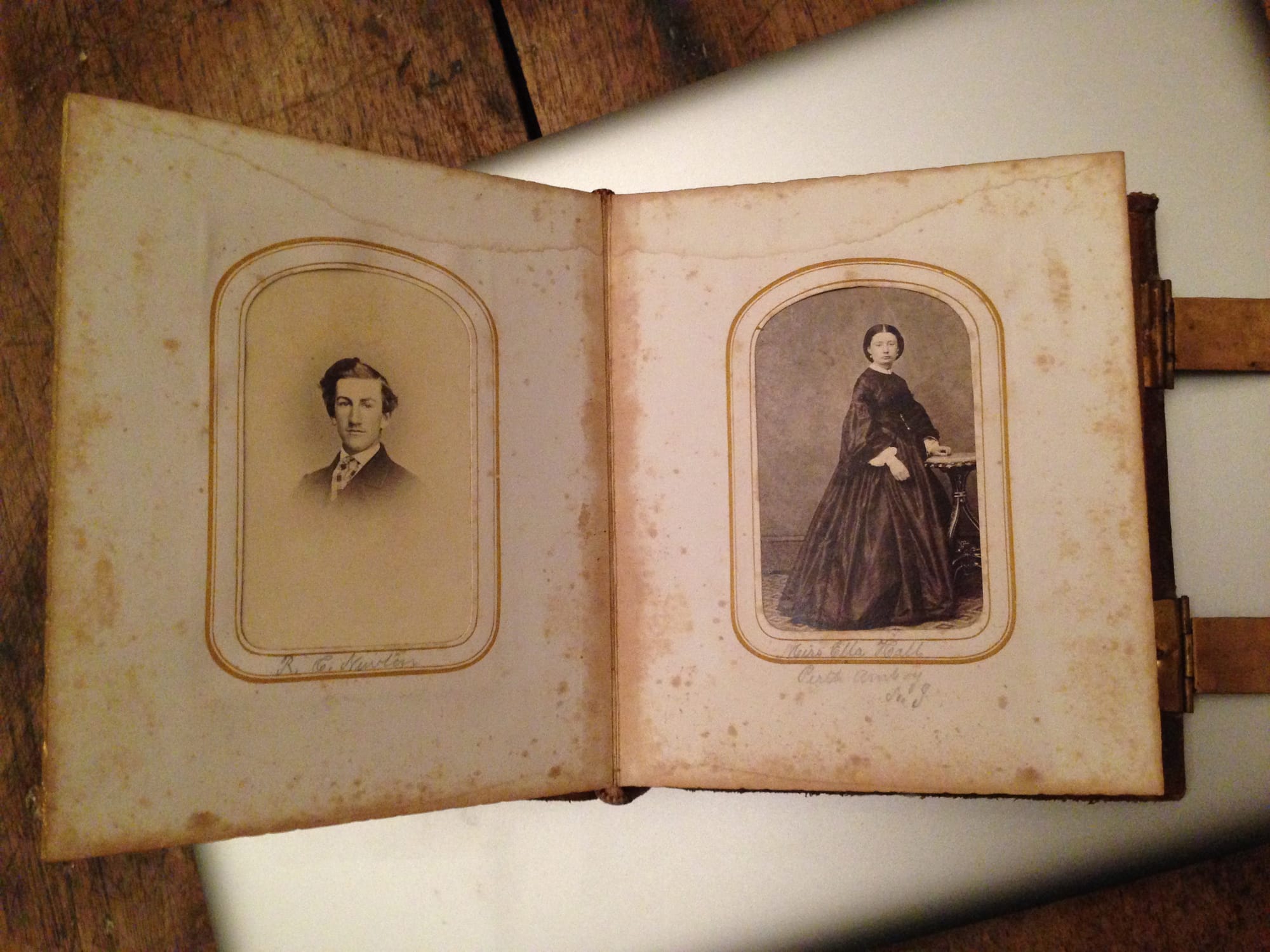

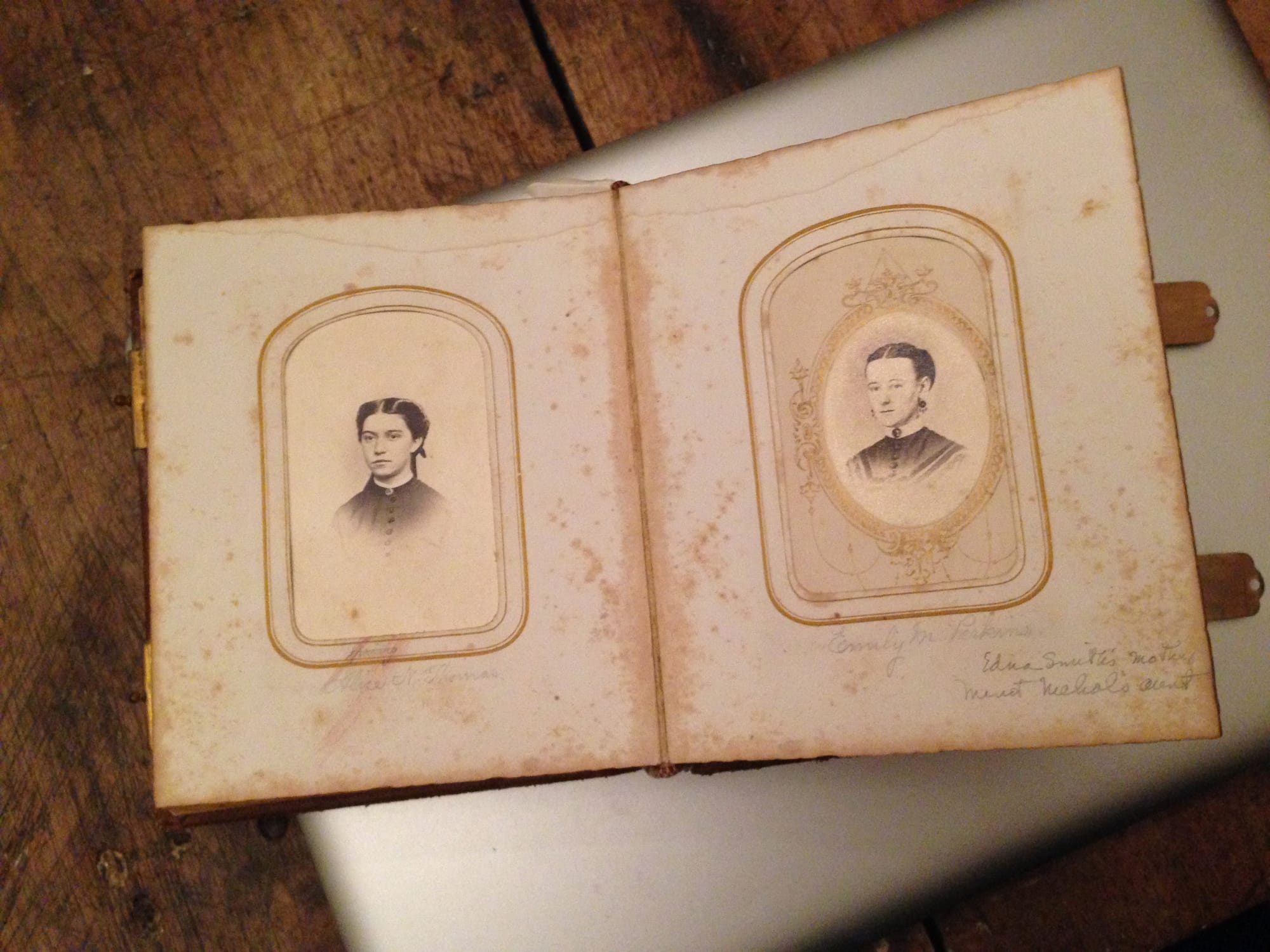

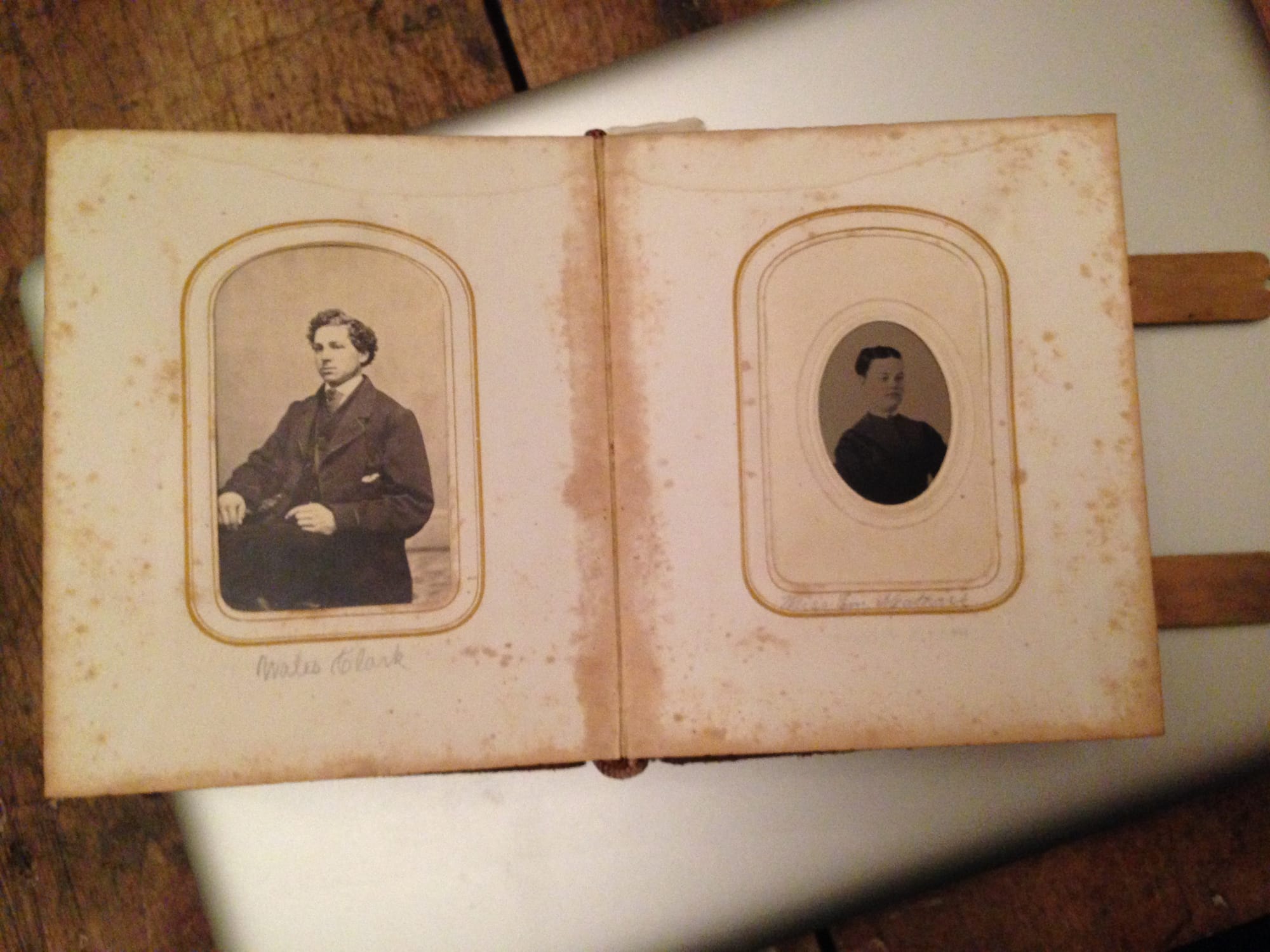

We were a group of neighbors, volunteering our time. We sat around a broad wooden table by the historic home’s hearth. Between slices of pizza and bottles of root beer, someone pulled out a curious album. I remember the feel of it: thick, timeworn, leather-bound. As I sat beside an open laptop, the glow of the Apple logo reflected off the gilt edges of the photo pages. Side by side in that moment were centuries of change — the digital and the analog, the remembered and the forgotten.

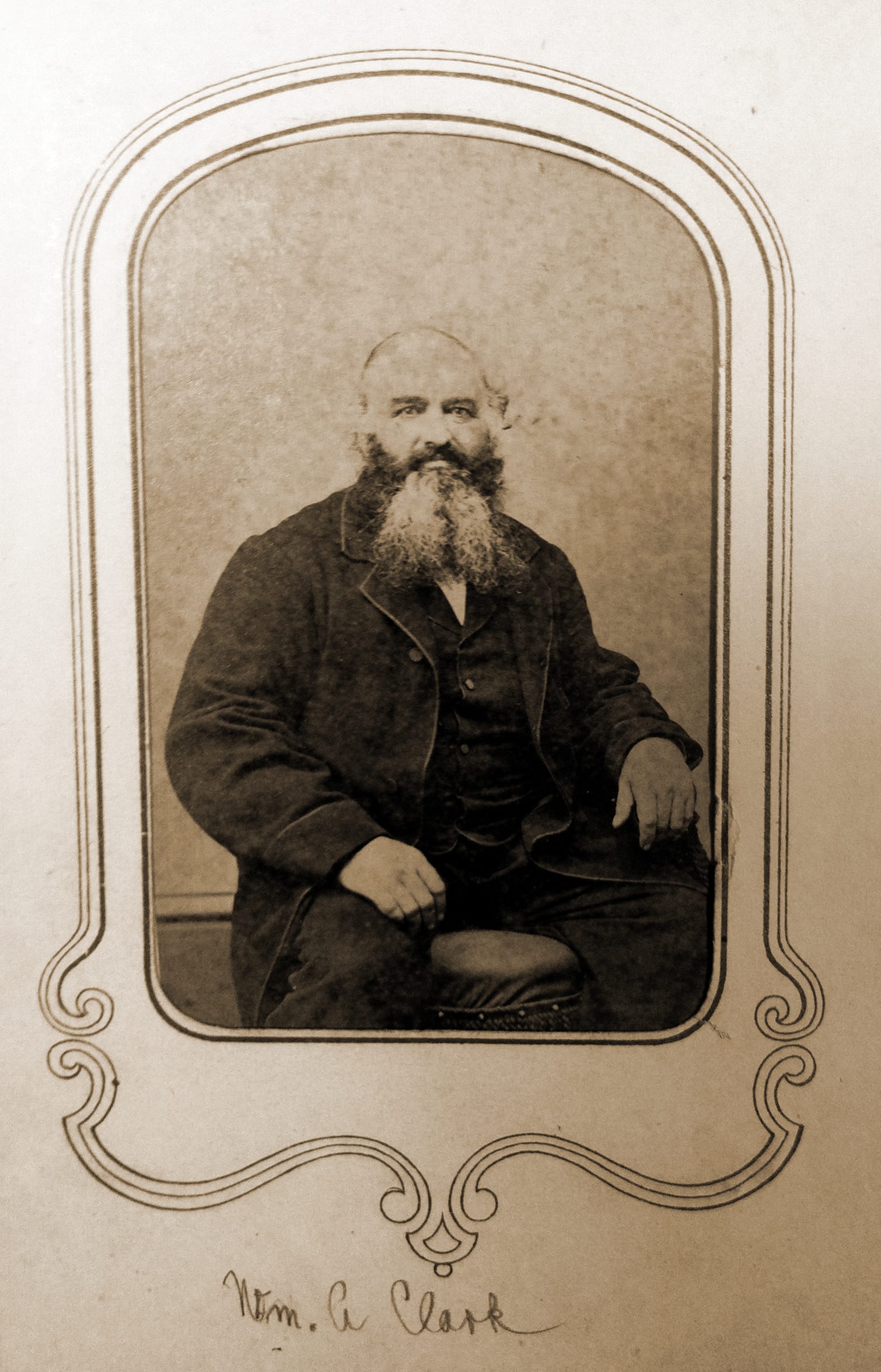

That night, I pored over sepia-toned portraits and inscriptions in looping script. There was William Alanson Clark (1810-1879), whose match company once lit hearths in Woodbridge homes. Someone handed me a small box, delicate and bold all at once. The label read:

“WM. A. CLARK’S

SUPERIOR FRICTION MATCHES

That instantly ignite by being drawn quickly and lightly across the bottom of the box or any hard substance.

WOODBRIDGE, CONN.”

And there was Sila Berenice Baldwin (1883-1973), wearing a prim gingham-patterned dress, seated in a rocking chair on the front porch of the very house we were gathered in — one she would leave to the Town upon her death in 1973.

Earlier that year, the Board of Directors of the Eastside Burying Ground Association had just completed a Boy Scout-led Eagle Scout project to tag the old tombstones in the cemetery on Pease Road. So I recognized the names scrawled beneath the photographs and I realized: many of the people in this photo album are buried there. I thought then about how many of them are related, lying now under the earth like roots — entwining each family connection throughout the little ancient graveyard.

It struck me as a quietly poetic metaphor that perfectly captured what local history feels like when you’re close to it: not just names on stones or faces in albums, but generations of people who are still connected — to the earth where they are buried and to each other, to those they loved and called family — and to us, standing above them, for a time at least.

One of the oddest things about paging through those albums wasn’t how old the photos were — it was how familiar they felt. As I looked at those faces and read the handwritten names beneath each one, I found myself saying things like, “Oh, she married so-and-so, and their son went on to build that house on Racebrook Road.” I realized: this wasn’t just history. It felt less like research and more like remembering. I wondered then if I was one of only a handful of people in modern-day Woodbridge who could decode these fragments and piece together who these people were to each other? (I’ve been building an extensive family tree database for decades — as of this morning, it includes 14,569 individuals — the vast majority connected to old Woodbridge and Bethany families.)

Leaving the Thomas Darling House that night in 2013, I turned to snap this photo. I could almost see Miss Baldwin, seated there in her rocker again.

So with spring in mind, I am thinking anew of the Newton family’s old photo albums — and of all the people whose images are preserved there, and in our local cemeteries. These albums could easily drift into silence, their names and faces slowly fading from memory. But with new tools and technologies — like artificial intelligence — that allow us to analyze and connect photographic images, handwritten notes, and family trees in ways once unimaginable, the time seems ripe to begin a project of cataloging and sharing some of this local history.

What will grow from this fertile soil? Stay tuned for more here at the TownHistory.org website…