Sarah Cowell – the Sperry descendant who ran away with a pirate

At times, distant minds seem to converge upon the same star-lit idea, illuminating a shared path of thinking. Do distant cousins somehow share a connection that lures them to embark down parallel paths of thinking, tracing our steps through the woods of family stories passed down to us, to arrive in the same clearing to greet each other again?

Earlier this week, I had been looking up Captain John Beecher in my genealogy research notes, tracing his descendants and connections in town. Captain Beecher is a notable figure in Woodbridge history, and I intend to write more about him in a future essay. But for now, as I followed the threads of his family’s story, I was reminded of his connection to the Downs and Cowell families, whose homesteads stood just down the road from Captain Beecher’s former farm — the present-day CCW property (the subject of a previous essay).

Thinking about these families, I recalled a story of intrigue and mystery involving a farmer’s daughter here in old Woodbridge eloping with a so-called pirate. And then, as if on cue, my cousin Priscilla Linville called me out of the blue. As soon as our conversation began, I realized she was talking about this very same family. What a remarkable coincidence! After our conversation, Priscilla sent me a follow-up email and attached the copy of the news clipping she had in her collection of family treasures.

With such serendipitous timing, it felt like the stars had just aligned and this was indeed the week to convey Sarah Cowell’s story to you, dear readers.

In the early 19th century, as a young woman from Woodbridge, Sarah Cowell shocked her family and community when she vanished on a trip to New Haven, only to "reappear" years later in a most unexpected way. Sarah's story — a tale of romance, adventure, and scandal — has been passed down through generations.

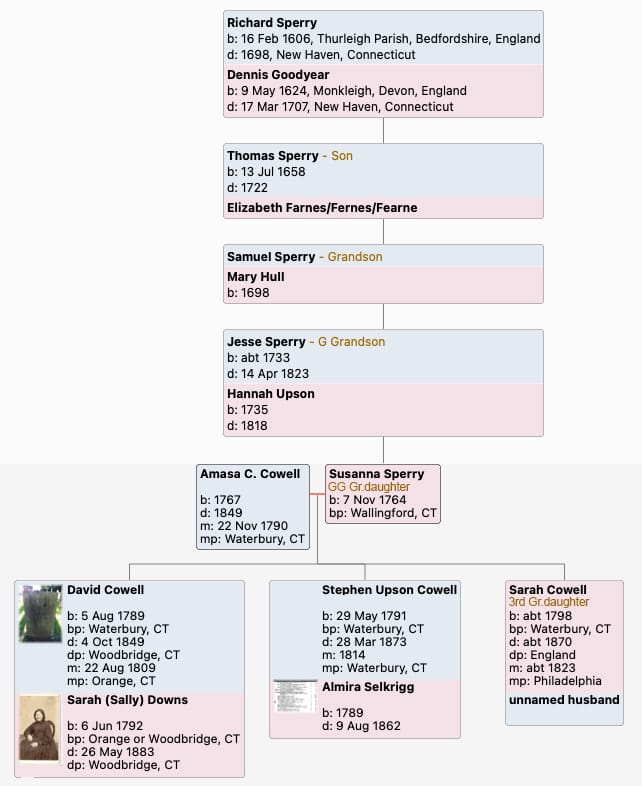

Sarah was born into a family with deep roots in Woodbridge. She and her siblings David Cowell (1789-1809) and Stephen Cowell (1791-1873) were the children of Amassa Cowell (1767-1849) and Susanna Sperry (born in 1764). Susanna was a daughter of Jesse Sperry (1733-1823) and Hannah Upson (1735 – 1818) and on Jesse’s side of the family Sarah and her brothers could trace their Sperry line back to their 3rd great-grandparents Richard and Dennis Sperry.

According to family accounts and the old news clipping Priscilla shared, Sarah apparently met a ship captain during one of the family's weekly visits to New Haven. The captain, reportedly involved in trade between Jamaica and New England, had a reputation in business that was both lucrative and shadowed by whispers of smuggling. Whether driven by love, adventure, or rebellion, one day Sarah abruptly ran away with him, leaving behind her life in Woodbridge.

For years, her whereabouts remained a mystery. Then, an image of Sarah dramatically surfaced — a large wooden crate arrived from England containing an oil painting of a poised woman adorned in elegant attire. The painting, said to have been sent by Sarah herself, showed her looking every bit the lady of a grand house, "arrayed in the finest laces and headgear, and oriental topaz earrings." This was confirmation of what her family had long feared: Sarah had not only left them, she had fully embraced a life far removed from their rural existence. "Her posture, poise and refinement suggested that of a lady, a long way from a humble girl on a farm."

Although she looked much more refined than they remembered her from years earlier, she was instantly recognizable to her former neighbors in Woodbridge who saw the portrait. It was believed that after running away, she had eloped with her sea captain and went on to live in comfort and wealth somewhere in England, far from the simple life she had known in Woodbridge.

However, the reaction from Sarah’s family was not one of acceptance. The Cowells were scandalized by Sarah's decision, and had refused to read her previous letters, destroying them unopened. Generations of the family apparently could not bring themselves to accept her departure from Woodbridge to pursue a new life. Rather than displaying her portrait with pride, they turned it to face the wall,"as if it were a microbe of a new plague." Even decades later, when the portrait was rediscovered in 1908, an elderly family member reportedly reacted passionately.

With white-hot indignation, she cried, “Don’t fetch it around me! I never want to see it again! ”

While Sarah’s family dismissed the captain as a pirate, the exact nature of their objection remains uncertain. His trade between Jamaica and New Haven likely involved the transport of rum and molasses — highly profitable goods that formed a significant part of the economy at this time. Some merchants engaged in this trade legally, while others smuggled goods to evade taxation. However, the deeper concern may have been moral rather than legal. The rum and molasses trade was deeply intertwined with what was known as triangular trade, and relied on the labor of enslaved people in the Caribbean. Did her parents reject Sarah's sea captain simply because he was said to have engaged in illicit rum-running, or did they fear his ties to the broader system of slavery that sustained the sugar and rum industries? This ambiguity remains, leaving open the question of whether their scorn was about legality or ethics — or both.

The Cowell family's story is closely tied to 51 Beecher Road, a historic house in Woodbridge that remained in the possession of the Downs family – Sarah’s extended family members – well into the 20th century. As described on page 46 of the Historic Woodbridge book, this house was built for Shelden Downs (1790–1856), with the help of his father Joseph Downs and was passed through generations of his descendants. Shelden’s daughter, Emily, married David Burnham and later took in boarders at this house after separating from her second husband, Edson Sturges of Norwalk.

The Shelden Downs house remained in family hands, eventually inherited by Emily’s daughter, Alice Burnham, who became a nurse. This home is also remembered for housing a tea room known as the “Blue Jay Tea Room,” named for the birds painted on its walls in the early 20th century.

In 1907, Emily’s cousin’s wife, Annie Davis Cowell (born 1845), moved into the house after selling the Cowell farmhouse, which had stood roughly across Rimmon Road (approximately between today's 85 and 89 Rimmon Road). When the new owners of the farmhouse discovered Sarah’s portrait in the attic and attempted to return it, Annie Cowell refused to take it back, reinforcing the family's enduring rejection of Sarah’s story. Here is the full text of the news article with many additional details:

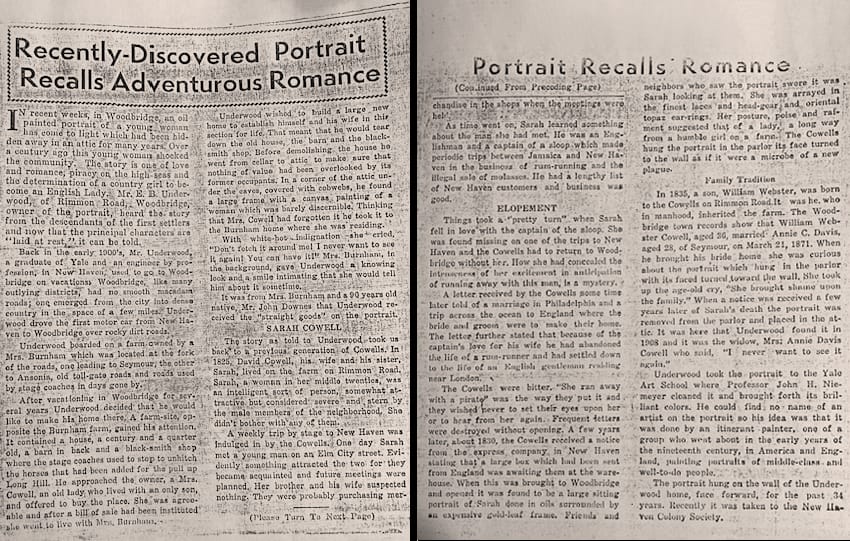

Recently-Discovered Portrait Recalls Adventurous Romance

In recent weeks, in Woodbridge, an oil-painted portrait of a young woman has come to light which had been hidden away in an attic for many years. Over a century ago, this young woman shocked the community. The story is one of love and romance, piracy on the high seas, and the determination of a country girl to become an English Lady. Mr. E.B. Underwood, of Rimmon Road, Woodbridge, owner of the portrait, heard the story from the descendants of the first settlers and now that the principal characters are “laid at rest,” it can be told.

Back in the early 1900s, Mr. Underwood, a graduate of Yale and an engineer by profession in New Haven, used to go to Woodbridge on vacations. Woodbridge, like many outlying districts, had no smooth macadam roads; one emerged from the city into dense country in the space of a few miles. Underwood drove the first motor car from New Haven to Woodbridge over rocky dirt roads.

Underwood boarded on a farm owned by a Mrs. Burnham, which was located at the fork of the roads, one leading to Seymour, the other to Ansonia, old toll-gate roads and roads used by stagecoaches in days gone by.

After vacationing in Woodbridge for several years, Underwood decided that he would like to make his home there. A farm-site opposite the Burnham farm gained his attention. It contained a house a century and a quarter old, a barn in back and a blacksmith shop where the stagecoaches used to stop to unhitch the horses that had been added for the pull up Long Hill. He approached the owner, a Mrs. Cowell, an old lady who lived with an only son, and offered to buy the place. She was agreeable and after a bill of sale had been instituted she went to live with Mrs. Burnham.

Underwood wished to build a large new home to establish himself and his wife in this section for life. That meant he would tear down the old house, the barn and the blacksmith shop. Before demolishing the house he went from cellar to attic to make sure that nothing of value had been overlooked by its former occupants. In a corner of the attic under the eaves, covered with cobwebs, he found a large frame with a canvas painting of a woman which was barely discernible. Thinking that Mrs. Cowell had forgotten it, he took it to the Burnham home where she was residing.

With white-hot indignation, she cried, “Don’t fetch it around me! I never want to see it again! You can have it.” Mrs. Burnham, in the background, gave Underwood a knowing look and a smile intimating that she would tell him about it sometime.

It was from Mrs. Burnham and a 90-year-old native, Mr. John Downes that Underwood received “the straight goods” on the portrait.

SARAH COWELL

The story as told to Underwood, took us back to a previous generation of Cowells. In 1825, David Cowell, his wife, and his sister, Sarah, lived on the farm on Rimmon Road. Sarah, a woman in her middle twenties, was an intelligent sort of person, somewhat attractive but considered severe and stern by the male members of the neighborhood. She didn’t bother with any of them.

A weekly trip by stage to New Haven was indulged in by the Cowells. One day Sarah met a young man on an Elm City street. Evidently something attracted the two, for they became acquainted and future meetings were planned. Her brother and his wife suspected nothing. They were probably purchasing merchandise in the shops when the meetings were held.

As time went on, Sarah learned something about the man she had met. He was an Englishman and a captain of a sloop, which made periodic trips between Jamaica and New Haven in the business of rum-running and the illegal sale of molasses. He had a lengthy list of New Haven customers, and business was good.

ELOPEMENT

Things took a “pretty turn” when Sarah fell in love with the captain of the sloop. She was found missing on one of the trips to New Haven and the Cowells had to return to Woodbridge without her. How she had concealed the intenseness of her excitement and anticipation of running away with this man is a mystery.

A letter received by the Cowells sometime later told of a marriage in Philadelphia and a trip across the ocean to England where the bride and groom were to make their home. The letter further stated that because of the captain’s love for his wife he had abandoned the life of a rum-runner and had settled down to live the life of an English gentleman residing near London.

The Cowells were bitter. “She ran away with a pirate,” was the way they put it, and they wished never to set eyes upon her or to hear from her again. Frequent letters were destroyed without opening. A few years later, about 1830, the Cowells received a notice from the express company in New Haven stating that a large box had been sent from England and was awaiting them at the warehouse. When this was brought to Woodbridge and opened it was found to be a large sitting portrait of Sarah done in oils and surrounded by an expensive gold leaf frame. Friends and neighbors who saw the portrait swore it was Sarah looking at them. She was arrayed in the finest laces and headgear and wore oriental topaz earrings. Her posture, poise and refinement suggested that of a lady, a long way from a humble girl on a farm. The Cowells hung the portrait in the parlor its face turned to the wall as if it were a microbe of a new plague.

FAMILY TRADITION

In 1835, a son, William Webster, was born to the Cowells on Rimmon Road. It was he who, in manhood, inherited the farm. The Woodbridge town records show that William Webster Cowell, aged 36, married Annie C. Davis, age 28, of Seymour, on March 21, 1871. When he brought his bride home, she was curious about the portrait which hung in the parlor with its face turned toward the wall. She took up the age-old cry: “She brought shame upon the family.” When notice was received a few years later of Sarah’s death, the portrait was removed from the parlor and placed in the attic. It was here that Underwood found it in 1908 and it was the widow, Mrs. Ann Davis Cowell, who said, “I never want to see it again.”

Underwood took the portrait to the Yale Art School, where Professor John H. Niemeyer cleaned it and brought forth its brilliant colors. He could find no name of an artist on the portrait so his idea was that it was done by an itinerant painter, one of a group who went about in the early years of the nineteenth century, in America and England, painting portraits of middle-class and well-to-do people.

The portrait hung on the wall of the Underwood home, face forward, for the past 34 years. Recently, it was taken to the New Haven Colony Society.

Sarah Cowell’s story is certainly one of intrigue, with hints of defiance and the eternal human draw to the unknown. What exactly became of her remains a mystery, but her tale endures — a reminder of the risks some take for love, freedom, or fortune.

If you have heard family stories about Sarah Cowell, know the whereabouts of the original oil painting, or have insights into her family connections in Woodbridge, please contact me if you would like to share them.