Hillhouse and Woodbridge family connections

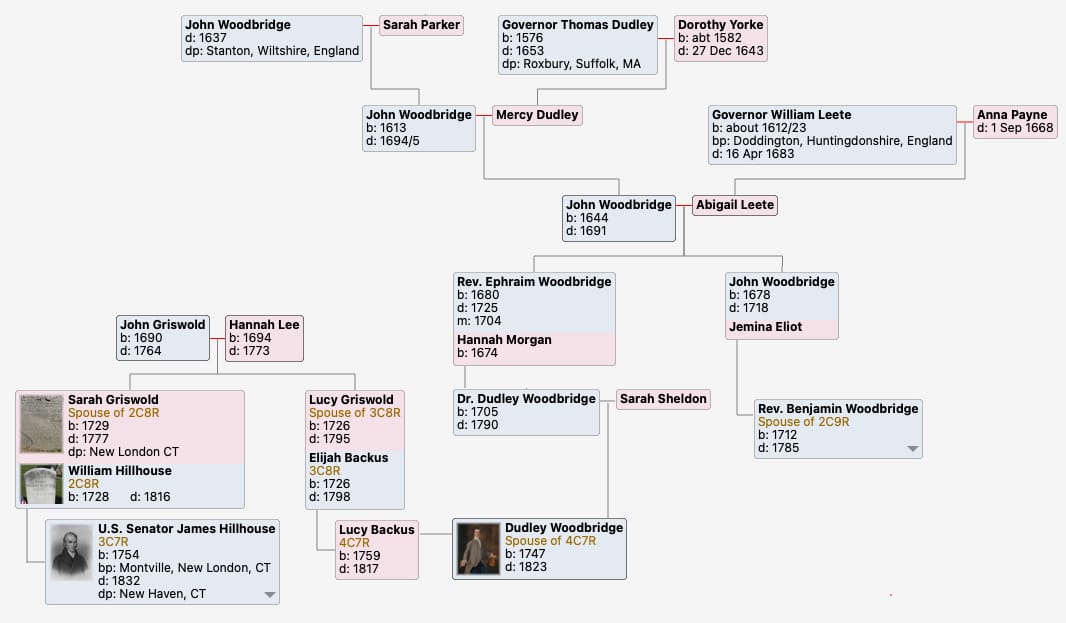

The family of James Hillhouse (1754-1832) is not only connected to the town of Woodbridge by virtue of the property he owned here, but also by the marriage of his first cousin to the son of a first cousin of the Reverend Benjamin Woodbridge (1712-1785) for whom the town was named in 1784. Let's map out how these branches of their family trees are joined.

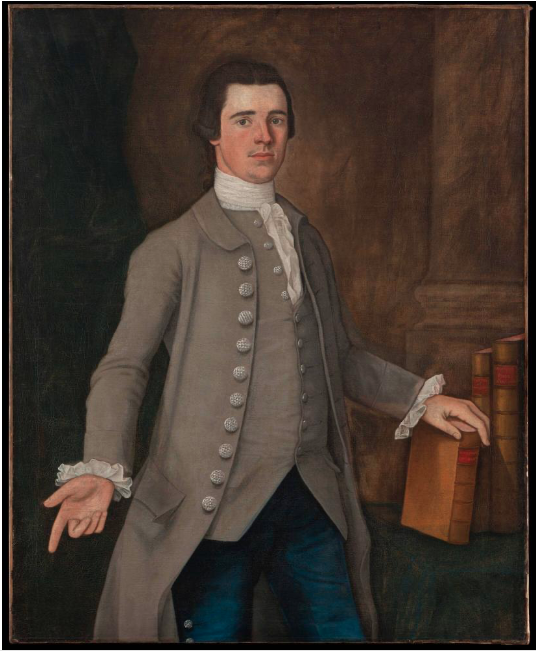

On his mother's Griswold side, James Hillhouse's first cousin was Lucy Backus (1759-1817) whose mother Lucy was a sister of James' mother Sarah. In 1774, Lucy Backus married Dudley Woodbridge (1747-1823) who graduated from Yale with the class of 1766 and shortly thereafter had his likeness painted by the well known portraitist John Durand. The canvas is now part of the collection at Colonial Williamsburg where its description reads:

Bachelor and Connecticut resident, Dudley Woodbridge, a recent graduate of Yale University, had just reached his majority when this portrait was painted, about 1768. He would go on to enjoy careers in several fields, including law and overseas trade, and he was the first postmaster of Norwich, Connecticut. Woodbridge moved to Ohio before the end of the eighteenth century and spent the rest of his life there.

His father, Dr. Dudley Woodbridge (1705-1790), was a first cousin of Reverend Benjamin Woodbridge who himself graduated from Yale in 1740 and became the first pastor of Amity Parish just two years later. Benjamin's father, Reverend John Woodbridge (1673-1718) was the first minister of West Springfield, Massachusetts while John's younger brother the Reverend Ephraim Woodbridge (1680-1725) served as the first pastor of the church in Groton, Connecticut where his son Dudley — Benjamin's first cousin — would establish his medical practice.

The doctor's namesake son remains in Connecticut for a short time after serving in the Revolutionary War and he and Lucy have at least five children here before leaving for the frontier territory of Ohio as noted in the description of Dudley's portrait, sometime before July 1794. In 1795 we pick up another thread of this couple's story in the book 'Yale and Slavery - A History,' as Lucy's cousin James Hillhouse receives a letter that connects the couple to two children enslaved by Hillhouse: a girl named Hagar, who was born March 17, 1786, and a boy named Jupiter born on June 22, 1789.

“Hagar died [July 23, 1794] at the age of nine, and like her biblical namesake... she died a slave. Her brother, the little boy named Jupiter, outlived Hagar, but only to endure other trials of slavery, separation, and hardship. In 1795, the boy’s mother, Judith Cocks, wrote Hillhouse, bereft and confused. Cocks and her son had been taken to Marietta, Ohio, by Hillhouse’s first cousin, Lucy Backus Woodbridge and her husband, Dudley Woodbridge (Yale 1766). (This fact alone suggests a disregard for the law, since it was illegal to transport enslaved people outside the state.)

Cocks told Hillhouse that Mrs. Woodbridge and her sons “thump and beat [Jupiter] as if he was a Dog” and begged for clarity about Jupiter’s status. Telling Hillhouse she was living in a “strange country without one friend,” she asked him to “be so kind as to write me how Long Jupiter is to remain with them.” Woodbridge had told Cocks that Jupiter “is to live with her untill he is twenty five years of age this is something that I had no idea of I all ways thought that he was to return with me to new England.” Cocks further implored Hillhouse not to sell her boy to Mrs. Woodbridge. Even more wrenching, she mentions her daughter Hagar, apparently unaware that the girl had died the year before.

In this rare document, an enslaved mother speaks directly to one of the most powerful men in the country about her fears and, in doing so, articulates the grief, frustration, and sense of powerlessness many enslaved parents must have felt. Un- able to navigate the gradual abolition law with any certainty or genuine hope, Cocks was trying as best she could to protect her children from the violence and cruelty of slavery, appealing to Hillhouse’s sense of humanity to spare her son.

... Young Jupiter’s fate is unknown, but slavery continued in the Woodbridge household. For although since 1787 the Northwest Ordinance had prohibited both slavery and indentured servitude in the territory, which included Ohio, Lucy Woodbridge declared in a letter to a friend a few years later, in November 1802, “I have bought a good natured Negro boy who has five Years to serve.”

Dudley and Lucy Woodbridge had at least three sons who lived with them in Ohio, including William Woodbridge (1780-1861), who later settled in Michigan and was the second Governor of Michigan from 1840 to 1841 after which he was elected to the United States Senate, where he served from 1841 to 1847.

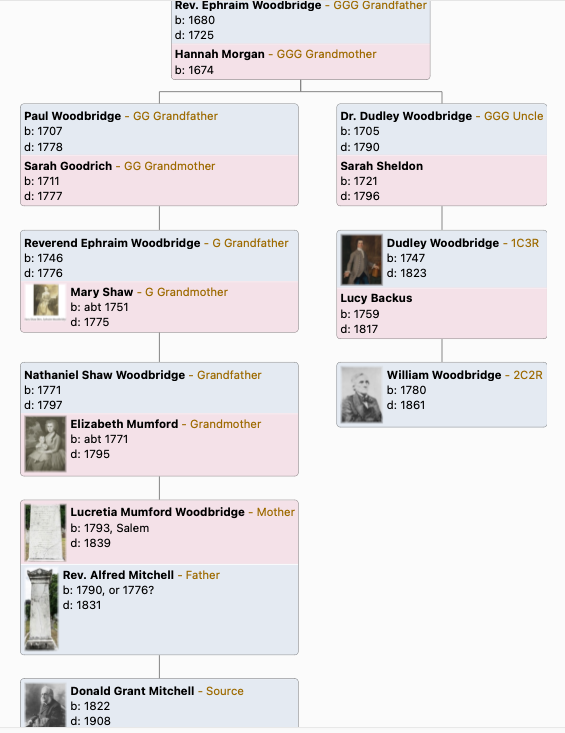

In 1841, at the time William was serving as Governor in Michigan, a relation of his father's back in Connecticut is graduating as the valedictorian of his class at Yale. William's grandfather, Dr. Dudley Woodbridge, had a brother two-years his junior named Paul Woodbridge (1707-1778) and Paul's great-great-grandson is just setting out in life as he graduates from Yale where he studied law but would soon take up literary pursuits, to much acclaim.

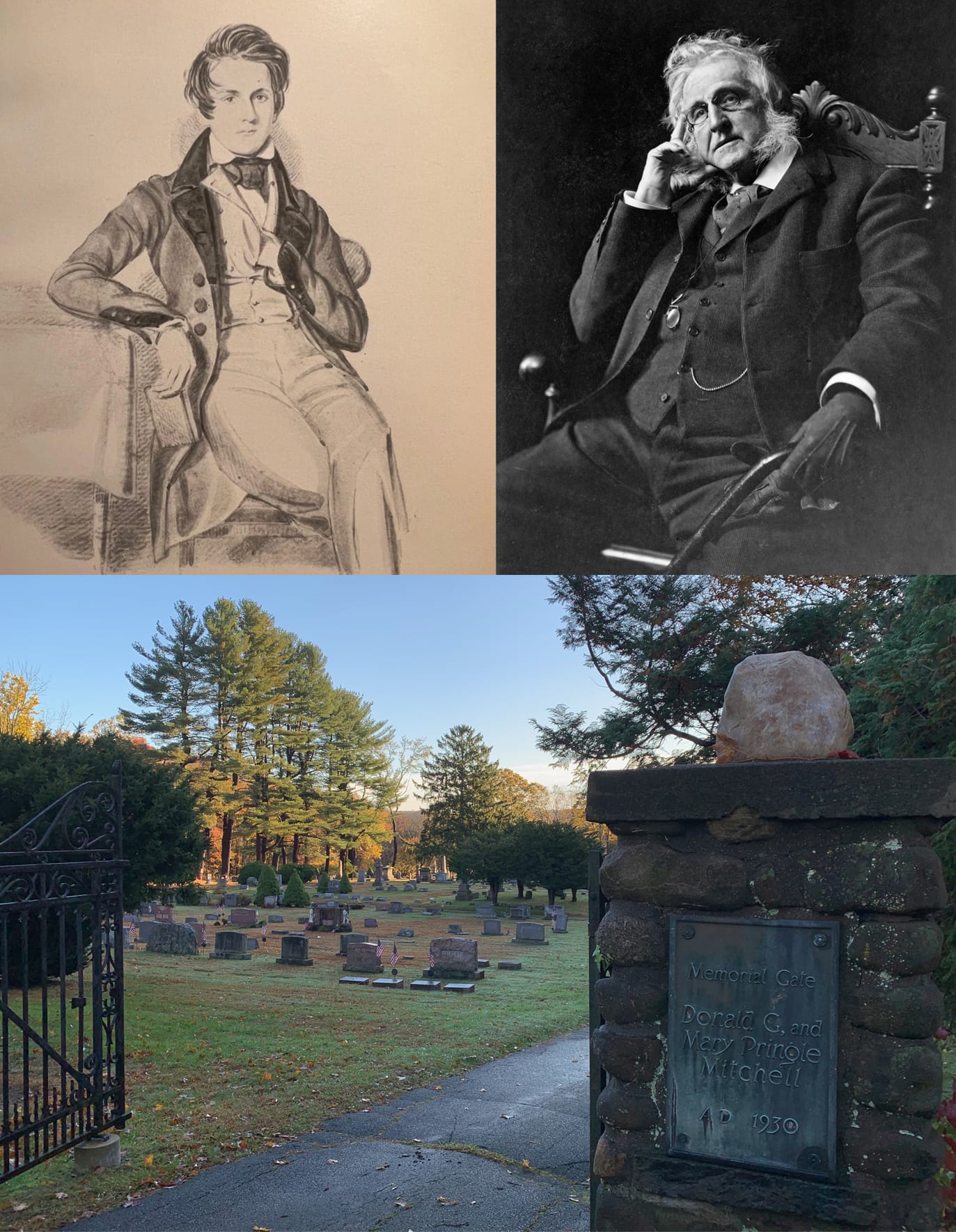

Donald Grant Mitchell (1822-1908), the essayist and novelist who wrote under the pen name Ik Marvel and also made significant contributions as the architect of much of the New Haven's original park system, is related to the Woodbridge clan through his mother Lucretia Mumford Woodbridge (1793-1839), who was a daughter of Paul's grandson Nathaniel Shaw Woodbridge (1771-1797) – making her Governor William Woodbridge's 2nd cousin, once removed. Donald would go on to provide another minor connection between the Woodbridge family and the town of Woodbridge, when at the close of his illustrious career he is laid to rest alongside his immediate family members in the town's Eastside Cemetery. The wrought iron entry gate of the cemetery is a gift from his family dedicated to his memory.