Jack Woolsey — from Long Island, to Connecticut, to the South China Sea

The Witness Stone Project connects Jack Woolsey to the household of Abraham Hillhouse and Rebecca Woolsey his second wife, who owned a farm in Woodbridge where the Country Club of Woodbridge later operated.

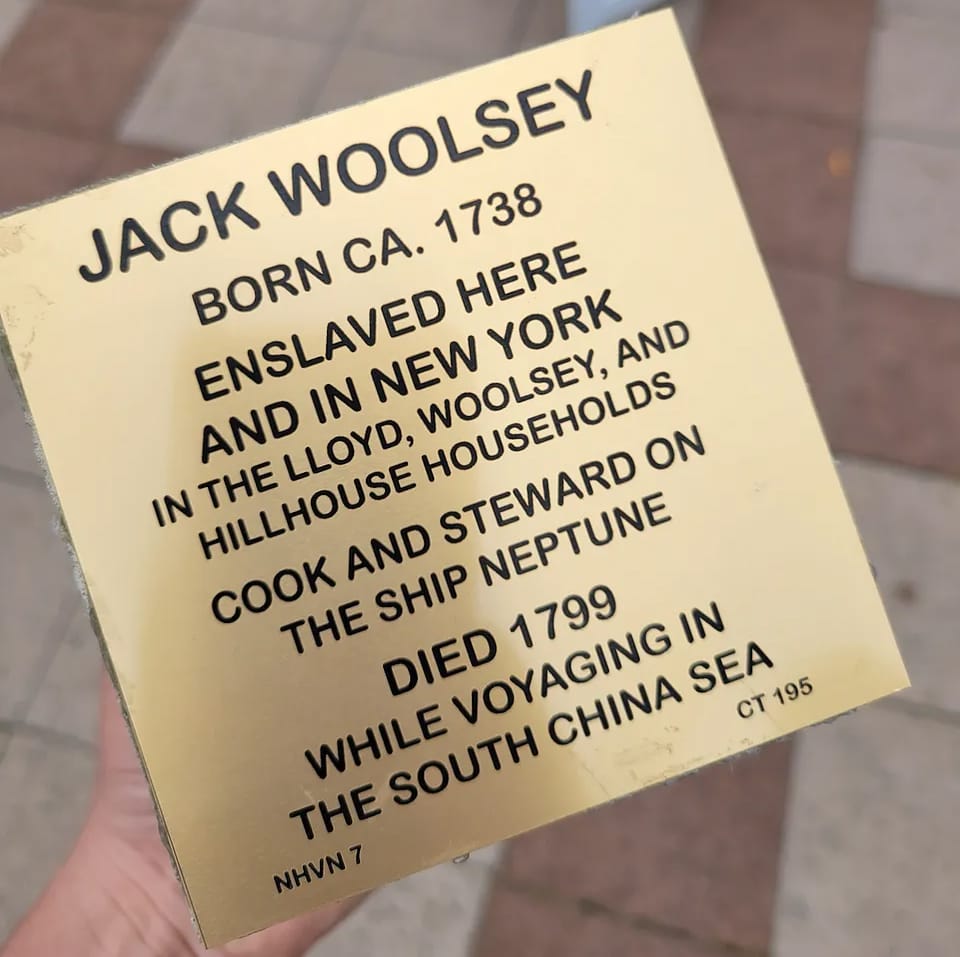

The New Haven Independent published a story last month about the dedication of a Witness Stone marker to honor Jack Woolsey, who was born about 1738 and enslaved in New Haven and New York in the Lloyd, Woolsey, and Hillhouse households. In 1796, he joined the crew of the ship Neptune as a cook and steward.

A few years ago, 'Today in Connecticut History' ran a feature story on this ship and its place in history: The Voyage of the Neptune Reaps Astonishing Wealth. But Jack Woolsey did not make it back to New Haven with the crew that arrived in July 1799 — a full 2 years and eight months after their departure. He died of dysentery while the ship was in the South China Sea on the voyage home.

The celebration of Jack Woolsey's life in 2024 was made possible by the work of students at New Haven's James Hillhouse High School who partnered with the Witness Stones Project, a local nonprofit organization that "seeks to restore the history and honor the humanity of enslaved individuals who helped build our communities. The project teaches students about the experience of enslavement in Connecticut and highlights an enslaved person from the community in which the students reside" through research and an analysis of primary documents uncovered by the students. Their description is as follows:

Jack Woolsey was sold at the age of 19 to Henry Lloyd in Long Island; Jack joined Lloyd’s daughter’s (Rebecca) and son-in-law’s (Melancthon Taylor Woolsey) household. When her husband died, Rebecca retained legal rights to Jack. Rebecca moved to New Haven and into her daughter’s and son-in-law’s, James Hillhouse, home where Jack continued to be enslaved by Rebecca. Jack joined the crew of the Neptune as a cook. Neptune sailed from New Haven in November 1796 to the Falkland Islands and then to China, where the crew traded seal skins for silks, teas and other items.

Jack Woolsey's full Witness Stone Project story can be read at the organization's website, where he is honored as CT marker #195. And what was his connection to the Hillhouse household in the greater New Haven area? For more clues about Jack's life, we can look for him in the recently published 'Yale and Slavery - A History,' a comprehensive accounting of the ties to enslavement that the university's archives illuminate. Indeed, Jack Woolsey appears on pages 104 and 105:

"In the same years that [U.S Senator James] Hillhouse built an illustrious career as a public servant, he enslaved other people, including children, and a number of enslaved people were part of his daily life. His first wife, Sarah Lloyd, came from the large landowning and slaveholding Lloyd family on Long Island, New York. She died along with her infant child in 1779. The poet Jupiter Hammon had been held in slavery by the Lloyd family and was living with the Hillhouses at the time of the Revolutionary War battle and Sarah’s travails. Hillhouse soon remarried, this time to Rebecca Woolsey, a double first cousin of his first wife. Rebecca’s grandfather, the Reverend Benjamin Woolsey, a member of the Yale class of 1707, left five enslaved people in his will when he died, specifying that these people—Primus, Hagar, Ishmael, Judith, and Candace—were to “be Sold and the Money Thence Arising to be . . . for the Use of my said Wife.” When Rebecca’s father, Colonel Melancthon Taylor Woolsey, died, the inventory of his estate in 1758 included enslaved Black men, women, and children named Ishmael, Saul, Prissila, Jack, and Patience.

...

Rebecca Hillhouse’s mother, Rebecca Woolsey, and her unmarried sister Theodosia moved from Long Island to live with Rebecca and James in New Haven after they married. Jack, one of these enslaved people, accompanied the Woolseys to New Haven. (This may have been the same Jack who, as a boy, appeared in her husband’s will some thirty years earlier.) In 1784, Mrs. Woolsey, James’s mother-in-law, wrote of her great distress that Jack had to endure a major, costly medical surgery and lamented her son’s fi- nancial woes. She declared herself “as poor as a church mous” and complained of having to pay for Jack’s operation—this, after listing her supply of satin bed linens and many other fine items of clothing. Jack recovered and continued to wait on Mrs. Woolsey."

The voyage of the ship Neptune on which Jack Wooley's life ended, is also the subject of extensive historical research, including artifacts and records in the collection of the New Haven Colony Historical Society, now the New Haven Museum.

Included in the listing of the Society's Manuscripts Library, Maritime Collection, in Box I, contained in folders I and J (pg. 3 of the listing) are the Neptune's papers, extracts from the journals of Elijah Davis (1777-1853), and a transcript of the diary of David Forbes (1775-1809) – while the original, bound and wrapped diary is also in the collection, labeled folder L. Further, in Box II, folder A-2 (pg 4) includes biographical data on the Neptune's Captain Daniel Greene (1765-1817) who was later Lost at Sea, and the diary of Ebenezer Townsend, Jr. (1742-1824) who was the namesake son of the ship's owner and the individual who worked as the Neptune's 'supercargo' a job that entailed managing the cargo owner's trade, selling the merchandise in ports to which the vessel was sailing, and buying and receiving goods to be carried on the return voyage.

Ebenezer also offers a fascinating glimpse of the Neptune's voyage in letters to his brother describing each month of the long journey — these were collected and presented in the Papers of the New Haven Colony Historical Society, Vol. IV published in 1888 (pages 1-115). On its voyage circumnavigating the globe, the Neptune was the first New Haven-built ship to sail into the Pacific Ocean as it rounded the southernmost tip of South America, and it also made stops in Cape Verde, the Falkland Islands, and the islands that would become the state of Hawaii some 160 years later.

More details of the Neptune's voyage are captured in a New York Times story “On the Neptune, Three Years Under Sail” published in 1997 as the bicentennial of the trip was being celebrated with an exhibition based on first-hand accounts written by members of the crew. Included in the show were “paintings and engravings, maps and atlases, luxury goods brought back from Asia and dozens of period artifacts.”

“It was rare to circumnavigate the world in that day,” said Amy L. Trout, the exhibition's curator and designer who spent more than a year on the research alone. “It needed a good ship, good crew and an experienced captain.”

En route to China, the Neptune made a stop in the Sandwich Islands. By that time, the lack of fresh fruit was beginning to take a toll on the men's health. “A number began to complain of the scurvy at that time, which increased, and on our arrival at Owyhee several were black to their hips with it,” reads the diary of Ebenezer Townsend. “We were fearful of losing some, but they got well astonishingly almost immediately on our arrival. We are now all in good health.”

The crew of 36 included experienced sailors and raw hands, whites and blacks, carpenters, cooks, stewards, cabin boys and Dr. David Forbes, age 21, who set bones, made salves and herbal teas and, in his diary, complained frequently of being sick.

Who was this David Forbes? New Haven was a relatively small community in the 1790s. In January 1784, after the Revolution has ended and the Charter of the City of New Haven is signed by the Governor of Connecticut, “the inhabitants were estimated at 7,960 souls; of whom 3,350, less than almost any one of our wards to-day, were in that part which was chartered as a city,” according to a historic account published by the New Haven Colony Historical Society in 1884. The process by which the city of New Haven was established also saw its outlying communities leaving to form towns of their own – such as Woodbridge, also incorporated in 1784. But despite this geographic distance now codified on a municipal level, the community remains connected and many of the people living in the greater New Haven-area are related by marriage or blood. For example, the above mentioned 21 year-old David Forbes was a first cousin of Sarah 'Sally' Forbes (1767-1818), as David and Sarah's fathers were brothers. She came to live in Woodbridge when she married Jeremiah Beecher (1764-1826) in 1800 as his second wife. The couple are buried in Eastside Cemetery on Pease Road.

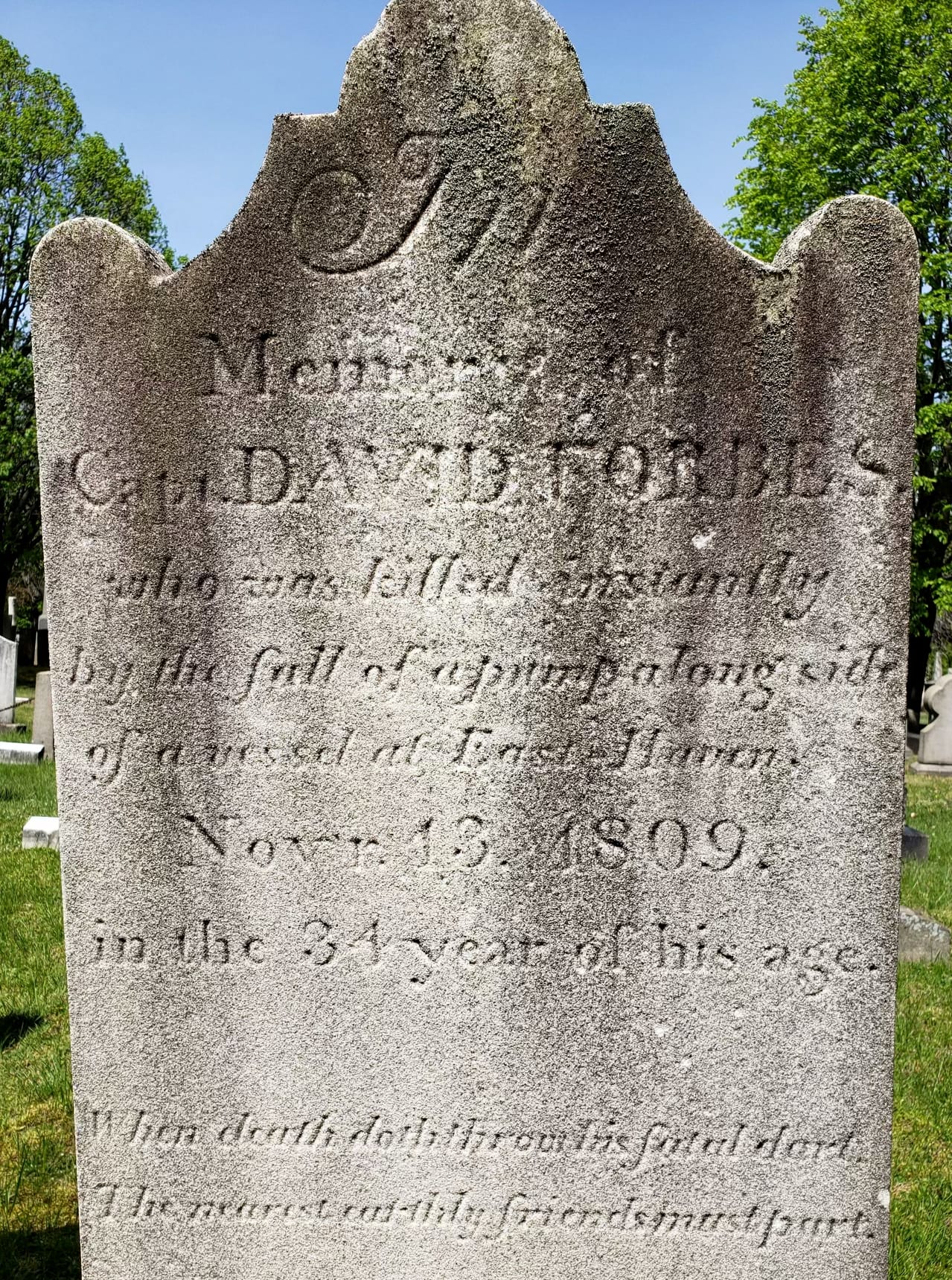

After the Neptune's return to Connecticut, David Forbes, who eventually becomes a Captain himself, settles back in his hometown of East Haven. His gravestone inscription there tells the tale of his untimely end just a decade later, and reminds us of the finality of all earthly journeys:

In Memory of

Capt. DAVID FORBES

who was killed instantly

by the fall of a pump along side

of a vessel at East Haven

Nov'r 13, 1809

in the 34 year of his age

When death doth throw his fatal dart

The nearest earthly friends must part