Visiting the 'Last Paugassett Settlement' on the border between Woodbridge, Ansonia, and Seymour

In the book, 'History of Seymour, Connecticut with Biographies and Genealogies' published in 1879 by W.C. Sharpe, in a chapter titled 'The Indians' on page 36, the following passage provides some details connecting the native people of Seymour and Woodbridge.

The day of the Indian is passed, and that of the railroad and telegraph has come; yet we do not need to ride or walk far from our daily haunts to find a few mixed descendants of the aboriginees. These are mainly offshoots from the Pequots. They have lived for a long time in a narrow valley where a small stream and a large one unite, a spot which they have named, as Mr. Lossing tells us, Pisli-gacli-ti-gock — "the meeting of the waters." The name on white lips was changed to Scatacook, and the Indians became known as the Scatacook Indians. During a former generation these wards of civilization used to frequent the villages, peddling baskets and small wares to gain a livelihood.

At the beginning of the present century a remnant of the Paugussetts were still living in Woodbridge, bearing the name of Mack, and within a few years some, who were supposed to be their descendants, have frequently been seen in our streets offering for sale the baskets they had made.

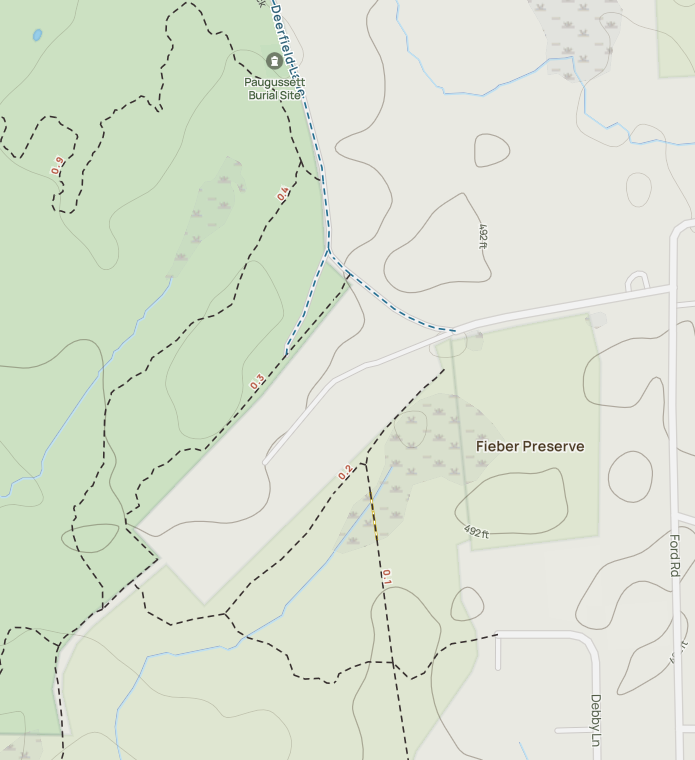

A small group of hikers set out to visit the last known settlement of the Paugussetts on June 29, 2024. We gathered at the cul-de-sac of Debby Lane in Woodbridge and entered the woods on a trail spur located there, that soon met with the trails of the Ansonia Nature Center. Along the way we passed in and out of property marked along the trail with signs indicating State ownership, and eventually we were following the Naugatuck State Forest - Quillinan Reservoir trail as it met the old colonial road known as Deerfield Lane to a clearing marked by two stone pillars.

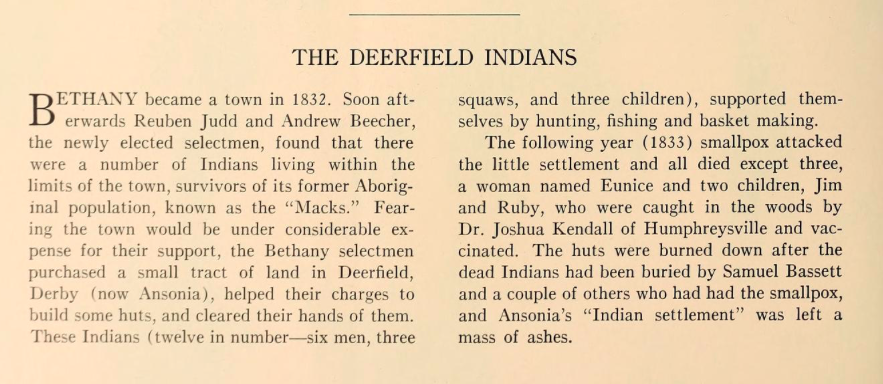

What do we know about the history of this settlement? A 1935 publication, titled "Tercentenary pictorial and history of the lower Naugatuck Valley on the occasion of the 300th anniversary of the settlement of Connecticut" provides some brief background of how this settlement came about — and met its end — in the early decades of the 19th century:

With this description in mind, the group of hikers soon locate the area, enclosed by a fieldstone wall with its entrance marked by two stone pillars, each with a capstone bearing an inscription — the words “Paugassett Indians” on one; and “Last Settlement 1833” on the other.

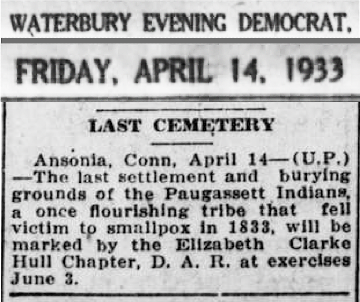

How did these pillars come to mark this spot? To commemorate the centennial of the settlement's demise in 1933, the stone pillars were the work of the Ansonia chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR), founded in 1894. The project was "planned and financed by Mrs. Mary T. Clark." An announcement released on April 13, 1933 noted that previous signs marking the location had not stood the test of time: "The Elizabeth Clarke Hull DAR Chapter will soon mark the Native American settlement and burying ground off Deerfield Lane with stone markers. Previous wooden signs erected there have disappeared. The settlement is on Ansonia Water Company land."

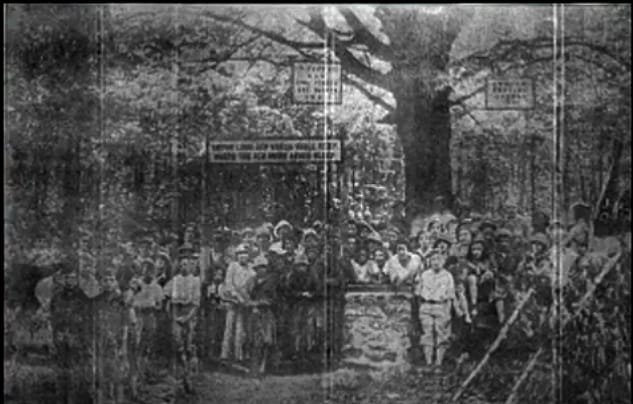

And here is a photograph from the dedication ceremony held on May 27 1933 (note the large tree which has since fallen, but who's trunk still lies directly inside the entrance to the site):

And what became of this burial site? In a Monograph published by the Amity & Woodbridge Historical Society in November 2016, the Woodbridge Town Historian Marvin Aarons tells the tale:

"According to Woodbridge resident Edee Lockyer, who visited the cemetery as a child in the 1940s, the graves were then mounded up and covered with rocks. Sadly, the graves were repeatedly disturbed over many years. Today, there are no gravestones or burial mounds; rather, the grave sites are sunken."

From the various descriptions of the people last known to live at this settlement there are several about whom we might be able to learn more. For some clues, we can look back to 2003 when the Department of the Interior's Bureau of Indian Affairs released its decision against federal acknowledgement of the Golden Hill Paugussett Tribe. In a preliminary document related to this finding, on page 39, there's a section that seems to relate to this settlement:

The Mack Family Settlement: In the early 1830s, small pox virtually wiped out the small settlement in Woodbridge where Eunice Sherman Mack and her family had established themselves. The historical accounts of the Mack settlement are conflicting. One account purports that the selectmen of the town of Bethany (Incorporated in 1832), purchased a tract of land in what was then the town of Derby for a group of Indians called the “Macks” in 1832 (Molloy 1935, 394). However, Samuel Osbourne had purchased land for Eunice Mack in Woodbridge in 1802, a full 30 years prior to this reported “Bethany purchase,” and no record or deed explaining the sale or transfer of that land has been submitted. Accounts of the Macks generated after 1832, do show them living and owning property in Derby rather than Woodbridge.

In 1833, small pox was reported to have killed at least nine (unidentified) people in the household, of which Eunice Mack, her son James, and her daughter (or possibly a daughter-in-law) Ruby are known to have survived. Eunice Mack was recorded in the 1840 census in Derby with two other free people of color, one male and one female, both between the ages of 36 and 55; her death was recorded in 1841, in Woodbridge, in the same church where Eunice (then identified by her surname Mansfield) and two of her children were baptized in 1802. There is no further mention of Ruby Mack in conjunction with James Mack, but four years after the death of Eunice Mack, Samuel French was authorized by the General Assembly to sell the lands of “a certain pauper - an Indian, named James Mack - the owner of certain lands and other real estate in said town of Derby” (Petitioner 6/17/1994, Tab. 15). In 1849, a woman named Ruby Mack died in Derby, and she may have been a daughter of Eunice Mack. In 1850, James Mack, described as a 50 year old Black male born in Connecticut, was recorded in the New Haven County Poor House (U.S. Bureau of the Census 1850b). There is no other information regarding James Mack after 1850, or any other descendants of Eunice Sherman Mack/Mansfield.

Who was Eunice? Elsewhere in the 1935 "Tercentenary" publication, on page 342, an indigenous woman named Eunice who lived in this area and her connection as a grandchild of the Scattacook Chief Gideon Mawheu is described:

"The Indians sold land at various times, and by 1731, after the death of Cockapatana at Wesquantock, the town of Derby purchased from John Howd and other Indians all the remainder, "except the plain that lieth near the Falls up to the foot of the hill." A few years later, about 1740, an Indian named Joseph Mawheu settled at the Falls. He is said to have been a son of Gideon Mawheu, chief at Scattacook. He lived for a while with the Turkey Hill Indians, marrying an East Haven Indian who is recorded by the Reverend Daniel Humphreys as having been admitted into the Church of Christ in Derby on September 12, 1779. He calls her "Ann Chuse;" but in the Reverend Martin Tuller's record in 1784, "Joseph and Anna Mawheu" are both registered as members. The man was known as "Joe Chuse" because of his peculiar pronunciation of the word "choose;" and from about 1750 until after his departure to the Scattacook Reservation about 1780, Seymour was frequently called "Chusetown." Chuse or Mawheu served as a scout in the French and Indian Wars and in the Revolution. In 1812 the last of the Indian holdings at Promised Land were sold to General Humphreys and Mrs. Phoebe Stiles. Eunice Mawheu, daughter of Joe Chuse, died in Kent in 1859, at the age of one hundred four. Until a short time before her death she made frequent visits to Humphreysville."

So is the Eunice who lived at the settlement on Deerfield Lane related to this Eunice who's father Joe's nickname of 'Chuse' had been the origin of the name 'Chusetown' by which Naugatuck was known in colonial days before the Revolution? Was Joseph and Anna Mawheu's daughter Eunice really 104 when she died in 1859 (or 1860)? Or could her birth record instead be mixed up with the Eunice who lived on Deerfield Lane and was purported to have died in 1841?

Records in the Woodbridge Town Clerk's Office provide details: "Bill of Mortality for 1841... May 22 Eunice Mack colored woman, AE 85 Yrs." This would place her birth about 1756 — 104 years before the other Eunice's death date of 1859/60.

By visiting the Schaghticoke First Nations website we can learn more about the history of these Indigenous Peoples whose ancestral homelands extended throughout the Hudson and Harlem Valley regions of New York, as well as in Connecticut and Massachusetts. The website's timeline includes this intriguing mention of Eunice:

"New York historian Benson Lossing interviews Gideon Mauwee’s granddaughter Eunice Mauwee on the Schaghticoke reservation in 1859."

Could this be the "Mr. Lossing" that W.C. Sharpe mentions in the opening paragraphs of this post? Could this interview hold more clues for us? One thing is certain: more research is needed.